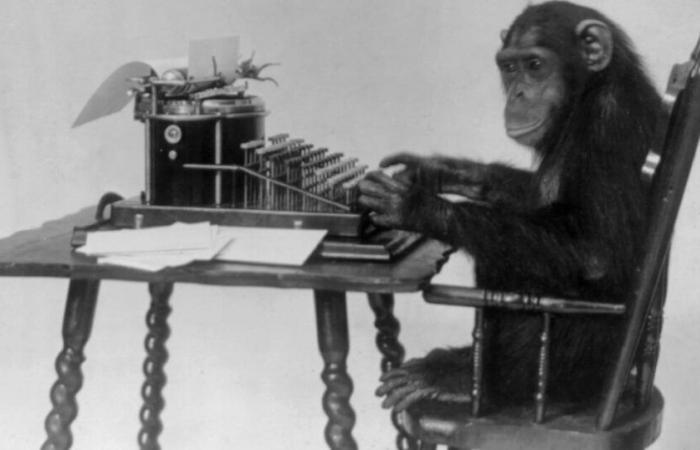

In mathematics, a well-known thought experiment posits that given enough time, a monkey typing on a keyboard could produce all of Shakespeare. This is not the opinion of two Australian mathematicians who undermine the “scientific monkey paradox”.

Given enough time, something improbable but technically possible can become probable. This is what this hypothetical proposition which was used at the beginning of the 20th century by Emile Borel and Arthur Eddington says: the two scientists wanted to illustrate the time scales implicit in the foundations of statistical mechanics.

But then, could a monkey really produce, by chance, poetry and plays that could go down in history? Two Australian mathematicians have calculated that if all the world’s chimpanzees had the duration of the Universe, they would “almost certainly” never be able to reproduce the works of the British playwright.

External content

This external content cannot be displayed because it may collect personal data. To view this content you must authorize the category Social networks.

Accept More info

Mathematicians Stephen Woodcock and Jay Falletta from the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) looked at the problem from another angle in their study published in the journal Franklin Open this week: “The infinite monkey theorem only considers the infinite limit, with an infinite number of monkeys or an infinite period of time for their work”, note Associate Professor Woodcock on the UTS website.

“We decided to examine the probability that a given string of letters would be typed by a finite number of monkeys in a finite amount of time corresponding to estimates of the lifespan of our Universe,” he says.

One keystroke every second for 30 years

The two scientists thus calculated what a monkey could produce typing the keys of a thirty-character keyboard – including all the letters of the English language as well as the most common punctuation – at the rate of one keystroke per second for 30 years. .

They also used a theoretical duration of the Universe of one gogol years, i.e. 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 0 000 000 000 000… that is to say the number 1 followed by one hundred zeros.

The two friends dismissed trivial aspects of the experiment, such as the diet of the monkeys or their means of surviving the extinction of the Sun, expected in a few billion years.

According to their calculations, a single monkey would have a 5% chance of randomly typing the word “banana” by devoting its entire existence to it. A word otherwise absent from the 884,647 written by William Shakespeare throughout his work.

Monkey work

The mathematicians wanted to give monkeys a chance by “recruiting” chimpanzees, the primate closest to humans. The current population of chimpanzees in the world is estimated at around 200,000 and the study assumed that it would remain stable until the end of time.

Alas, poor ape, how thou sweat’st! Alas, poor monkey, how you sweat!

The conclusion is that even such a workforce would be quite insufficient. Its chances of success would be “not even one in a million,” study co-author Stephen Woodcock told New Scientist.

“If each atom in the Universe were itself a universe”, to repeat the experience so many times, “this would not happen either”, he adds, without hesitation. “Increasing the number of chimpanzees or their keyboard typing speed would not change anything,” according to the study.

Ironically, she concluded that William Shakespeare himself was able to answer the question of whether “the work of a monkey could really replace human effort as a source of knowledge and creativity”, with this quote: “Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 3, Line 87: ‘No’.”

Stéphanie Jaquet and ats