When, in 1876, Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894) presented the painting which would be considered one of his masterpieces, “Parquet Planers”, the reception was mixed. We see, on a large canvas, three half-naked, sweating workers, busy on their knees in the middle of wood shavings. Faceless busts, absorbed in their work, the arrangement of the parquet floor of a plush apartment.

Some critics welcome the audacity. Others consider the subject “vulgar”, and these bodies, tested by effort, “ugly”, because they are far removed from the canons of ancient statuary. The shock is all the greater because Caillebotte chose to represent them in a tall and wide format, elevating this ordinary scene to the grandeur of a sacred painting.

“Parquet planers” (1875).

Orsay Museum, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

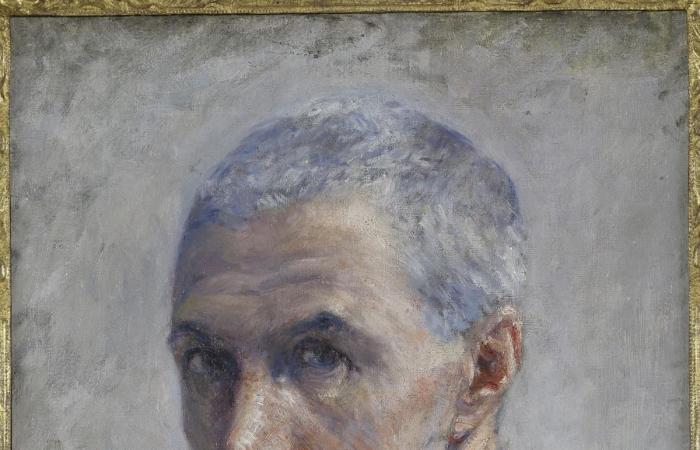

At the time, the painter, 28 years old, was still young. His work caused a sensation in some major exhibitions, he became more and more known, without being – and he would never be in his lifetime – fully recognized. His choice of themes perceived as trivial, innocuous, arouses resistance. Its slightly bizarre perspectives, its unexpected framing are disconcerting. This discreet boy, whose family made a fortune by supplying the army with sheets, is also pursued by a reputation as an heir who would paint in his spare time, without visceral commitment. However, he does not look like an idler. A self-portrait in 1892 reveals a severe, monastic face.

Grand-Palais/RMM (Musée d’Orsay) / Martine Beck-Coppola

Self-portrait (1892).

70% of the characters in Caillebotte’s works are male. Not heroes, but boys from his immediate environment

Long forgotten

He died at the age of 45, in 1894. Until the 1950s, his name remained on the fringes of the glory of the Impressionists. Worse, he is remembered above all for the collection of works he amassed, more than for his own paintings. The patron eclipses the artist. “He disappeared from memory for several decades, before his work was gradually rediscovered, then brought back to light through an exhibition at the Grand-Palais in 1994,” explains Paul Perrin, director of collections at the Musée d’Orsay. , and curator of the dazzling retrospective which has just opened (1).

Retrospective? The exhibition organizers are wary of this word, because their approach does not claim to be exhaustive. Out of 500 paintings by Caillebotte, the Musée d’Orsay presents a choice of 65 paintings. A selection guided by a common thread: the representation of men.

The curators noted that, a very unusual fact for 19th century painterse century, 70% of the characters in Caillebotte’s works are male. Not heroes at all, but boys from his immediate environment. Men of their time, who embody a new masculinity. They are workers, soldiers, dandies, athletes…

PAUL GETTY MUSEUM

“Young man at his window” (1876).

From realism to impressionism

The exhibition is organized into ten rooms. It begins with the family environment, then a parade of paintings dedicated successively to urban workers, sports enthusiasts, singles… Fifteen years of painting, and a fairly clear evolution, from the sharp realism of the beginnings to a more lively touch, more free, more impressionistic at the end.

Several nudes are gathered together. Men are shown in the privacy of their toilet, without any idealization, far from the perfect curves of Renaissance models for example.

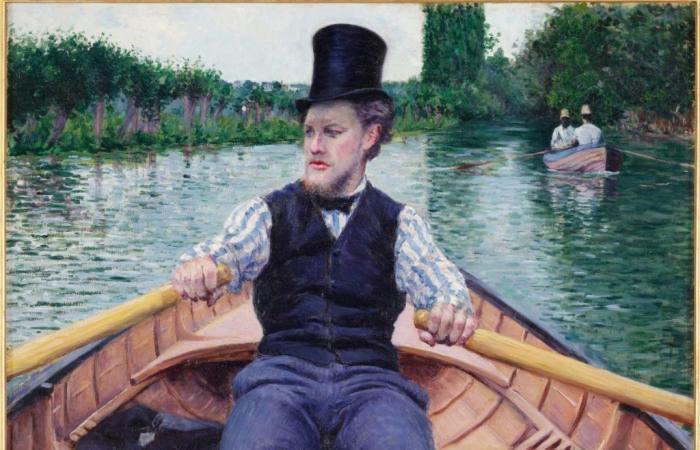

What does this tropism for the masculine say about Caillebotte’s work? The commissioners believe that the painter captured a moment of change in virility, weakened by the defeat of 1870 against Germany. His subjects appear pensive, absent, detached from a world that they observe from a balcony, a boat, or the metal viaducts overlooking the railway tracks.

Photo Josse / Bridgeman Images

“A balcony, boulevard Haussmann” (1880).

Private collection

“Canoeists rowing on the Yerres” (1877).

A question torments our curious and immodest minds during the visit, even if it seems that we must separate the man from the artist (who really believes that?): is this preference for male subjects the expression of a homosexuality of the painter? The exhibition answers neither yes nor no. “We do not seek to assert anything on this point, because we do not have documents allowing us to do so. We know factually that he was not married, that he had no children. But he lived with a partner, Charlotte Berthier,” notes Paul Perrin.

The mystery remains. The ambiguity is saved. Above all, we will remember that Caillebotte painted workers, bourgeois people, Paris in full transformation, a thousand scenes of daily life… The great movement of modernity.

(1) “Caillebotte, painting men”. At the Musée d’Orsay, in Paris. Until January 19, every day except Monday. From €11 to €16; free for under 18s. Late night Thursday evenings from 6 p.m., €12. Reservations recommended. More information on the website: www.musee-orsay.fr