For safety, the Gruyère Space Program’s “Colibri” rocket is connected by a cable to the boom of a crane. But it already lands on its own at the place of its takeoff.

Gruyere Space Program

In the field of aerospace, the trend is towards recyclable rockets. Certain student projects in Switzerland contribute to this development. Reporting.

This content was published on

September 27, 2024 – 09:30

Audrey Vorburger conducts research on space instruments and our solar system. The astrophysicist and planetologist from the University of Bern therefore depends on rockets for her work.

“Switzerland is already known for its high-precision engineering and its ability to develop complex scientific instruments,” explains the researcher. A space program would make it possible to highlight and develop these assets.

“Access to space is no longer reserved for major space nations. With technological advancements and internationally accessible launch capabilities, smaller countries can also play an important role.”

Student projects could contribute to the development and promotion of Swiss space technology as well as the training of future specialists in this field. We visited two of them.

The rocket that lands upright

We are in a gravel pit in the Gruyère hinterland, in the canton of Fribourg. It’s a little after four in the afternoon. A young team is working on the final preparations. Every gesture is perfect. Installed in a container and placed on a workbench, the object which attracts all the attention here undergoes a small repair on one of its four legs.

Its dimensions: 2m45 high, 100 kg. Its name: Hummingbird. What makes this rocket unique in Europe: it can land safely on earth while standing vertically on its feet. But it took a long time to get there.

Behind the “Gruyère Space Program” projectExternal link» (GSP) are five young students who have known each other since secondary school and who have followed the same path together, from the gymnasium to the Federal Polytechnic School of Lausanne (EPFL).

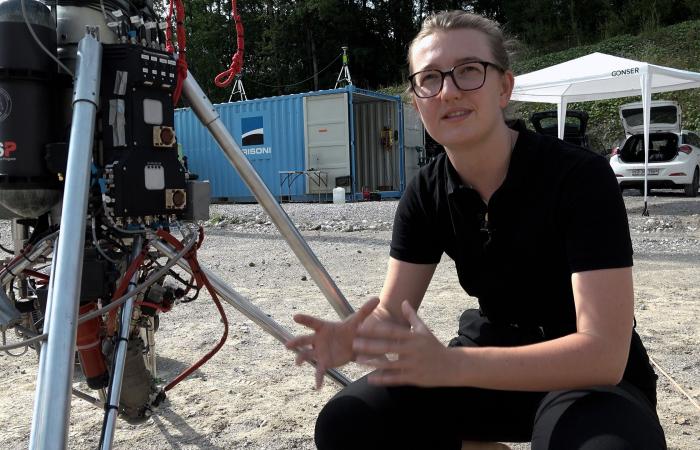

“No one in Europe has ever launched and landed a rocket with a payload on its feet,” explains Julie Böhning, 25, a robotics student and spokesperson for the team. “It’s great to have developed this project together.”

Julie Böhning, responsible for steering, navigation and control systems, has been part of the team since the beginning.

swissinfo.ch / Michele Andina

Julie Böhning and her four fellow students have been tinkering with rocket projects for six years now. Inspired by the SpaceX project in the United States, whose rocket can land on Earth according to the same principle, they developed and built Colibri from A to Z. Since its beginnings, the group has grown and has now 15 people.

In the container, the team mounted all the rocket elements on a test stand, so they could be tested independently of each other. Tanks, engine, electronics, sensors.

The countdown is on

Eight people are present in the gravel pit today, including founding members Jérémy Marciacq (26 years old) and Simon Both (25 years old). On their laptops, they check various data feeds. After the test, they will analyze the results in detail.

At a safe distance, the team quickly set up a mobile control center. The rocket is refueled, a small drone is still carrying out a check circle around the Colibri, ready to take off. With full tanks, it is too dangerous to go near them.

“Five, four, three, two, one”, the countdown is on. Then the noise is heard, the rocket rises as expected a few meters in the air. Today, for its 25th attempt, it must deviate slightly from its trajectory in the air, in order to prove that it can once again navigate autonomously towards the small take-off and landing platform.

Apart from a few details, the test is conclusive. “Today’s objective has been achieved,” says Simon Both. It was important to test the new algorithms for landing the rocket, algorithms that the team, of course, programmed themselves.

In Switzerland, such a test requires special authorization. But because the rocket is connected to a crane, suspended at its end by a cable with emergency stop function, it is legally considered a ground object. In addition, the operation must take place at a distance of at least 200 meters from the nearest home, which is more than respected here.

Testing the “Colibri” rocket in a gravel pit near the small town of Gruyères.

Gruyere Space Program

Claude Nicollier as mentor

They built the rocket with simple and cheap materials. “Typically, the Colibri’s tanks are tubes from a construction site, which we received and modified,” explains Julie Böhning. The team also relies on 3D printing in order to be able to change certain parts as quickly as possible, independently of the suppliers.

The students take care of everything themselves, but also rely on sponsors. The small group now has 55 industrial partners. Among them, the company which provides them with part of the gravel pit and the crane free of charge. To be able to use this machine, Jérémy Marciacq had to follow specific training.

With Claude Nicollier, the first Swiss astronaut, young rocket fans have found a renowned mentor. In addition, as Julie Böhning points out, their student status allows them to contact all kinds of specialists around the world, who are happy to help them for a few hours by providing them with advice.

But what is the objective of their project? “We want to show that in Europe too, we are capable of launching rockets and bringing them back down,” she explains.

Parachute system

Another day, another place. We are in a hangar at the Dübendorf military airfield in the canton of Zurich, where Swiss aviation made its beginnings. Today, some of the hangars house an innovation park which hosts different start-ups and student projects.

These include the student-led space project ARIS, which is supported by the ETH Zurich and other universities and institutes. A few more or less large rockets, from previous tests, are lined up in their premises.

The current “NICOLLIER” rocket project even bears the name of the Swiss astronaut. He participated online in the rocket’s second technical review and provided his feedback to the team, explains Felix Hattwig, the 21-year-old project manager who studies physics at ETH Zurich.

Here too, we are banking on a reusable rocket. It is equipped with two parachutes, a so-called guided recovery system. A small parachute brakes the rocket as soon as it reaches its highest point in flight, explains mechanical engineering student Matteo Vass (20), head of the recovery team and therefore responsible for the braking system.

The guide parachute, larger and controlled by an autonomous software system, then comes into action about 800 meters above the ground to bring the rocket to the landing point.

Felix Hattwig (left) and Matteo Vass attach the electronics for the autonomous parachute control.

swissinfo.ch / Christian Raaflaub

Currently, the team is carrying out so-called “drop” tests. She is helped in this by the Swiss army, which drops the rocket from a helicopter in order to simulate the landing. Of course, these tests take place far from inhabited areas, above military areas, for example in the canton of Glarus or in the Bernese Oberland.

The rainy spring, however, played a bad trick on the team: only two of the thirteen planned fall attempts could be achieved. But the video they show us illustrates a test that is already working well, with the rocket finding its landing spot as planned.

The growing importance of autonomous piloting

“We have reached the new era of space, where it is not just about the rocket itself, but about the new systems that revolve around it,” explains Felix Hattwig. It is indeed about autonomous control, but not only: “Our rocket goes beyond guided recovery. Even if it’s a big challenge,” he continues.

“We are also trying to achieve technical innovations in other parts.” He particularly mentions interchangeable computer boards or air brakes, components for which the team is exploring new avenues.

As with the previously mentioned project, the 43 active members work alongside their studies and receive neither salary nor credits. So they put a lot of heart into their work. The two students, fascinated by space since their childhood, are happy to be able to realize their dream, and also rely on sponsors, numbering 40 to 50.

Their rocket has never taken off yet, but previous ARIS projects have already laid the foundations for such a step. Currently, the first launch is planned for the end of October in Switzerland, explains Felix Hattwig. The end goal will be to launch three different payloads, i.e. satellites.

The “NICOLLIER” project rocket with its main parachute during a so-called “drop” test.

ARIS

The Gruyère Space Program has planned its first demonstration flight for the end of September, with Claude Nicollier among the guests. The students will take advantage of this event to reveal the follow-up they plan to give to the project once it is completed.

“We all get along so well that we want to move on to new horizons in the form of a business,” explains Julie Böhning. It will no longer be rockets, but the same technology. The rocket builder will say no more.

+ Our report from two researchers

who also depend on rockets to transport their instruments into space.

Plus

Plus

Two Swiss scientists search for ice on comets

This content was published on

Jul 23, 2024

Thanks to an innovative instrument, two astrophysicists from the University of Bern hope to unravel a little more the mystery of the formation of the solar system.

read more Two Swiss scientists search for ice on comets

“A good practical basis for training”.

“What these students, and others, are accomplishing there deserves great respect,” writes the “Swiss Space Office”, the Confederation’s competence center for national and international space affairs, when asked about this.

Swiss projects are “very successful” in international comparison. They constitute “a good practical basis for the training of students, in order to prepare them for their future tasks in the space field”.

It is obvious that the “costs – recyclability – sustainability” issues will remain tomorrow and the day after tomorrow a challenge for all people active in space research and space agencies.

Text proofread and verified by Veronica DeVore/ml, translated from German by Lucie Donzé.

Plus

Plus

Want to know more? Subscribe to our newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter for the Fifth Switzerland and receive our best articles in your inbox every day.

read more Want to know more? Subscribe to our newsletter