Refusal of disappearance, difficult management of digital heritage, modification of the relationship with finitude… the increasingly strong presence of digital technology in our daily lives modifies our link to death and mourning. A recent study from Zurich examines these issues.

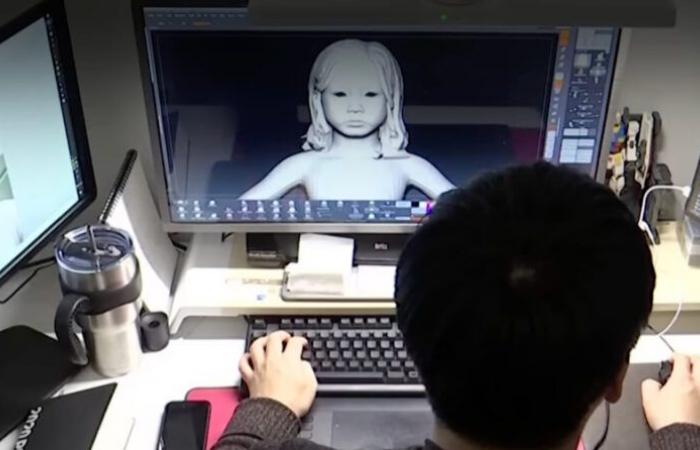

“Mom, where have you been? Have you thought of me?” These were Na-Yeon’s words to her mother in 2020. But Na-Yeon died suddenly of illness in 2016, at the age of seven. It was therefore not the little South Korean girl, but her digital avatar, created as part of a television show. Her mother, in tears, was able to converse with her and even touch her in a virtual reality.

An episode mentioned in the study Death in the digital age (2024), a study carried out under the direction of Jean-Daniel Strub, director of the ethix office. As part of the Commemoration of the Dead, celebrated on November 2 in the Catholic Church, the Protestant ethicist and theologian clarified a few points for cath.ch.

Are we heading towards a multiplication of experiences such as those of Na-Yeon? The massive creation of avatars of deceased people?

Jean-Daniel Strub: It is about there from a field known as “Grief Tech”, which refers to digital technologies and services designed to support individuals and families in the process of grieving and coping with loss. It is still a niche reality, which mainly concerns countries like the United States, China or South Korea, and very little Europe. For us, it is different from “Death Tech”, which concerns more the management of advance directives, the organization of funerals or even memory spaces.

Could “Grief Tech” become widespread?

It is impossible, from our data, to formulate more than hypotheses. The theme of avatars of the deceased is part of the broader theme of ‘Companion Bots’ or ‘Chat Bots’, virtual “companion” entities. If the phenomenon has taken on a certain extent, it is difficult to say that it will continue. A recent program on German-speaking television SRF put five people in contact with a ‘Companion Bot’ for three weeks. The participants quickly began to get bored, particularly because of the lack of authenticity in the interviews.

So we won’t soon have our grandmother as a virtual avatar on our computer or as a humanoid robot in our living room…

This will largely depend on this theoretical space that we call the “Uncanny Valley”. When the machine is both too much and not enough human-like, it causes a feeling of unease, discomfort. It is not certain that a robot that is most human-like will be best accepted. The industry is constantly working on the best way out of this “valley.” But I don’t imagine that, apart from significant technical progress regarding the emotional response and physical appearance of these virtual entities, these applications can move beyond the niche.

The report Death in the digital age was commissioned by TA-SWISS, Foundation for the Evaluation of Technological Choices and competence center of the Swiss Academies of Sciences. The objective of TA-SWISS is to reflect on the repercussions – opportunities and risks – of the use of new technologies. The study was carried out by the ethix office – innovation ethics laboratory (Zurich), in collaboration with the University of Lausanne, the Vaud University Hospital Center (CHUV) and the Haute École d’Ingénierie et de Gestion of the Canton of Vaud (HEIG-VD).

A more important theme is that of “personality” which almost everyone now has on the internet.

Following a death, the inheritance of intangible heritage – personal data – often leaves loved ones and friends distraught and powerless. Without the accesses and passwords of the different accounts, it is almost impossible to update the data of a deceased person or delete their profiles in a timely manner. In addition, data or accounts, which are not protected by copyright and therefore have no material value, are not part of the estate.

Does this reality also carry psychological risks?

One of the risks is an unsolicited meeting with a deceased person, for example an automatic notification on a social network coming from their profile. Such an experience can certainly cause emotional shock in grieving people.

What are the other dangers of technological advances linked to death identified by your study?

We deal in particular with the phenomenon of ‘Second Loss’. Many applications in the field of “Death Tech” and “Grief Tech” appear, but also quickly disappear. If you have built the profile of a deceased loved one, consult it regularly in a dedicated application and it stops its services, this ‘second loss’ can certainly increase the difficulty of grieving.

“Using digital tools can certainly present a risk of not being able to overcome grief”

Beyond the emotional aspect, what ethical and social problems can arise?

Grief, and the relationship with death in general, represent very ambiguous aspects. They will be experienced very differently depending on the person. It is therefore impossible to generalize. Using digital tools can certainly present a risk of not being able to overcome grief, due to not having done enough work to accept the disappearance of your loved one. But for others, technological resources can also make grieving easier.

We asked ourselves the question of the “societal modification of the ephemeral”. To what extent does technology provide us with innovative solutions to overcome human finitude? For the moment, it most certainly cannot, because not all the components that make up a human being can be reconstituted virtually.

Is there therefore a risk of losing the sense of finitude?

The value of finitude has been a contested notion since Antiquity. If we defend the philosophical perception that finitude gives meaning to life, it is clear that if this limit fades, this can have an impact. But, again, it is too early to draw conclusions.

When faced with the loss of a loved one, isn’t the confusion between the real and the virtual the greatest danger?

This confusion is not specific to this area, it can exist in many other digital sectors, such as video games, for example. But it is clear that bereavement makes people particularly vulnerable, which puts them at greater risk, not only of losing contact with reality, but also of allowing themselves to be manipulated or abused.

Can applications of what we call “Digital Afterlife” compete with religious rituals?

I find it hard to imagine. We have not identified any application that would replace farewell rituals. These offers mainly target preparations for death or commemoration, but not transition rites.

“The services offered must take measures against the ‘second loss’, disinformation, manipulation or even confusion between the real and the virtual”

In fact, these apps can even make funeral preparations easier, or provide new ways to honor memory. Technology makes it possible to decentralize memories. People who have difficulty going to the cemetery can honor a deceased person from a distance. This type of offer undoubtedly allows certain people to better grieve. Technological development also has its share of positive aspects.

Ultimately, what are your thoughts on these technologies following your study?

The main interest was to demonstrate what it is already possible to do and what could still be done in the field of “Digital Afterlife”. The implications can be multiple, both positive and negative.

In any case, we must keep in mind that these technologies target people who are in extremely individual, intimate and delicate processes, who are experiencing a period of great vulnerability. We therefore believe that the services offered must take this into account and take measures against the ‘second loss’, disinformation, manipulation or even confusion between the real and the virtual. Applications must avoid unwanted confrontations with a deceased person and facilitate the possibility of erasing data.

At the public level, it is about becoming aware of the need to plan their digital succession. In this sense, we recommend organizing campaigns and information sessions. (cath.ch/rz)

© Catholic Media Center Cath-Info, 01.11.2024

The rights to all the contents of this site are registered with Cath-Info. Any distribution of text, sound or image on any medium whatsoever is subject to payment. Saving to other databases is prohibited.