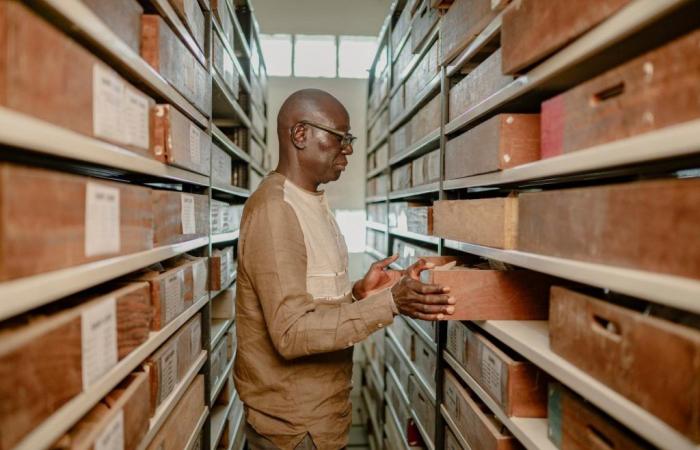

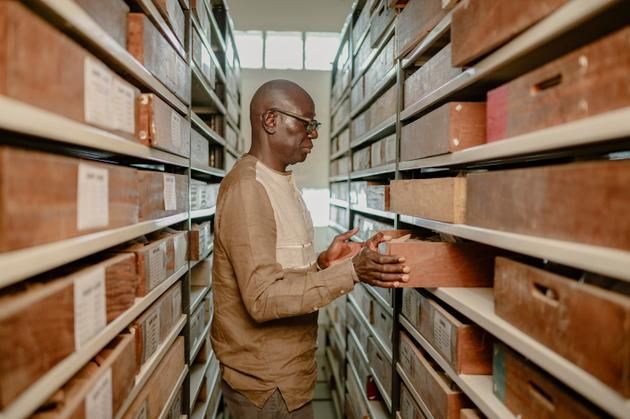

In a dark room at Cheikh-Anta-Diop University in Dakar, large shelves rise to the ceiling, on which dusty drawers eaten by termites are stacked. They are filled with pebbles, flint and pottery from Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Senegal. In front sits a pile of crates with holes and rusty iron trunks. “In this reserve are the oldest collections of the Fundamental Institute of Black Africa [IFAN]collected even before the country’s independence, in 1960 »indicates Professor Ibrahima Thiaw, one of the first Senegalese archaeologists to be interested in the transatlantic slave trade, between the 15the and the 19the century. IFAN was created in 1936, when Dakar was the capital of French West Africa.

Upstairs, in an air-conditioned room, objects from the island of Gorée, located off the coast of Dakar and symbol of the triangular slave trade, are stored in more modern storage cabinets. In front of them, piles of boxes collapse. “European colleagues dug up objects to study them. This allowed them to publish prestigious scientific articles. And afterwards, they left us trunks of objects that were difficult to keep.”, deplores Ibrahima Thiaw, who directs the research unit in cultural engineering and anthropology (Urica), created in 2017, and which is part of a decolonial approach. This approach – also present in other disciplines such as sociology or anthropology – is distinguished by a desire to break with the practices and analytical grids inherited from colonization.

“Some teams continue to act as if we are still in colonial times”he regrets. The archaeologist would like Western scientists to further integrate the preservation of heritage and the training of students in its conservation in their research budgets on the African continent.

In the Urica rooms, around ten students are working on their computers. On the walls, the faces of Aline Sitoé Diatta (1920-1944), heroine of the Senegalese resistance against French colonization, and Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), American abolitionist, were painted by the pan-African graffiti collective RBS Crew.

Lamine Badji, doctoral student in archaeology, looks at skulls griots, these storytellers who orally transmit the history of their country. These human remains were recovered from baobab trees by a Belgian anthropologist in 1965. Until this practice was banned by President Léopold Sédar Senghor in 1962, griots were not buried in cemeteries with other inhabitants, but inside the trunk of one of these sacred West African trees. “The objective is to “decolonize” this collection by resuming its study from a Senegalese prism, that is to say by ensuring that we respect our beliefs and traditions. We must first obtain the consent of the families because the ethical question of their scientific exploitation arises”explains the doctoral student.

“Other human remains collected in Senegal were left without conservation monitoring, they are now rotten and contaminated by bacteria. Where is the respect? This would never have happened in Europe. Black bodies are not inferior to other bodies”protests the Senegalese researcher, who strives to restore dignity to these human remains. He took DNA from the skulls of these griots to try to identify their descendants. “We were able to trace some of them in America, which proves that descendants of griots were sent as slaves across the Atlantic, although writings claim that they were spared”explains Mr. Badji.

“Restorative dimension”

Respect for human beings and relationships with communities are at the heart of the work that Ibrahima Thiaw wishes to promote. “The body is not an object but a soul, and its history is linked to the living”continues the professor. “The deep wounds that this tragedy has left in today’s society must be taken into account. We cannot ignore this emotional aspect. The restorative dimension of archaeology, which allows us to reweave the thread of family stories broken by separation and exile, is too neglected. »

The Senegalese scientist focused his research on the island of Gorée, where he studied the impact of the slave trade on modern West African societies. A work which allowed him to rewrite the history of this island, from the point of view of the victims, whereas until then it had been told through the Western perspective.

“The historiography of coloniality is imposed through writing, which is fetishized. Even if it does not necessarily correspond to what happened, the challenge is to explore parts of this story that have been kept quiet.explains Professor Thiaw. Archeology allows us to compare what is written in texts with what was left by material traces..

The archaeologist was, for example, struck by the few European objects prior to the 18th century.e century found on the island of Gorée, while the texts document their presence – and even their hegemony – from the 15the century. “We mainly found European objects from everyday life such as inkwells, alcohol bottles, or weights for weighing precious objects, which date from the 18th century.e century “underlines Mr. Thiaw.

There is no shortage of questions. Despite texts on the atrocity of the slave trade, the archaeologist has so far only discovered a single handcuff, alongside firearms and flints.

Follow us on WhatsApp

Stay informed

Receive the essential African news on WhatsApp with the “Monde Afrique” channel

Join

To broaden their field of research, Professor Thiaw and his students have been exploring the seabed for ten years with a view to mapping the wrecks of European ships. They form the first maritime archeology team in West Africa led by Africans. Young archaeologists dived off the coast of Gorée Island for a month, between May and June, to obtain acoustic images at the sites of two wrecks, probably linked to the slave trade. One of them dates from the beginning of the 19th century.e century.

“Total disaster”

“The hull of the wreck is covered with a copper alloy which was used at the time to protect ships from the Atlantic trade from warm waters and from micro-organisms which attack wood”explains Madicke Gueye, doctor in underwater archaeology. He is the national coordinator of the Slave Wrecks Project, a project dedicated to the wrecks of slave ships between Senegal, Mozambique and South Africa. “The inventory work undertaken over the past ten years has allowed us to identify 24 underwater archaeological sites off the coast of Gorée. We now need to be able to date them”he adds.

Until then, only a few dives had been conducted, in 1988, by the French underwater archaeologist Max Guérout. “It was a total disaster. The artifacts that were taken out of the water were very poorly preserved”deplores Ibrahima Thiaw. The archaeological pieces of these underwater expeditions are, in fact, still stored in buckets of salt water at the Gorée historical museum.

Read also | These five memorial files which persist between France and Africa

Add to your selections

The underwater remains have spent centuries submerged, sheltered from light, in a salty and oxygen-poor environment. Fragile, they must be subject to appropriate treatment. “We lost a good part of this collection, especially all the wooden objects”regrets Madicke Gueye. The young researcher is campaigning for the opening of a conservation laboratory which would make it possible to safely extract the remains still buried in the depths of the Atlantic and finally reveal their secrets.