Artificial intelligence, an area of technology that often attracts criticism. Although it can provide opportunities for enhancement and exploration of creativity, it is also seen as a threat to artists’ rights and livelihoods. Additionally, the proliferation of AI-generated content flooding our newsfeeds is a testament to tech giants’ big investments in this sector.

In 2024, just like in previous years since the advent of generative AI, its impact on life, work, and Art has continued to fuel debate. In this article, we’ll examine how the conversation about AI has developed this year in museums, on social media, in the courts, and in the news.

AI in failure

Promotional poster of Civil War (2024), shared on the A24 Instagram account. Photo: @a24 on Instagram.

This year, although AI has been used in impressive projects like a “digital twin” of St. Peter’s Basilica, it has also raised alarms. The producers of the horror film Late Night With the Devil experienced this by integrating some images generated by AI into their work, just like the production house A24 which let an algorithm design the posters for its launch Civil War.

Strikingly, one X user used the AI to “complete” Unfinished Painting (1989) by Keith Haring, a work left unfinished by the artist to symbolize the losses caused by the HIV epidemic. The move was deemed “disrespectful” and “disgusting,” with artist Molly Crabapple telling Hyperallergic that such use of AI represents “a way for mindless minds to siphon off all the soul, pathos and “humanity of art.”

Keith Haring, Unfinished Painting (1989). Photo : © Keith Haring Foundation

With surprising audacity, the London Standard not only used AI to create art, but to resurrect a critic from oblivion. In October, the newspaper published an AI-generated review imitating the style of its late critic Brian Sewell, accompanied by an equally generated portrait of Keir Starmer. As critic Ben Davis pointed out, this exercise was more of a “cheap provocation” than a real reflection on the impact of AI on arts journalism.

Illustration of Infinitive Wonderland in the style of John Tenniel.

At the same time, Davis observed that AI-generated art was degrading, including the integration of AI photography features on Samsung’s new Galaxy phones and the Project Infinite Wonderland from Google Labs, which offered less than sensible interpretations of John Tenniel’s art. These results demonstrate the frenzy of large companies to invest in this booming sector, as illustrated by Mark Zuckerberg’s name change to direct his company towards the metaverse. Its Facebook platform has become a playground for a new form of “natural waste”.

AI in victory

Refik Anadol. Installation view Living Archive: Nature (2024). Photo : courtesy Refik Anadol Studio

However, that doesn’t mean artists haven’t found creative ways to use AI Refik Anadol, a digital artist and strong AI advocate, introduced his first Large Nature Model in January. Built on data from sources like the Smithsonian Institute and National Geographic, as well as LiDAR and photogrammetry techniques, this open-source model generates fantastic images of nature, which Anadol showcased in the installation Living Archive: Nature (2024) in Davos and in the exhibition “Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive” in London.

For their part, the French collective Obvious presented its “mind-to-image” project, allowing an AI to generate images based on the user’s imagination. One of the first results, an image titled Stagnant Elixir’s Sweet (2024), was sold for $28,000 at Christie’s.

Rendering the Have vs AI by Ai Weiwei on the Piccadilly Lights in London. Photo: © CIRCA.

In January, Chinese artist Ai Weiwei also made his debut in this field with Have vs AIa work that covered London’s Piccadilly Circus with AI-generated answers to its philosophical questions. Later, Cai Guo-Qiang, furthering his research into extraterrestrial intelligence, orchestrated a fireworks show, inaugurating PST Art in Los Angeles, in collaboration with his AI model cAI™. Before the show, he said the technology was “a revolutionary tool and a tool for revolution.” (Unfortunately, some neighbors weren’t thrilled.)

Finally, as you read this, performance artist Alicia Framis is officially married to her AI hologram boyfriend, Ailex. Congratulations to the newlyweds.

AI on the market

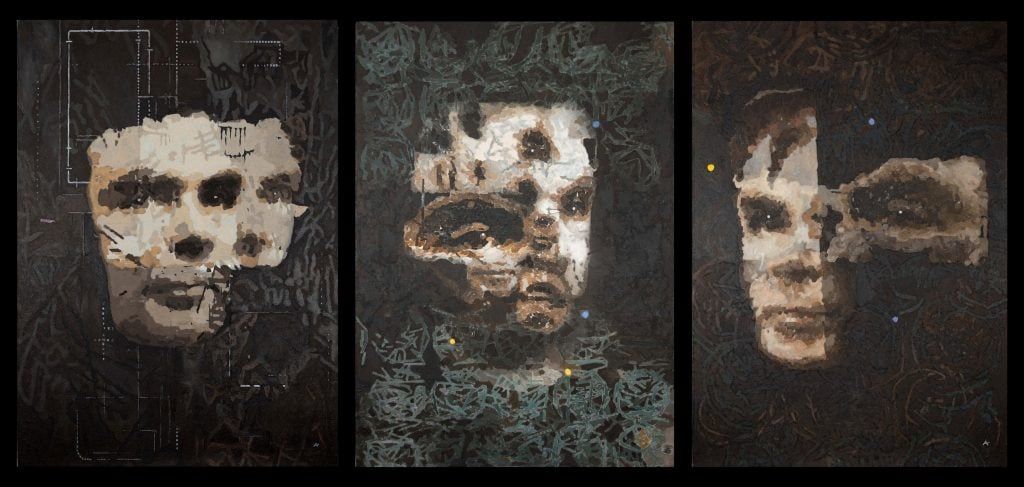

Ai-Yes, A.I. God (2024). Photo : courtesy Sotheby’s.

Obvious has partnered with digital artist Botto, aka Mario Klingemann, on the auction market this year. However, all of this was overshadowed by the non-human artist, Ai-Da, whose work A.I. God (2024) was sold for $1.1 million at Sotheby’s. This triptych, a tribute to computing pioneer Alan Turing, is the first work by an AI robot to be sold at auction. Gallerist Aidan Meller, behind Ai-Da, said the robot’s images “question where the power of AI is heading.” Toward the bank, perhaps?

AI in authentication

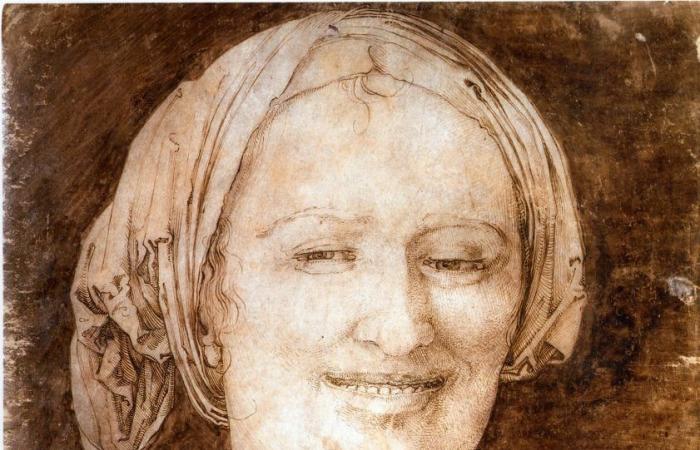

Albrecht Dürer, Vna Vilana Windisch (1505). Courtesy of Diego Lopez de Aragon.

This year, the Swiss company Art Recognition made headlines for the authentication of a Dürer drawing, uncovering around 40 counterfeits sold on eBay. These determinations demonstrate the promise of AI in the field of authentication, although, as the case of de Brécy Tondothere is still a long way to go before establishing complete trust. The company manager said: “It is more important than ever to emphasize the need to meet rigorous scientific standards”; adding that “otherwise the entire field of AI could face criticism, and we would all suffer the consequences.”

AI facing artists

Images generated by the Stable Diffusion text image generation tool. Photo: Stable Diffusion.

“It would be impossible to train today’s leading AI models without using copyrighted materials,” OpenAI said in a statement to the British House of Lords in January. This admission is remarkable, but hardly surprising to the many artists whose works were used to train these models. In August, a California court validated these fears by allowing a lawsuit filed by visual artists against Stability AI, Midjourney, DeviantArt, and Runway AI Worryingly, the judge said the Stable Diffusion model was “created to facilitate this offense by design.”

Outside of the courts, artists have found several ways to denounce the infringement by AI Nightshade, a tool protecting artists’ works by “poisoning” generative models, was successfully launched: the software was downloaded more than 250,000 times in a week. A group of activists even hacked Disney’s Slack in protest of the company’s approach to AI. In October, around 11,000 artists, musicians, writers and actors signed an open letter condemning the drive of AI on creative works as “a major and unjust threat.”

OpenAI has announced the launch of its AI video generation tool Sora to the public this year. Photo: CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images.

Recently, OpenAI’s Sora AI video generator had its source code leaked by artists who had early access to this tool. Around 20 creatives harshly criticized the company in an open letter accompanying the leak, denouncing that they had been “lured into artistic washing”. Their participation, they clarified, was “less about creative expression and criticism, and more about public relations and publicity concerns.”

However, the cleverest move came from photographer Miles Astray, who managed to enter a non-AI photo into an AI-generated design competition — and won a prize. The bronze prize was canceled once the deception was revealed, but its message was understood. “Winning both the jury and the public with this image,” he said, “was not only a victory for me, but for many creatives.”

It seems crucial to continue to monitor how AI interacts with the artistic world, because its implications go far beyond simple technological tools. How to balance innovation and respect for artistic rights? This question deserves to be explored further in future debates.

- -