In Morocco, school is constantly questioned about its role within society, it is even identified as the reason for the societal crisis. Reformed numerous times since independence in 1956, the education sector remains far removed from contemporary economic and social issues. Therefore, the teaching profession does not hesitate to mobilize as soon as the authorities intend to apply measures without real effects, as at the start of the 2023-2024 school year, when new forms of protests appeared.

Lhe Moroccan school has undergone several reforms, starting with the introduction in the 1960s of four main principles: unification, Arabization, Moroccanization and generalization (1). The process was finalized two decades later by Azzeddine Laraki (1929-2010), Prime Minister from 1986 to 1992: French, then learned only as a foreign language, remained the language of teaching in the faculties of science, medicine, engineering, which is still the case today. A new reform began in the 1990s: it recommended the creation of a Royal Advisory Committee on Education and Training. The latter prepared a National Charter in 1999, which experienced several dysfunctions leading to the adoption of the emergency program between 2009 and 2012 which, in turn, did not meet societal expectations. The Higher Education Council was reorganized in 2014, renamed the Higher Council for Education, Reform and Scientific Research. On May 20, 2015, King Mohamed VI (since 1999) chaired the presentation ceremony of the Strategic Vision for school reform (2015-2030) at the Casablanca Palace: for a school of equity, quality and promotion.

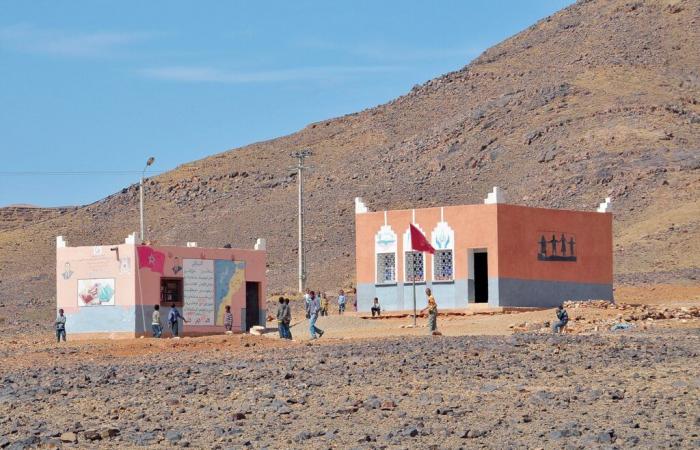

Ethnography of a disconnected and failing school system

The succession of these changes has produced a perverse effect, without leading to an effective model. Thus, from the end of the 1990s, the private player invested in the education market, to now represent more than 35% of educational establishments. All these reforms show to what extent the system is in crisis, and that it is struggling to give school a definition and a meaning to its role within society. The reforms take a more political than educational turn. Moreover, the “Vision 2015-2030” occurs in a context where three elements interact: social pressure on the school, a change of Constitution in 2011 and an evaluation of the application of the National Charter implemented in 2000 to 2013. These reforms did not touch on the question of the forms and manners of learning as a central point nor on the context in which formal knowledge is transmitted; it remains abstract, not connecting the individual to society.

In 2019, the state commissioned an ethnographic study on classroom learning. It aimed to identify the limits of the construction of knowledge (and know-how) between the different actors concerned – teachers, learners, peer groups, the school environment, etc. – in three regions (Tangier- Tétouan-Al-Hoceïma, Fès-Meknes, Drâa-Tafilalet). After several visits to around thirty schools, the main findings are: a great weakness in academic achievement, linguistic inconsistency, a teaching difficulty, a flagrant deficit with regard to teacher training, unfavorable working conditions, a altered image of the school and therefore of the teacher among learners and their tutors. In the context of the transformations that the educational system in Morocco has gone through, it is possible to say that the pedagogical approaches of the Moroccan school have as their main objective the transmission of content through the almost mechanical memorization of the rules; the exercises being only means of recovering the information retained. The teacher is the only legitimate and unique possessor of knowledge. The student is perceived as a passive individual, supposed to be a simple receiver of information; he is not recognized as having any skills. In this context, physical violence becomes legitimate, even operational and utilitarian, because it “facilitates” class control.

The teacher must manage time, plan lessons, present them, prepare the tools necessary for them, establish order, mark absences, clean the room and toilets (if they exist), lead activities, etc. . Time is not organized as a means of supporting students in their learning. The structuring of lessons and the time allocated to each subject do not allow teachers to respect the children’s pace. The result is a lack of richness, diversity and interaction.