For several years, scientists have been getting involved beyond their research work. Outside of their laboratories, they believe that they must act to respond to current challenges. The “Scientists in Rebellion” collective brings together 500 of them. An assessment of their experience has just been published: interview with two authors of the work.

After four years of activity, the collective “Scientists in rebellion” (SER), which brings together around 500 researchers, teacher-researchers, doctoral students and post-doctoral students committed against climate inaction, is releasing a collective work entitled “Leaving the labs to save the living.” He invites scientists to “get out of neutrality”.

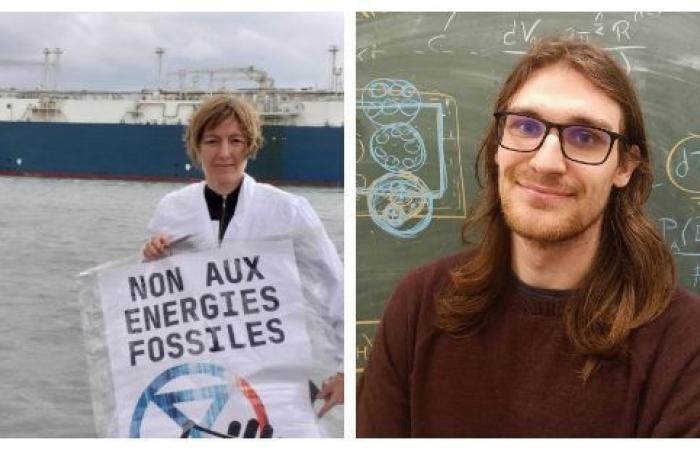

Meeting with two of the co-authors, Andrée De Backer, researcher in materials sciences at the University of Lille and Jack Berat, doctoral student in astrophysics at the École normale supérieure.

Heavy Jack : The collective is made up of local groups, in certain large cities in France. It’s a very horizontal operation. If one of the members has an idea for action, whatever it may be, they can implement it with the collective at the national or local level. Everyone brings their own skills and desires. Working groups can also be formed on a particular issue, as was the case for the writing of the book.

Andrée De Backer : “Scientists in Rebellion” is also the French branch of the global movement “Scientists Rebellion”which promotes environmental causes on a global level, taking into account aspects linked to decolonization and climate injustice.

On the scale of France, we are rather immersed in local struggles, such as, recently, the mobilization against the A69. But we are also leading convergent struggles, like in May, with the “Total Liquidation” campaign, which aimed to denounce Total Energies’ investments in fossil fuels. “Scientists in Rebellion” is also linked to other collectives.

Why did you want to publish a work?

J.B. : The collective has reached a certain maturity. It seemed important to us to express our commitments and to disseminate our ideas, targeting our colleagues in particular, to show them that it is possible to get involved. In addition to scientists, we are also citizens, whose commitment can perhaps strengthen the word we speak, particularly to the media.

A.D.B. : This book is also a means of draw up initial feedback on our actions.

Actions which are mainly carried out by civil disobedience…

J.B. : This mode of action is complementary to other, more traditional means of control.

History shows the value of non-violent civil disobedience. We can write op-eds, participate in intergovernmental meetings, but I am not sure that these actions sufficiently show the urgency of the situation. Civil disobedience allows to adopt another posture, to go further.

Your work is thus a call to scientists to “move beyond neutrality”.

J.B. : Neutrality is impossible to achieve and is not desirable. The objective of this book is to show that thewe can assume this part of commitment, faced with an emergency that we do not want to simply describe.

We want to take part in the transformation of society, so that it is fairer and more sustainable to live in. This involves maintain our scientific rigor, which is not antagonistic to commitment.

The CNRS ethics committee recognizes the “freedom of scientists to engage publicly”, while the University of Lausanne says it “promotes a culture of engagement”. Do you feel supported by your institutions during your actions?

A.D.B. : We receive some support. But our institutions remain in the grip of a system of influences, and dictate to us contradictory injunctions.

J.B. : Exactly. We are told that we must commit to saving the planet, but at the same time we are asked to publish on research that is often harmful to the planet…

A.D.B. : We do not only expect support from them when we take action: we want them to get involved at their level to make structural changes.

Are fears of professional repercussions a barrier to commitment? In the book, you say you conducted “crash tests” in order to identify whether the members of the collective had been penalized for access to positions or career advancement. Tests which were “generally passed positively”…

A.D.B. : Indeed, but this crash test was not positive for at least two people in our collective, who felt isolated from their colleagues.

JB: Personally, I thought a lot before committing. Engaging in a process of rebellion has consequences, even if only personal. It’s scary! But the fear of the emergency at stake is greater…

At the end of your book, you wonder about the strategy to adopt: continue actions of civil disobedience or “return to less engaging but more massive mobilizations”.

J.B. : I understand that we want forget the notion of efficiency to multiply the number of actionsbut to what extent do we want to reduce our actions to that? This is a question that we often ask ourselves, from the prism of efficiency.

A.D.B. : We embrace the radical aspect of our collective. But in the desire to expand our ranks, it may be necessary to accept softer, more diluted forms of this posture… However, at the risk of losing our identity, becoming less legible, and ultimately losing certain members.