In recent years, indigenous children’s literature has experienced rapid growth in Quebec, offering young readers a gateway to the cultural riches and realities of the first peoples. More and more authors from these communities are taking up the pen to tell stories anchored in their traditions, while addressing contemporary themes such as identity, living together and the preservation of languages.

A text from Ismaël Houdassine

This is the case of Valérie Richer O’Bomsawin, Joannie Gill and Océane Kitura Bohémier-Tootoo, three indigenous authors who recently published their first album aimed at young readers. The trio met in Quebec in November to participate in a round table on today’s children’s literature organized by the Salon du livre des Premières Nations.

In his book Nichemis, little brotherValérie Richer O’Bomsawin speaks of filiation and transmission through the tender words of a child. As a mother of two children myself, I find it important that young people can learn about their own culture.

says the Abenaki author of Odanak.

In “Nichemis, little brother”, Valérie Richer O’Bomsawin talks about filiation. Photo: -/Ismaël Houdassine

She explains her desire to feature a narrator who tells her brother how he came into the world in her own words and her vision of things. His book also draws on his personal experience. I saw my oldest becoming very protective of her younger brother, she said. She is happy to show him the feather dance, a rite of passage that is celebrated in Odanak. In our home, the role of a big sister should not be neglected.

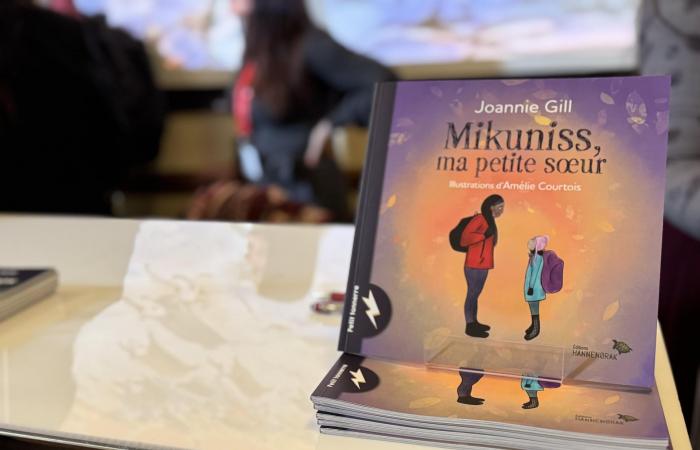

The tender work of Valérie Richer O’Bomsawin echoes that of Joannie Gill, Mikuniss, my little sisterwhose title is inspired by the story behind his daughter’s first name. I describe the beautiful complicity that unites the two sisters. The big one waits for the little one after school and, one day, she finds the right moment to explain to her why her name is Mikuniss

emphasizes the author ilnue member of the Pekuakamiulnatsh First Nation.

It is the big sister who tells, with immense kindness and in her own way, the story of the birth of her little sister. We hear new sounds, with the pronunciation of first names that Quebecers are not used to hearing.

The First Nations Book Fair offers a host of activities, including round tables on various themes. Photo: -/Ismaël Houdassine

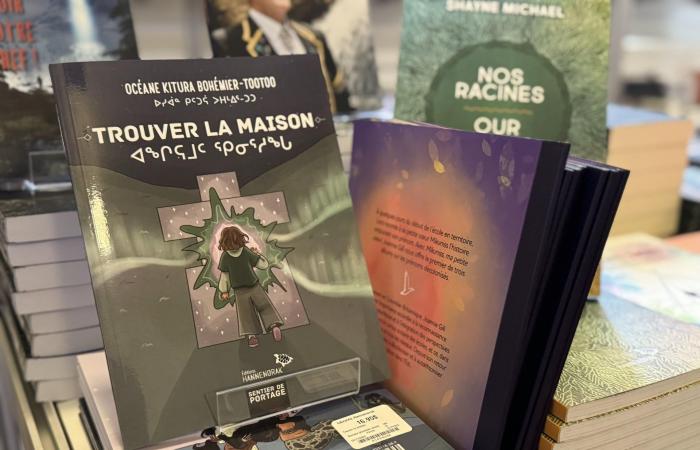

For its part, the work Find the houseby Océane Kitura Bohémier‑Tootoo, is aimed at older readers, aged 9 to 12. In his book full of intrigue and surprises, it is about exploration and a journey into the unknown for a young character in search of adventure.

The story came quietly into my head. When I started writing it and drawing the story, it took me back to my childhood in the Far North

indicates the author from Iqaluit, Nunavut.

The one who is also an artist, designer and actress shared her fascination with the immensity of the Arctic territories which we find reconstituted in her richly illustrated album. I’ve always been impressed by the idea of being an adventurer in the tundra. I think that many young people, especially those who come from the Far North, can easily understand this feeling.

There is something magical and mysterious in the immensity of the Nordic territory that I wanted to explore in my book.

Inuk Océane Kitura Bohémier‑Tootoo is the author and illustrator behind the children’s book “Find the house”. Photo: -/Ismaël Houdassine

The theme of transmission is crucial in all three books. At Océane Kitura Bohémier-Tootoo, it translates into an exchange of traditional knowledge with mythical characters from the Far North. I changed some details of the creatures so that children could read it without being too afraid

she said, laughing.

The legends she was told when she was young reflect the harshness of life in the Arctic regions. I wanted to share them, because these stories where magic and fabulous monsters mix continue to deeply inhabit me.

From shame to pride

Valérie Richer O’Bomsawin recalls that, in the not-so-distant past, it was not always good for an Indigenous person to identify as a member of a First Nation. His work Nichemis, little brother is intended to be a sort of revenge on history and a reappropriation of an identity.

I remember as a child saying that my father was indigenous, but I wasn’t. In my parents’ time, it was not glorious to call yourself indigenous. My father experienced exclusion because he was Abenaki

relate-t-elle.

For many of us, the trauma remains. With my book, I want my children, and also all the indigenous children of Quebec, to live who they are with pride, so that there is never again shame.

Born in Mashteuiatsh, Joannie Gill grew up in her community. She realized late in life the richness of her heritage. She says that the turning point came when she went to live as an adult for three years in British Columbia with her two children.

It was when I found myself outside of my community that I realized what my culture was. I then wanted to return home, so that my children had the chance to grow up at home.

For her part, Océane Kitura Bohémier‑Tootoo admits that she did not know much about Quebec society until the age of 8. I’m from Nunavut, she said. I remember at the French-speaking school asking who Marie-Mai was, and everyone was outraged that I didn’t know the famous singer.

During her childhood, she was raised in Inuit culture. His imagination was also built very early on by the tales told during family gatherings.

It was when I moved to Quebec that I had a culture shock. I felt embarrassed about being different from others. I closed myself off from my original culture, and it was during adolescence that I began to question myself and ask myself questions about who I am.

Today’s round table on children’s literature turned out to be rich in secrets from indigenous authors. Photo: -/Ismaël Houdassine

Stories with illustrations

The author Joannie Gill called on the talents of Amélie Courtois, an Innu multidisciplinary artist from Mashteuiatsh, to bring images to her book. Over the course of the project, real teamwork was put in place, she explains. She was inspired by real places in the community, such as the elementary school and the surrounding landscapes with Pekuakami, the name of Lake Saint-Jean in Innu, in the background.

The form of inspiration is the same for the book by Valérie Richer O’Bomsawin, whose drawings are signed by Valérie Laforce, who is originally from Wôlinak. The images are all made from Ndakina, the ancestral territory of the Abenakis: We came up with the idea together of adding circles to each image because the circle is a crucial symbol for the First Nations.

The characters in the album are not identified by their skin color or other physical characteristics. I wanted young readers to be able to identify with a story that is well anchored in our indigenous traditions.

Joannie Gill’s album pays particular attention to indigenous first names. Photo: -/Ismaël Houdassine

Illustrator in her spare time, Océane Kitura Bohémier‑Tootoo has imagined her own drawings which accompany her colorful work. The images came before the text. The story was built in my mind like a film

she mentions.

The three authors have in common that they have published a first book for young people. Even though each sees their future in the publishing world in a different way, they all hope to continue telling stories that feature First Nations characters.

I am preparing a second album which will be published, I hope, in 2025. Even if it is not an extension of my first book, the next opus is also intended to be a story of another traditional first name from other Firsts Nations

concludes Joannie Gill.