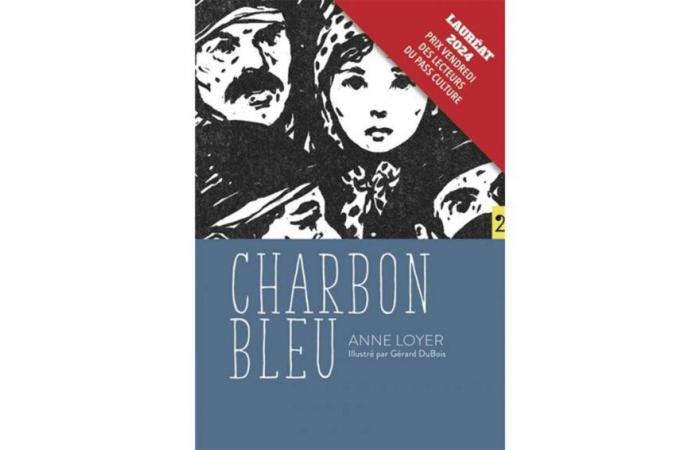

Titre : Blue charcoal

Author: Anne Loyer

Illustrator: Gerard DuBois

Editions: Two

Publication date: November 2023

Genre of the book: Roman

Recently awarded the Culture Pass readers’ Friday prize, the book Blue charcoal by Anne Loyer finds, in this circumstance, the opportunity to be presented to our readership, in order to honor this beautiful work of children's literature, capable of raising awareness of themes, certainly difficult, but in perfect adequacy with the ambition of Éditions D'eux, which intends to read “an element of transformation for the child. »

In the Bonnemère pit, the beating heart of the economy of the village of Marlin in northern France, where the Fourche company subjugates the bodies of men, women, boys and girls, as well as their minds, in order to profit of their work force, Ermine rushes in, she who, thanks to the sesame of the school certificate that she was about to obtain, nevertheless seemed promised a future other than that reserved by the mine. It's because the Reaper decided otherwise: she took over Ermine's father, depriving his family of its ferment of unity and, by threatening their already poor household with sinking into poverty, stifling the dreams of emancipation of Ermine. As if, because of her social class and her first name, which is inseparable from her appearance, she was predestined to fall.

An inexorable fall

Blue charcoal is a nineteenth-century story relating this inexorable fall, the wormy fruit of a socio-economic heredity which imprisons us and from which we rarely escape, almost miraculously. Ermine is exiled far from heaven, into the bowels of the earth. In Sheol, where the bodies of miners descend every day, matter overwhelms them: particles of charcoal infiltrate their facial orifices, inoculating themselves into their organism where they carry out their disastrous work and cover their skin, never leaving it. than with bath water – the only pleasure that the miner grants himself at the end of his arduous day.

The narrator documents with empathy the daily lives of the miners: he describes their frantic work and their conflicting relationships, fueled by the employer's demand for optimal productivity. By focusing on Ermine and those close to him, he also becomes the spelunker of their inner lives. The narrator shows us an Ermine crushed by this new condition, imposed since the tragic fate of her father, which propelled her resentful brother, Guy, to the rank of head of the family. Guy deplores having lived in the shadow of Ermine, whose privileges, whether emotional or academic, continue to revolt him: although she is now like a fallen angel, his anger remains strong and bursts out at the slightest opportunity against his little sister, who, for her part, seeks to obtain forgiveness from her brother.

In short, the fall insinuates itself everywhere and sets the backdrop for the story. Conceding nothing to meritocratic fiction, Anne Loyer's novel adopts a pessimistic outlook that is reinforced by most of the twelve illustrations by Gérard DuBois. But it would be wrong to stop there: we would then lack consideration for the other side of this book, the poetic side of ascension.

A fictional ascent

At the bottom of the abyss where she wears herself out, Ermine meets Firmin, a skinny young man whose words are so many windows opening onto vast landscapes. In Hell, all that remains for the damned is to dream of Heaven, to invoke it in order to live from it, at least virtually. Firmin achieves this through his words, which arouse for Ermine a bundle of sensations, capable of making his excarnation possible: they offer him the opportunity to embark “as in a train to a star” (Van Gogh).

This train, by which she ventures, cannot save her on the material level, but, architected by the verb of Firmin and the verses of Lamartine, it nevertheless indicates the destination of an imaginary pleroma – this star — which constitutes the promise of a life free from ugliness, foreign to one's bodily condition but always accessible in spirit. Ermine then lives torn between her body, exhausted by the harshness of her daily work, and her lively mind, which defuses the influence that condemns her to waste away.

The ascension may well be fictitious, but it nonetheless abstracts the characters from the violence that crushes them: Firmin is his, Ermine is his, and both, even if it means appearing as flat dreamers, build together this imaginary world which gives them allows you to lead a distracted life, woven with the threads of poetry.

If Anne Loyer's book seems to have a Gnostic resonance, notably through the temptation that awaits the characters that reality imprisons – that of abstracting themselves, through imagination, from a corrupt world – it never lets go of a raw realism, which does not compromise on the violence of the exploitation of man by man. Blue Charcoal is a novel with bewitching prose and immersive illustrations, whose obvious empathy towards its characters makes it a moving creation, in which we are immersed to the point of tears. “Happy is the man who has labored, he has found life” (Gospel of Thomas, logion 58): happy Ermine and Firmin, who, in sorrow, have found life through poetry.