- Migrant workers in Saudi Arabia face widespread abuse, some amounting to forced labor, in all employment sectors and regions, including in the context of high-profile “gigaprojects” financed by the sovereign wealth fund. of or linked to Saudi Arabia.

- FIFA, the international Football federation, is expected to soon confirm that Saudi Arabia will host the 2034 men’s World Cup, but has not demanded that the country demonstrate due diligence on rights issues or commit in a binding manner to prevent violations of workers’ rights.

- Saudi authorities are systematically failing in their duty to protect migrant workers from the risk of serious abuse. It would be urgent to remedy the insufficient application of Saudi laws supposed to protect immigrant workers; laws which, moreover, meet neither international standards nor the country’s obligations arising from international human rights instruments.

(Beirut, December 4, 2024) – Migrant workers in Saudi Arabia face widespread violations of their rights, in all employment sectors and all regions, including in the context of high-profile “gigaprojects” financed by the sovereign wealth fund. of or linked to Saudi Arabia, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) plans to confirm on December 11 that Saudi Arabia will host the 2034 Men’s World Cup; However, FIFA has not required this country to demonstrate due diligence on human rights, nor to make a binding commitment to prevent violations, including of workers’ rights.

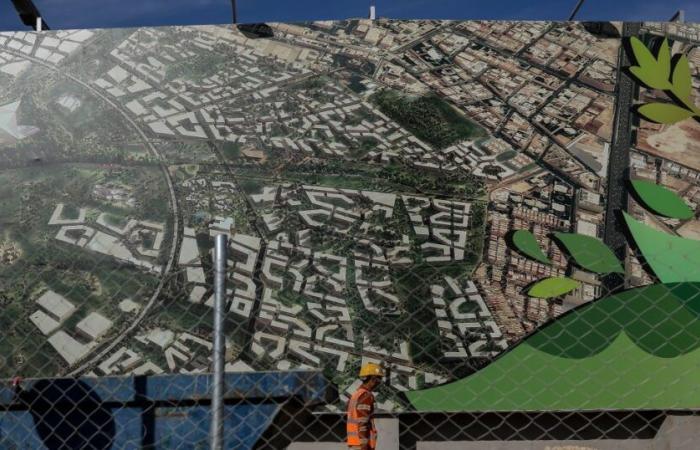

The 79-page report, titled “‘Die First, and I’ll Pay You Later’: Saudi Arabia’s “Giga-Projects” Built on Widespread Labor Abuses.” Saudi Arabia’s gigaprojects are built on systematic violations of workers’ rights), describes widespread abuses committed against migrant workers, which in some cases could amount to forced labor. These abuses include exorbitant recruitment fees, frequent wage theft, insufficient protection against heatwaves, difficulties in changing employers and uninvestigated worker deaths. Saudi authorities have systematically failed in their duty to prevent or mitigate these abuses, including those committed under the country’s sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (Public Investment Fund, PIF).

« The human machinery that allows Saudi Arabia to build multibillion-dollar gigaprojects is immigrant labor, whose rights are widely violated in the country, with no possible recourse. said Michael Page, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “ The evaluation process FIFA’s bogus decision to award the 2034 World Cup without any legally binding human rights commitments will have an unimaginable human cost, including terrible impacts on migrant workers and their families of all generations. »

The report is based on interviews with more than 155 migrant workers, currently employed, or formerly employed, across several sectors and regions in Saudi Arabia, as well as relatives of deceased workers.

Migrant workers coming to Saudi Arabia face labor rights violations at every stage of the immigration cycle, Human Rights Watch found. The abuse begins when companies recruit workers and force them to illegally pay exorbitant recruitment fees. They continue when Saudi employers violate their employment contract by not respecting the conditions of employment and the benefits it provides.

« I was paid for the first two months, then nothing more “, testified a migrant worker. When I asked my manager for my salary, he replied: “ Die first, then I’ll pay you. »

Despite Saudi Arabia’s labor code reform initiative launched in 2021, which purported to make it easier for migrant workers to change employers or freely leave the country, they still face obstacles to mobility, which abusive employers exploit for their profit.

« I was advised to obtain departure permission, leave the country and migrate again to work with another company “, said a worker. “ More [mon employeur] answered me: ‘If we let you change your sponsorship, we would also have to allow everyone else to do so.’ »

Other employers force workers to sign an agreement where they agree to pay a sum to the employer in case they leave to take another job. Thus workers who had managed to change jobs were forced to pay their former employer. A worker employed at a NEOM construction site – a PIF-funded gigaproject being built in northwestern Saudi Arabia – said he had paid more than 12,000 Saudi riyals (approximately 3,200 US dollars) to his ex-employer to be able to work elsewhere.

Additionally, many migrant workers lack the information and IT skills needed to master online employment contract management services. Faced with the intricacies of the Saudi labor code, they have difficulty understanding what their rights are; and cannot seek help from the Saudi authorities or the embassy of their country of origin.

Gigaprojects often impose very tight, even unrealistic, site delivery dates, which increases the pressures placed on workers. Additionally, many workers are isolated from support networks such as embassies or well-established expatriate associations. A worker working on a NEOM project site commented: “ We are in the middle of nowhere. Our embassies are very far away. If something happens to us, we have nowhere to go. We are afraid, too. Where to contact us? Who to talk to? »

Nearly 13.4 million migrant workers are currently in Saudi Arabia; this number is expected to increase significantly with the planning of new megaprojects, or even gigaprojects, which will require massive construction sites.

Employers also expose their workers to serious dangers in their workplace, in particular because of the extreme heat that workers on outdoor sites experience – heatwaves which are likely to increase with the acceleration of climate change. A worker employed on a NEOM site testified: “ Every day, one or two workers faint, even in the morning or evening. Sometimes it’s on the way to work. Sometimes it’s during work. » Extreme heat abuse can cause migrant workers to suffer long-lasting and potentially lethal health problems, including organ failure.

According to government data obtained by Human Rights Watch, 884 Bangladeshis died in Saudi Arabia between January and July 2024, with 80% of deaths attributed to “natural causes.” Many deaths of migrant workers in Saudi Arabia remain unexplained, uninvestigated and uncompensated, leaving families without any financial support.

The wife of a deceased Indian plumber told Human Rights Watch: “ He had no health problems. We do not believe he died of natural causes as stated on the death certificate. No one seriously investigated his death. » And to continue: “ He sent around US$536 each month to cover family expenses, school fees and ongoing repayments. With his disappearance, we find ourselves destitute. »

Human Rights Watch also spoke with seven former migrant workers formerly employed in Saudi Arabia who are now on dialysis due to acute kidney failure. The wife of one of them told Human Rights Watch that while her husband’s dialysis was paid for by the Nepalese government, she had no money to pay for his medication or his school fees. their children, for six months. She testified: “ The company [saoudienne] provided no assistance other than booking a plane ticket for him [pour rentrer chez lui]. »

Although it is the Saudi authorities that have the primary obligation to protect human rights, including workers’ rights, businesses also have an internationally recognized responsibility to respect human rights and avoid being complicit of abuse. There is an urgent need to address the pervasive failure to enforce Saudi laws that are supposed to protect migrant workers. However, as this report demonstrates, while it is essential to combat non-compliance with the law, it would not be sufficient in the context of Saudi Arabia, where many laws, on their own, do not meet neither international standards nor the country’s obligations under international human rights instruments, Human Rights Watch said.

Saudi Arabia’s proposal to FIFA to host the 2034 Men’s World Cup failed to adequately address widespread human rights violations in the country. Despite massive construction needs, including eleven new stadiums and the renovation of four other stadiums, more than 185,000 new hotel rooms, as well as a major expansion of the network of airports, roads, buses and railway lines, this proposal does not provide any concrete guarantee that these abuses will be resolved.

FIFA designed the World Cup award process to turn a blind eye to glaring signs of human rights risks, such as the forced labor complaint against Saudi Arabia that the International Workers’ Federation of Building and Wood (IBB, or BWI in English) filed with the International Labor Organization (ILO) in 2024.

Human Rights Watch wrote to FIFA on November 4 with its findings and documentation of serious and widespread violations of workers’ rights related to Saudi mega- and giga-projects, but received no response. day.

« The Saudi authorities, who are spending billions of dollars to whitewash their abominable human rights reputation, would do better to finally actually implement their long-promised labor law reforms », a conclu Michael Page.