Growth is unsustainable. To compensate for the GHGs coming from the boom in air travel among Quebecers, the equivalent of two public transport projects like the REM would have to be built… every year.

Posted at 2:30 a.m.

Updated at 6:15 a.m.

The comparison is striking in the context where governments are sinking billions into the development of public transport – which goes without saying – while the effects of the boom in air flights go under the radar.

International air flights, it should be noted, are not included in the countries’ national greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory report (the NIR), unlike domestic flights.

One of the reasons: it is difficult to separate the GHGs of international flights between residents and tourists. Who is responsible for GHG emissions from planes taking off and landing in Dorval?

No clear accounting and therefore no accountability, no pricing and no debate.

Now, thanks to Statistics Canada, among others, I managed to estimate this resident-tourist split for Canada. Thus, we can reasonably calculate that two-thirds of the kerosene burned by Canada’s international flights is attributable to Canadian travelers and one-third to tourists. The figures are similar for Quebec1.

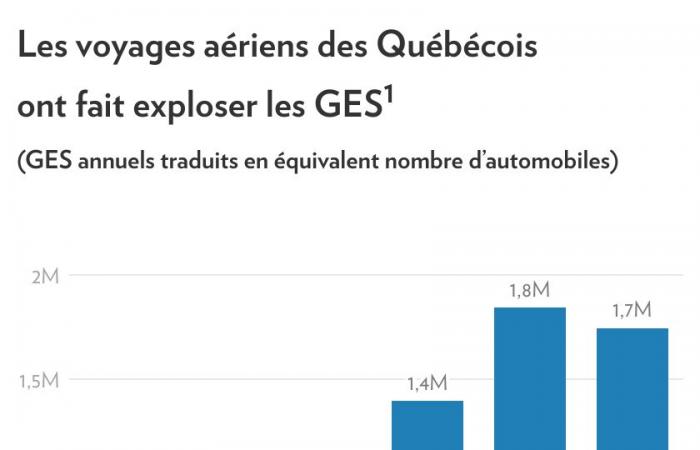

Result ? The air GHGs of Quebec travelers represent the equivalent of 1.8 million cars on our roads. This calculation includes GHGs from round-trip international travel (4.9 million tonnes) and those from domestic flights (900,000 tonnes).

Growth is exponential. Since 1990 – the reference year for our reduction targets by 2030 – GHGs from Quebecers’ travel abroad have tripled. When compared to automobile equivalents, the increase is greater, since over the same period, vehicles on our roads have become much more efficient. A chart is worth a thousand words.

The years 2020 to 2022 have reduced this air travel, given the pandemic context. But in 2023, travel has started again.

The number of trips by Quebecers abroad in 2023 thus exceeded the record year 2019 by 9%, with 4.7 million trips. Note that a person who takes two trips in a year represents two travelers in this calculation.

And the REM in all this? I arrive there.

The vast majority of environmentalists agree: to reduce our GHGs, we must develop public transport, make urban landscapes denser and thus reduce our dependence on cars. And I share this opinion, for the most part.

This is what we did with the REM project of the Caisse de dépôt et placement, the bill for which is around 8 billion. And that’s what we want to do with the Quebec mobility plan (tramway and others), which could cost 15.5 billion, and with the tramway for the east of the island of Montreal, 18.6 billion .

Reducing GHGs is not the only goal of these projects, we agree. They are designed to improve mobility, particularly for people with low incomes, and to better develop the economy. And they are part of an overall environmental plan. Nevertheless, the GHG argument linked to each project is central.

Now, two engineering firms have estimated the GHGs that could be saved with the REM. Their reports are public.

The Hatch firm has calculated that the REM will reduce GHGs by approximately 35,000 tonnes for its first year of operation.2. The Systra firm, for its part, achieves 98,613 tonnes of GHG savings each year, essentially thanks to “the modal shift from cars to REM3 “.

In short, it is a significant recurring reduction in GHGs, which represents between 11,000 and 32,000 fewer cars on our roads in the long term.

But do the mathas the Americans say: Quebecers’ trips added the equivalent of 1.3 million cars between 1990 and 2019. It is therefore the equivalent of 45,000 more cars that were added to our roads each year with these flights.

In other words, the explosion in travel by Quebecers has caused GHGs to increase approximately twice as fast, each year that a project like the REM has failed to reduce them.

It would therefore have been necessary, since 1990, to build the equivalent of two REM projects to compensate for our trips… per year.

The comparison may seem crazy, but it illustrates the extent of the impact of thefts. It assumes, of course, that the annual increase in flights is permanent, which is less certain than the permanence of projects like the REM, once built. But at the rate things are going, there is no indication that the volume of flights will decline, on the contrary.

As a general rule, defenders of air transport repeat that GHGs from this mode of transport only represent 1 to 2% of the world total. Or that biofuels will eventually power the Boeing and Airbus aircraft of this world. Or that it is business travel that is responsible, not our personal leisure travel.

First, business and conference travel represents less than 10% of total travel in Canada, according to Statistics Canada data.

Then, biofuels cannot be produced in sufficient volumes and, above all, they cost three to four times more than kerosene. We don’t see the day when the bill will drop and this fuel will replace kerosene, any more than hydrogen for that matter.

Finally, for the proportion of 1 to 2% of the global total that air GHGs represent, this portrait includes populous and poor countries, which use air transport relatively little.

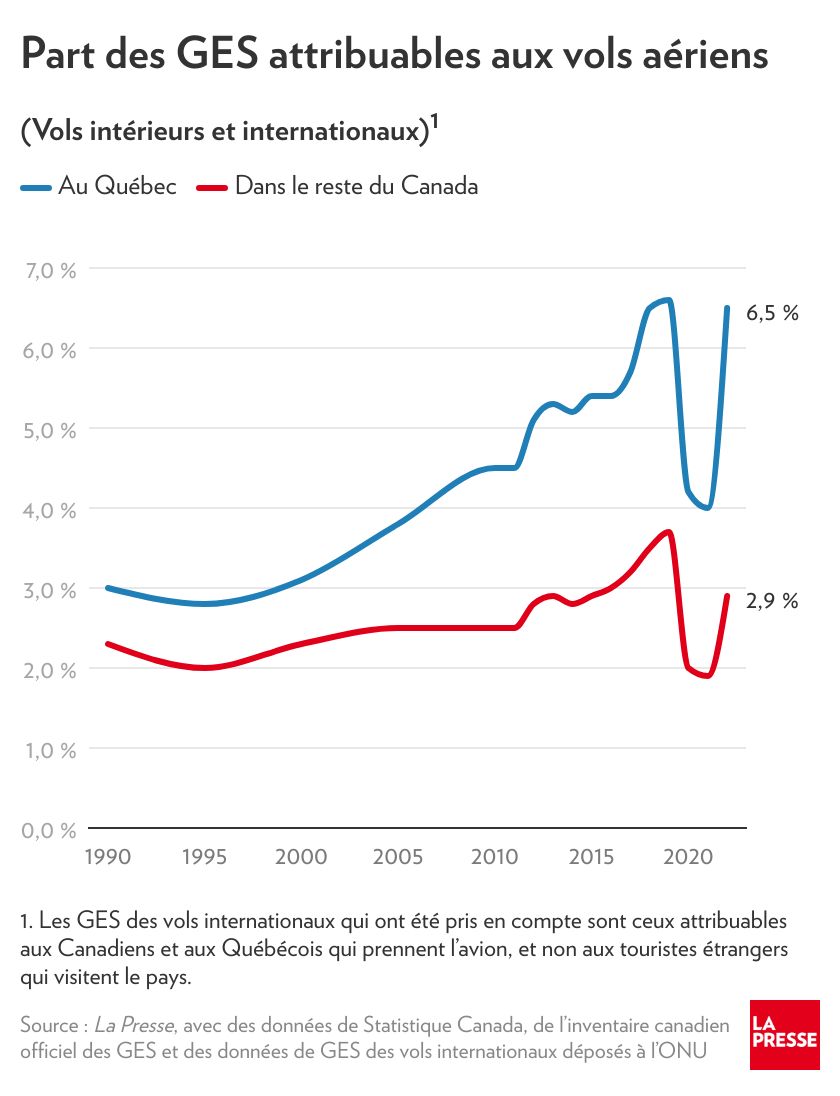

In Quebec and Canada, the proportion of GHGs linked to air flights is much greater. According to my estimates, it represents 6.6% of total GHGs in Quebec (in 2019) and 3.7% in the rest of Canada.4.

Quebec has a larger share because its total GHGs (the denominator) are lower, thanks to hydroelectricity, in particular. The fact remains that this share is growing much more here than in the rest of Canada (ROC).

In Quebec, it increased from 3% of total GHGs in 1990 to 6.6% in 2019, the last year available excluding the pandemic. A chart is worth a thousand words, have I said that before?

Another measure of growth: air GHGs represented 16% of those of passenger vehicles in 1990 in Quebec, but 31% in 2022. In the ROC, this proportion increased from 23% to 31% for the same period.

In short, we have huge debates about the billions to invest in public transportation, but the impact of our escapades on GHGs goes under the radar. Yet it would be so simple to moderate our air transport, to space it out, for example.

Yes, but aren’t we exemplary compared to other rich countries, like the United States, France or Japan? I will come back to this in detail on Wednesday.

Many thanks for their valuable advice and information to Jean-François Boucher, professor of ecology at UQAC, Cindy Gagné, manager of special projects at Statistics Canada, and Pierre-Olivier Pineau, professor specializing in energy at HEC Montréal.

1. In addition to Statistics Canada data on international travelers and residents entering or returning to Canada (24-10-0054-01), I made estimates using data on GHGs emitted by kerosene from international flights that declare the main countries in an Excel sub-file at the UN. Quebec travelers were allocated a larger share of Canadian GHGs than their proportion of Canadian travelers, because the distance of their flights is greater (71% of trips are outside the United States compared to 48% for the Canadian average).

2. Consult the study on greenhouse gases linked to the REM from the firm Hatch

3. Consult the report “Greenhouse gas emissions from the REM, operation phase” from the firm Systra

4. To do the calculation, I added to the total GHGs in the official inventory those that I estimated for international air transport. The share of air transport is the sum of GHGs from international and domestic flights divided by this denominator.