We descended into the darkness, crunching over broken glass, down three flights of steep stairs.

I could make out some offices with my torch, and at the end of the corridor, a set of large metal gates.

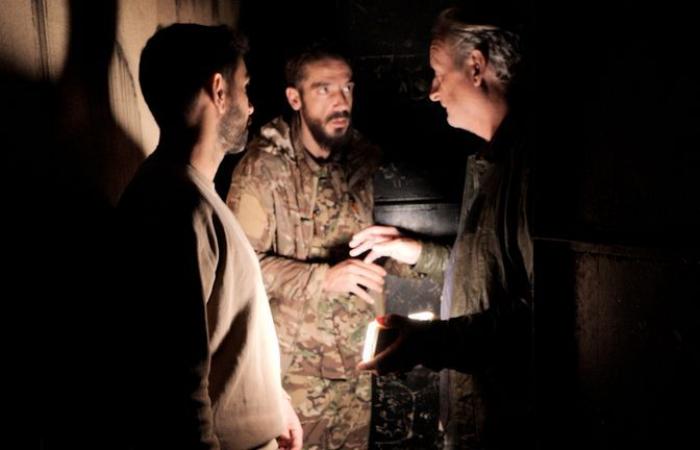

We were following a rebel soldier beneath a complex built by Syria’s internal security services in the heart of the city of Homs.

The entrance to the jail with a torn-down picture of Bashar al Assad

He took us towards the cells where an unknown number of prisoners were held, tortured, moved on to other prisons, or just murdered where they lay.

As I followed the rebel soldier, Abu Firas, he told me he deserted the Syrian Army because of the torture he had witnessed in cells like these.

Syria latest: Fears of ISIS prison breakouts

In the pitch dark, we walked through the cell block – an eerie, narrow passageway, past opened cell doors, some with padlocks still attached.

I peered inside, the cells were no more than 6ft long and 4ft wide.

They looked like large coffins, which for many, they would become.

In some cases, people were kept here for years. As we passed the cells, we saw the remains of meagre amounts of food; one piece of bread and a sort-of thin soup.

Sky News chief correspondent Stuart Ramsay talking to Abu Firas inside the prison

‘They killed them here’

Abu Firas told me prisoners were fed, but only to keep them alive.

“They didn’t give them food because they care for them, they did it to try to take information,” he said.

“So they keep them alive, so they can be interrogated?” I asked him to confirm.

“Yes, and once they finished the investigation, they moved them somewhere else or they killed them here.”

A smashed picture of the regime leaders

The regime murdered people here as soon as they got whatever they needed to know – maybe they got nothing out of the prisoners, they were still killed.

In Homs, random detention was continuous, and nobody was safe. I was called over to look at the name of a woman “Fatima” scratched on the door of a cell.

It wasn’t just men held here, women and children were held here too.

????Listen to The World With Richard Engel And Yalda Hakim on your podcast app????

“They were protesters, maybe they were passing randomly in a street and there was a protest,” Abu Firas explained.

People were lifted off the streets for any reason.

Many who were brought to this place, were charged, they were told, with terrorism – a broad charge anyone could get for disliking the government.

Read more:

Inside Assad’s abandoned home

Assad critic returns home after 14 years

A pile of weapons and ammunition found in the jail

‘They used to torture my brother in front of me’

Without my torch, I couldn’t see much. That too was part of the torture for the prisoners here.

“The regime used this method, so the people don’t know if it’s day or night,” Abu Firas explained.

He witnessed torture as a soldier. I asked him if he was tortured at any point too.

“So much, electricity and different tools, you would always have blindfold,” he told me.

“The ways they used to torture us, me and my brother, they used to torture my brother in front of me, and me in front of my brother, for psychological pressure.”

The cells are beneath an internal security complex in the heart of a housing estate with large apartment blocks. A prison this close to the community feels like yet another message of repression to the population.

It seems the officers who worked in this complex left in a hurry. There are half-drunk cups of tea, stubbed-out cigarettes, food on plates, and jackets still hanging on office chairs.

In one of the rooms, we found a stockpile of weapons and ammunition, much of it supplied by Russia – all abandoned.

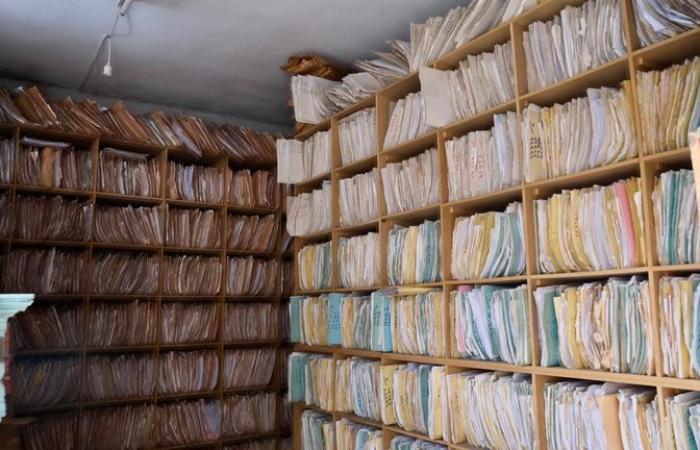

Abandoned too were files – thousands upon thousands of them detailing the lives of civilians and their assumed political beliefs.

A hastily abandoned office inside the prison

Thousands of intelligence files found in the jail

Everyone in Syria was spied upon, and we were told the people in these files were on a watchlist.

We peered into another room, this one underground. It was burnt out, documents turned to ashes, some still smoking from the heat.

These were the files on the prisoners themselves, we were told, and they were burnt as the regime collapsed.

Documents destroyed seemingly by fleeing guards and workers in the facility

Who the prisoners were, and what happened to them, may never be known.