– The Unterlinden and local painting from the 15th century

The route goes from Basel to Strasbourg. Sets are reconstituted. The visit continues in the museum, located in an abbey.

Published today at 10:40 a.m.

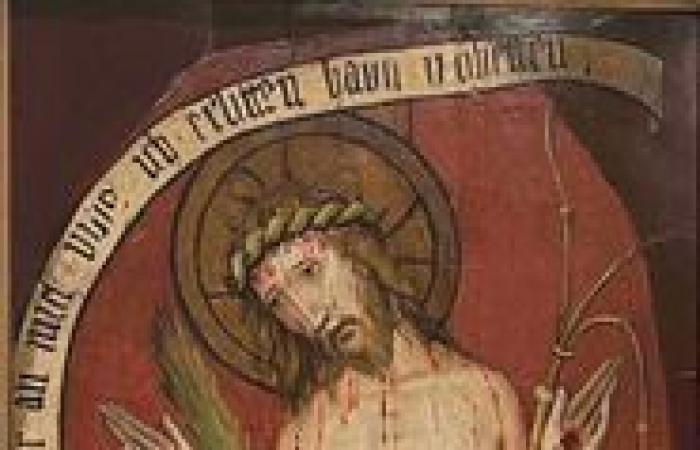

A man of sorrows from the 1420s. The work of course remains anonymous.

DR

Subscribe now and enjoy the audio playback feature.

BotTalk

And two! I spoke to you on June 2 about an exhibition in Dijon. It concerned “Germanic paintings from French collections, 1370-1550”. This sumptuous hanging is part of a series of three. There is another in Colmar and a third in Besançon. A somewhat abstract conjunction in that one wonders who will see this trio in its entirety. But a logical path insofar as this project, launched in 2019, starts from three solidly constituted local cores. This seems obvious in Colmar, a former city of the Empire. However, this time it is a view of the mind. It was only from the 1970s that the Unterlinden Museum, which depends on the very old Schongauer Society, began to acquire old German painting on a large scale. It came to frame, if I dare say so, the rare works revolving around the “Isenheim altarpiece” by Matthias Grünewald. The absolute masterpiece that Germans come to see by coach, the ideal vehicle for pilgrimages. The purchase in 1983 of “La melancholy” by Lucas Cranach marked a decisive turning point. In 2022, Unterlinden still had a “Saint Onuphre” made of wood from the stalls of Issenheim Abbey.

An almost complete altarpiece. Probably missing the top. It was undoubtedly produced in Basel.

DR.

“Melancholy” is no longer in Colmar at the moment. She went to transplant things to Besançon, which focuses on the 16th century in this exhibition series. Unterlinden, for its part, offers a geographical display. In a huge room of the new building designed by Basel architects Herzog and DeMeuron, the exhibition follows the Basel-Strasbourg axis. Suffice to say that we are in the vernacular. It is a question of proving the coherence of what seems today to be divided by a border (which it is true that countless border crossers cross every day…). In the 15th century we were located here in the heart of the Holy Roman Empire, which extended all the way to Northern Italy. It was less a unified kingdom than a fine network of bishoprics, principalities or free cities placed under the leadership of an elected leader. In 1499, however, the victories of the Swabian War effectively freed the Swiss Cantons from this conglomerate. In 1501, Basel and Schaffhausen joined the Confederation. And from the 1520s there will be a Reformation complicating everything. I remind you that from 1530 to 1681, Strasbourg remained exclusively Protestant after a relatively “soft” iconoclasm, as in Basel. We are neither in Geneva nor in Neuchâtel…

The Dürer attributed to Albert Dürer. He came from La Fère. A Basel production from 1492-1493?

DR.

For a century, there was a cultural movement crossing the region with Martin Schongauer as its headliner. A “beautiful Martin” of which visitors today discover part of the work (not everything has been moved, there still remains an altarpiece by him and his collaborators in twenty-four parts on the ground floor). pavement!) in the exhibition and permanent rooms. Died in 1491, the man was famous in his time. Less for his painted panels than because of his copper engravings, distributed throughout Europe. We know that the young Albert Dürer came to see him on foot from Nuremberg. Alas, the master had died when he arrived in Colmar. But his family welcomed him, before he left for Basel, a city of printing and therefore illustration. The thing counts today at the Unterlinden Museum. The “scoop” of the current manifestation in fact reveals itself to be a “Crucifixion” once given to a follower of Schongauer. Current experts think of a Basel Dürer made between 1492 and 1493. The panel, which is in the obscure Jeanne d’Aboville Museum in La Fère (in the Aisne), thus receives a prestigious attribution. That said, it adds nothing to the glory of the Germanic painter par excellence.

The Martin Schongauer making the poster. This is of course the angel of the Annunciation.

DR.

Well organized by Isabelle Dubois-Brinkmann, Pantixpka de Pape (the former director of Unterlinden, who has retired), Magali Haas and Camille Broucke (the new director since 2023), the exhibition, however, mainly aims to reconstruct ensembles. There are the drawings and paintings of an unknown person conventionally referred to as the “Master of Draperies”. The grouping of what remains of the “Lösch Altarpiece”, today shared between Mulhouse and Dijon. Or in the basement (it is indeed very minor), all the known creations of an ecclesiastic Strasbourg painter from the first years of the 16th century… The thing holds up. We are in both art and art history, which is not always the same thing. The exhibition serves not only to show, but to take stock of knowledge. To demonstrate, in a way.

The decor on a purple background. Unusual!

Unterlinden Museum, Colmar 2024.

Everything is presented on the second floor on bold purple backgrounds. A color unknown in the 15th century, the red dyers not then collaborating with those of blue. It’s unusual. We are thinking a bit of a co-production with the Milka cow. But after all, why not? The didactic part is intended to be important. It actually turns out to be twofold. The aim is to explain what an altarpiece is for, how it is commissioned and who creates it. There is a very detailed contract somewhere dating back to 1462. But, even if it is in principle aimed at children this time, I also felt a reframing. In matters of religion, and even more dogmas, everything is lost today. These days we have to explain why there are thirteen people at the table when a painting is called “The Last Supper”! Nothing is therefore considered here as known and certain anymore. So we say everything. At least in broad terms. On the other hand, certain cartels could have seen themselves developed. Titles of works like “The Surrender of the Magus Hermagenes to Saint James the Greater” or “The Miracle of the Roast Chickens” do not speak to everyone. So I’ll see you again. As for the chickens, it is an edifying story of a hanged man linked to the golden legend of the same Saint James. Here she found her illustration in Strasbourg in the 1490s.

The legend of the chickens. They are reborn on the 5th and fly away to prove the words of the family coming to assure that a hanged man unjustly convicted of theft, in fact remained alive, supported by Saint James the Greater. A clear sign of his innocence…

Practical

“Color, glory and beauty”, Unterlinden Museum, Place Unterlinden, Colmar, until September 23. Such. 00333 89 20 15 50, website http://musee-unterlinden.com Open every day, except Tuesday, from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. No need to book.

The visit continues in the rooms of the museum, around the magnificent cloister. Here, a Strasbourg panel attributed to Hermann Schodeberg. around 1415. The man was undoubtedly from Basel.

DR.

“Etienne Dumont’s week”

Every Friday, find the cultural news sketched by the famous journalist.

Other newsletters

To log in

Born in 1948, Etienne Dumont studied in Geneva which were of little use to him. Latin, Greek, law. A failed lawyer, he turned to journalism. Most often in the cultural sections, he worked from March 1974 to May 2013 at the “Tribune de Genève”, starting by talking about cinema. Then came fine arts and books. Other than that, as you can see, nothing to report.More informations

Did you find an error? Please report it to us.