Respected curator, recognized artist: for Paolo Colombo, the secret lies in clearly distinguishing one from the other.

2010 Venturelli

Director of the Center for Contemporary Art in Geneva between 1990 and 2001, Paolo Colombo returned there as an artist. His exhibition entitled The Second Time is a retrospective which celebrates half a century of this cultural center. Exactly what the career of this visual artist and poet has lasted so far.

This content was published on

January 5, 2025 – 08:00

Paolo Colombo (Turin, 1949) interrupted his artistic activity for twenty years to devote himself to his family and to various museums and artistic institutions. An experience that made him understand the world of art from this dual point of view. A graduate of language and literature at the University of Rome, Paolo Colombo is also a poet.

Just like his poetry, his art lives in close connection with the rhythms of everyday life and inner thought. Resident in Crans-Montana, in Valais, he has his workshop in Athens, which he considers ideal for living his art and a simple lifestyle in symbiosis.

The name of Paolo Colombo is closely linked to the Geneva Contemporary Art Center. His return has all the makings of a symbol, especially since it helped to forge the place occupied by this institution on the European artistic scene. Among the works on display are watercolors, some accompanied by poetic texts, multimedia works and extracts from some of his books. We also discover collaborations combining contemporary art and traditional crafts. Like this rug made in India adorned with embroidery made in collaboration with to repeat.

Covering the period 1971-2024, the forty selected works refer to existence and beauty, offering the public a reflection on cultural heritage and the regenerative power of art. The exhibition is on view until March 2, 2025.

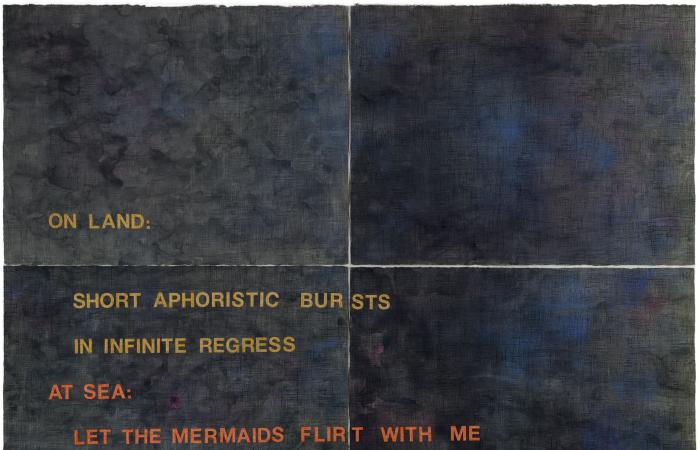

Paolo Colombo, On land, 2021.

2020 Photography Boris Kirpotin / Courtesy Bernier-Eliades Gallery

swissinfo.ch: How was your return to the Center for Contemporary Art as an artist?

Paolo Colombo: It’s a return that moves me deeply. I exhibited in this center for the first time in 1978, under the direction of Adelina Von Fürstenberg. When I left, the institution was still young, with a reduced budget. I find it in full maturity, with retrospectives of leading artists and a fantastic Biennial of the Moving Image. Its reputation has been strengthened also thanks to its current director Andrea Bellini. I am very happy to benefit as an artist from the progress of the center and to be able to celebrate it.

During your tenure, you worked with limited resources. A context of “institutional poverty”, as you describe it. And this, despite the wealth of the city. How did you go about growing the center?

The contrast between the wealth of Geneva and the weakness of the resources allocated to contemporary art has always struck me. I had to develop an inventive attitude, which stems from my childhood. As a child, I imagined being able to put together an orchestra with people playing with rubber bands. And in my leadership work, I have made this idea a reality. A “creative sobriety” which is also reflected in my artistic work. To extend the metaphor, I have been the director of an orchestra of rubber bands throughout my life, in different roles.

Paolo Colombo, Wisteria (detail), 2023.

Made available by the artist and Baert Gallery

You have been a curator in difficult contexts, such as that of the Mardin Biennale (Türkiye). What have you learned from these projects?

When I organized the Mardin Biennale in 2012, I had a budget of only thirty thousand dollars. The Biennale was called Double Take. It was one of my most formative experiences: I placed works in cafes and public spaces, where the line between art and everyday life blurs. It taught me that art can stand alone and not depend on context. If a work really works, it has the ability to be perceived by everyone, even in an unconventional environment.

Let’s come to your life as an artist. Between your exhibition in Milan in 1974 and now, fifty years have passed. What has changed in your artistic approach? And what has always accompanied it in reverse?

I took a 21-year hiatus from working as an artist. I don’t think it’s possible to be a Sunday painter. The profession of curator was my greatest school. I learned a lot about spaces, but I don’t have the perspective to discern an influence of curation on my artistic work. Poetry like painting gives me a feeling of ecstasy which matches the essentiality and sobriety of my art. I started with pencil and paper, creating art that I could roll up and slide into a shoe box. This sense of sobriety is a common thread that runs through me and persists in my work. Even today, for example, I make videos with my cell phone and materials found on the beach.

In your work, time seems to count more than material elements. Is this a correct reading?

Absolutely. My works reflect a meditative, almost ritualistic approach, if you think that I repeat this same gesture of dipping a brush in water to clean it 100 to 120,000 times for a single painting. There is a kind of self-hypnosis in painting, in creating each element of the mosaic or in tracing a line, a point or a mosaic tile. For me, the time invested in a work is tangible.

You are a happy resident of Crans-Montana, but your studio is in Athens. How does Greece influence your work?

Greece is my inexhaustible source of inspiration. It is the land of joy, of music that I have listened to all my life and of the poems of George Seféris and Kaváfis, which I still read. Byzantine art, abstract and non-mimetic, has always had a great influence on me. In Athens, I have a shamefully wonderful life, the city offers me the rhythm and concentration necessary to work, in a context where I can live and create at my own pace, interspersing work with simple pleasures like feeding the street cats . A simplicity that I also experienced as a child in the Swiss Alps.

What would you like the public to take away from your work?

I paint what I like, what I find beautiful, without worrying about whether it pleases or not. Greek musicians from the 1920s to 1950s, for example. I hope the public realizes the time and soul I devote to my works, the serenity and care. Each work is the result of gestures repeated a thousand times. It is a way of living in balance with the world. I hope that each viewer will find something universal in my work.

In your opinion, should art play a political role, challenging cultural divides and stereotypes?

I never think about it. I always have in mind a limited dimension, a 1:1 ratio with the work, a book for example. My work is in no way an assessment of what is happening in the world. For me, art is about authenticity and humanity more than politics. Sobriety and sincerity can have a force that goes beyond cultural patterns.

What do you hope for the center which is about to close its doors for at least three years for renovation?

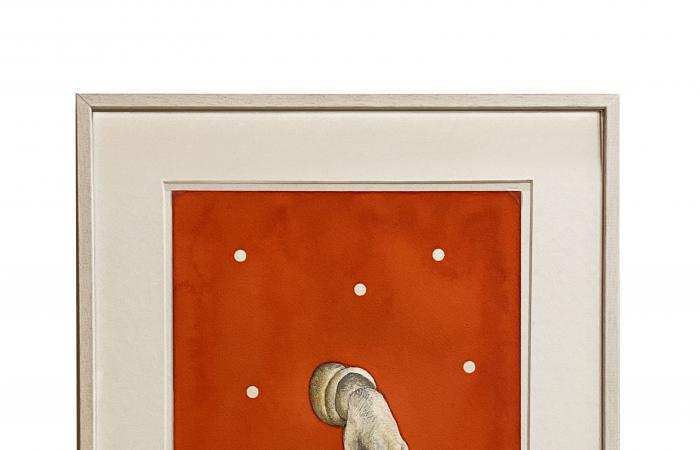

Paolo Colombo, Aphrodite’s Hand, 2021.

Made available by the artist, private collection, Paris.

I hope it will retain some historic elements, like the wooden block flooring, which dampens sounds and vibrations. After fifty years, it is natural for a place to renew itself. I am convinced that Bellini is making the right choices for the times, respecting the identity of the center and continuing to project it towards an international future that is in no way paternalistic.

This temporary closure with the exhibition Rituals of Care by the Brazilian artist Antonio Obá (1983) does it go in the direction of breaking with an often stereotypical vision of what is expected from non-European artists?

Certainly, it takes me back thirty years and more, when I put together an exhibition with Brazilian artists like Jac Leirner and visual poets Augusto and Haroldo de Campos. At the time, it was not at all easy to organize an exhibition where non-European artists were not placed in predefined and limiting categories. Fortunately, this is no longer the case.

Proofread and verified by Daniele Mariani/translated from Italian by Pierre-François Besson

Learn more

Following

Previous

Plus

Switzerland, Dada and a hundred years of surrealism

This content was published on

June 30. 2024

Why did Dadaism practically disappear from Switzerland after its launch in Zurich in 1916? The analysis of art historian and exhibition curator Juri Steiner.

read more Switzerland, Dada and a hundred years of surrealism

Plus

Switzerland in superfiction at the Venice Biennale

This content was published on

May 10. 2024

Swiss-Brazilian artist Guerreiro do Divino Amor represents Switzerland at the 60th edition of the Venice Art Biennale, which opened on April 20. Encounter.

read more Switzerland in superfiction at the Venice Biennale