the essential

A hundred years ago, on November 23, 1924, the ashes of Jean Jaurès were transferred to the Pantheon during a grandiose ceremony, commensurate with the place that the professor of philosophy, the socialist, the deputy, the tribune, the humanist. Yesterday in Toulouse, a tribute evening was organized in honor of the man who was also a child of Occitanie.

At each ceremony of pantheonization of personalities – the resistance fighters Pierre Brossolette, Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, Germaine Tillion and Jean Zay in 2015, Simone and Antoine Veil in 2018, Maurice Genevoix in 2020, Joséphine Baker the following year, Mélinée and Missak Manouchian this year – we are always overcome with emotion when the coffins go up rue Soufflot towards this republican temple dedicated to Great Men – and Great Women. This ceremonial seems to complete the destiny of those we honor and also enters, sometimes, for itself into the History of France. This was the case for Jean Moulin, whose ceremony on December 19, 1964, remains marked by André Malraux's peroration for the leader of the Resistance. This was also the case for Jean Jaurès forty years earlier. Today, we celebrate the centenary of this pantheonization, the scale of which is difficult to imagine.

Differences with the Communists

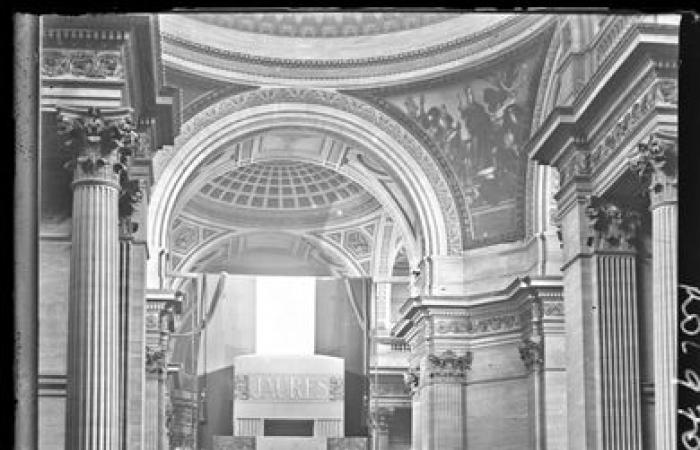

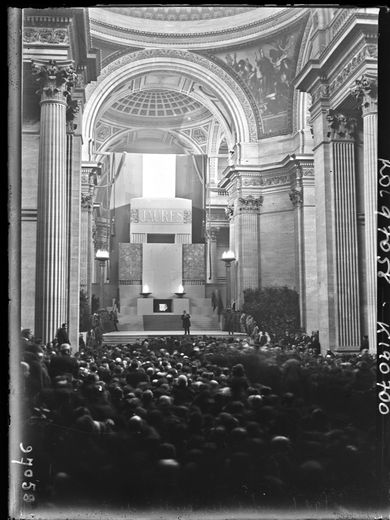

Photos of the event, November 23, 1924, are rare, but the ceremony, which goes beyond what one could imagine, was carefully reported in the press and obviously by La Dépêche in which Jaurès signed so many articles and editorials.

DDM

If the pantheonization of the deputy from Tarn – an apostle of peace who tried to prevent the outbreak of the First World War until the cost of his life on July 31, 1914 – seems obvious today, it nevertheless gave rise to lively controversies at the time. In 1924, the ruling Left Cartel saw the 10th anniversary of the tribune's death as an opportunity to offer itself a symbol by having him enter the Pantheon. It doesn't matter that Jaurès once told Aristide Briand of his wish to be buried in “one of our little sunny and flowery country cemeteries”, rather than in a sinister vault in the Pantheon, the decision is made… and divides the left . The Communists are furious and cry for recovery. In L'Humanité of November 23, Paul Vaillant-Couturier wrote a scathing article denouncing “The second assassination of Jaurès”. “Jaurès, who fell into the service of a proletariat which wanted peace, does not belong any more to Mr. Renaudel than to Herriot. By his legend and by his death, it is to the Revolution that he belongs,” he wrote, calling out to the miners of Carmaux and Albi who were to carry the coffin.

MaxPPP.

The Dispatch of November 24 recounts how the Communists, who decided to follow an alternative route to that of the official procession, distributed leaflets in the working-class neighborhoods of Paris and the suburban working-class communities to hammer home that “the supporters of the Left Bloc will not can only outrage the memory of Jaurès. » The other false note comes from the Royalists who had multiplied the hostile posters.

The emotion of the Carmaux miners

What does it matter, here too, in the face of a ceremony expected, especially by the minors. “On arriving at the Chamber, we met miners from Carmaux. We are chatting with one of them,” wrote La Dépêche, the funeral wake taking place at the National Assembly. “I will never forget this day,” he told us. If you only knew how proud we are to carry the ashes of Jaurès. — Did you know him? — Everyone who is here knew and loved him. He often came to see us at the mine. And the man then gravely pronounces these words, in the beautiful dialect of the southern lands: Ero not a defender for us oppressed, ero a friend. This is how the miner from Carmaux spoke to us. It was he who expressed the feelings of the immense crowd…”

DDM

“Those who were able to follow the various phases of this pathetic, simple and grandiose ceremony from start to finish will keep an indelible memory of it. The tribute that the people of Paris have just paid to Jaurès has, in fact, exceeded anything we could have imagined,” writes Jacques Bonhomme in La Dépêche.

“The vigil first, all meditation and contained emotion. When the coffin, draped in black and purple, is seized by its nine bearers, only friends of the first degree and official figures are there to receive it, as it were, from the hands of the Carmaux miners whom Jaurès loved so much and who, until the end, will mount a faithful, almost fierce guard around his remains. They do not yet abandon him to the crowd and to the immortality which is henceforth his destiny; it's a family ceremony. But the people of Paris are there waiting for him, on the neighboring quay. When the coffin appears, with its magnificent escort of flowers, a huge cheer rings out: “Long live Jaurès!” » The same one who greeted his corpse one evening when he was murdered. It is the solemn affirmation that a man like this cannot die, since he will live forever in the hearts of men. »

“Long live Jaurès, long live peace, long live Herriot”

After the vigil at the Palais Bourbon, the coffin begins its journey towards the Pantheon, whose dome disappears in the mist, passing through an immense crowd including socialists, radicals and republicans, who greet the procession with “Long live Jaurès, long live peace, long live Herriot.”

MaxPPP.

“Here we are in front of the catafalque of the Pantheon illuminated by bronze torches and where the name of the deceased stands out in gold letters. Outside the crowd is silent, contemplating the statue of the tribune who seems to be addressing him with a supreme harangue. […] The ceremony is over. Jaurès will sleep his last sleep, in the Temple of Glory, next to this Normal School where his brain and his heart were shaped, in the center of the City of Lights of which his genius remains one of the torches. »