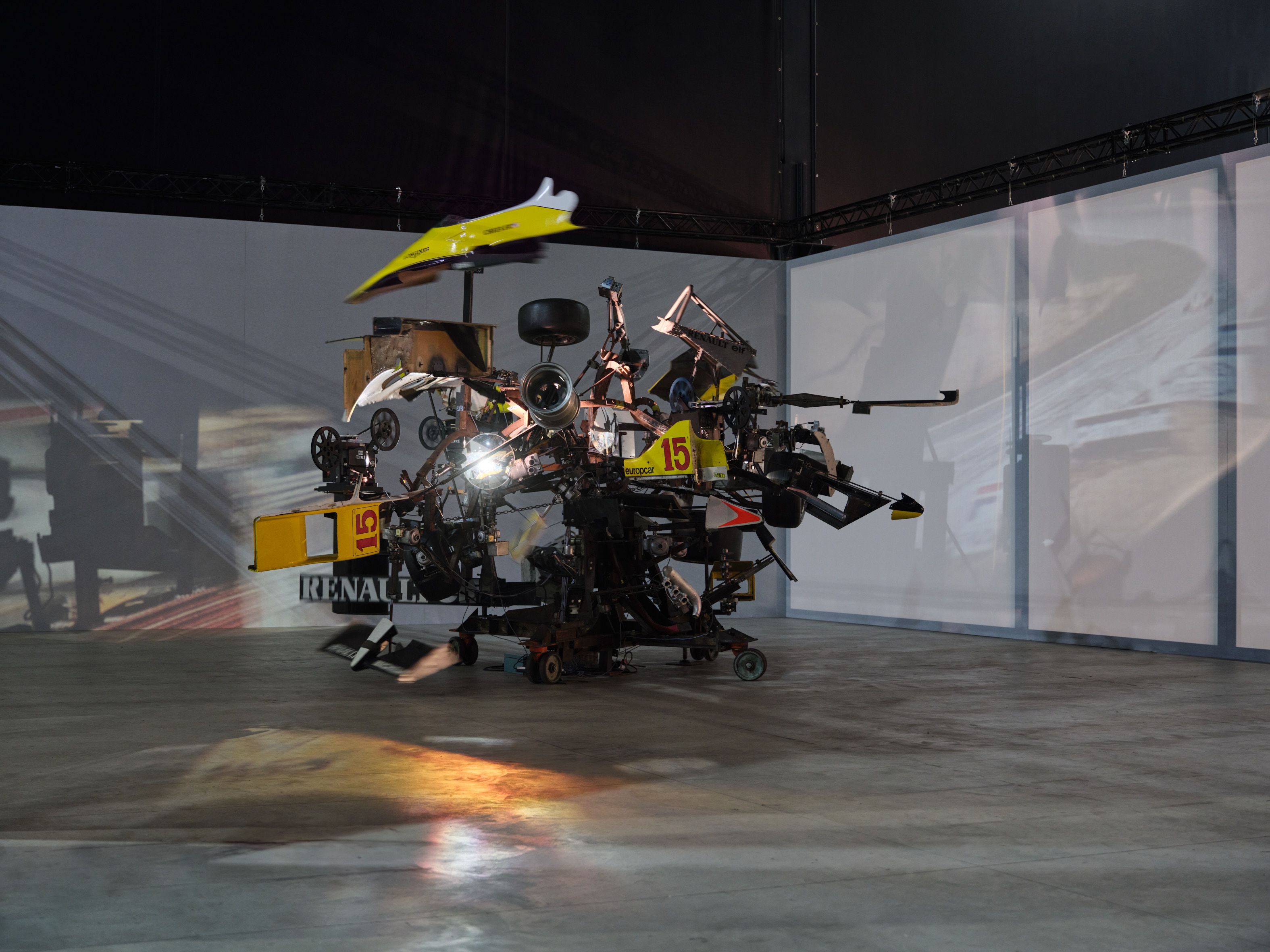

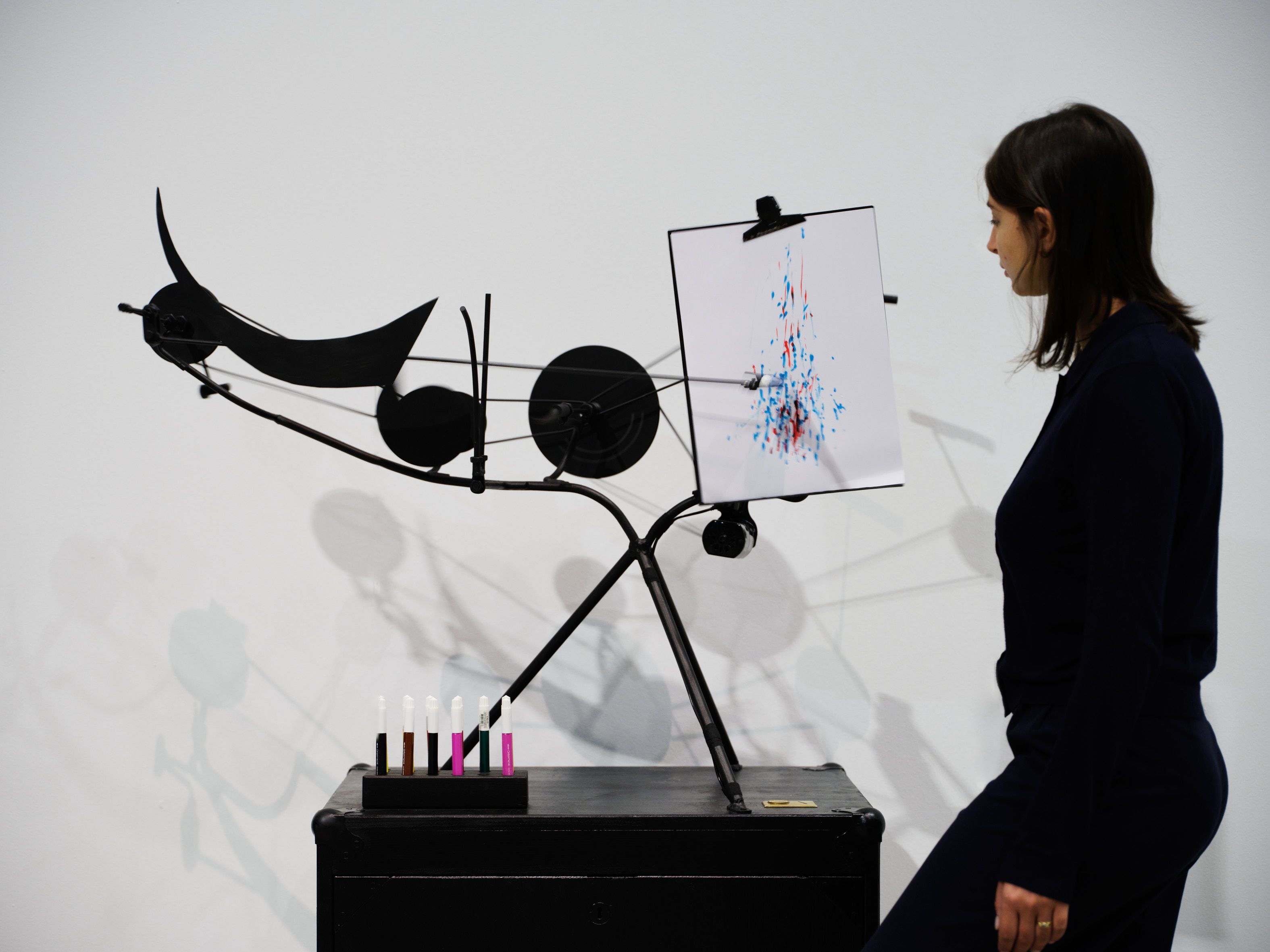

“Méta-Maxi” (1986), work by Jean Tinguely exhibited at Hangar Bicocca, Milan.

Alto Piano Srl

A major exhibition at the Hangar Bicocca, in Milan, opens the celebrations of the centenary of the birth of Jean Tinguely (1925-1991). The selection of 40 sculptures, created between the 1950s and 1990s, reinforces his reputation as a pioneer of kinetic art.

This content was published on

December 28, 2024 – 09:00

Jean Tinguely was just a child at the time when the old Hangar Bicocca was an essential cog in Mussolini’s war effort. The hangar was then a factory for parts for cast iron locomotives, aircraft and military equipment. The foundry continued to exist until 1986, when it was transformed into a cultural center.

The Milan exhibitionExternal link marks the end of a cycle in Tinguely’s international career. It was here that in 1954, the young artist participated in an exhibition at the invitation of Bruno Munari (1907-1998), one of the creators of programmed and kinetic art. Tinguely’s contribution to the “Tricycle” collection (1954) is part of the Milan retrospective.

The post-war economic boom was then in its early stages and the consumer society was in full emergence. The enormous quantities of waste from industrial production were just waiting to be resurrected. Tinguely saw in all this abandoned scrap metal a raw material for his kinetic sculptures.

“The machine is above all the instrument that allows me to be poetic,” said the artist. Trains, cars, motorcycles, bicycles, toys and household appliances were conquering the streets and homes. These great innovations full of mechanisms, although packaged in beautiful boxes, would sooner or later end up in the trash.

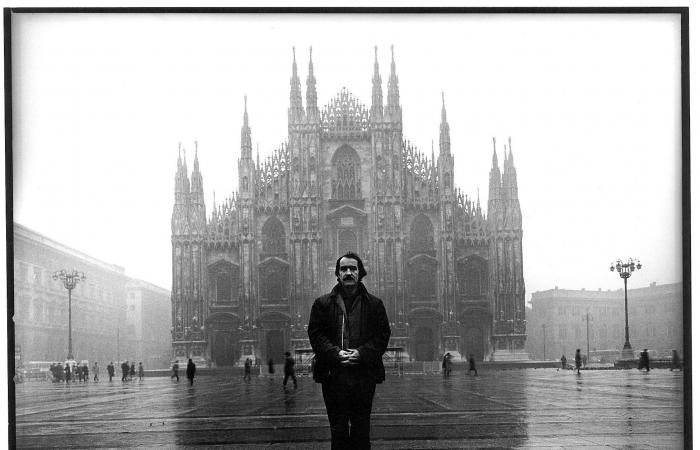

Tinguely in front of the Duomo, Milan Cathedral, November 1971.

© SZ Photo / Wolleh Lothar / Bridgeman Images

Playful art

Jean Tinguely observed and studied the assembly lines before finally dismantling them. He extended the useful life of objects by giving them an amusing inanity: dismantled and sculpted, vertically or horizontally, they no longer had any link with their original function. Wrecks of agricultural machines, grinders, drills, even pot lids still have shark teeth have thus acquired a new uselessness.

The artist subverted the industrial project by imagining new forms and new functions, almost always useless and therefore tragicomic, but always provocative. Thus this pioneer of kinetic art became one of the major figures of New Realism, a movement which favored the use of used materials.

Artists with the idea of recycling scrap materials were still rare at the time. One of them, the American Richard Stankewicz (1922-1986), inspired Tinguely with his static works made of reused metals. Tinguely discovered his work in 1948; it was this spark that ignited the imagination of the artist, who had already made a small motorized object to hang from the ceiling. In honor of Stankewicz, Tinguely built and then destroyed his famous Homage to New York in the MoMA garden in 1960.

“The effect of ephemeral surprise was an integral part of the machines built by Tinguely. There wasn’t a lot of planning, everything was put together in the moment,” explained Lucia Pesapane, co-curator of the retrospective, at the opening of the exhibition in Milan. “And it amused him a lot when it didn’t work. For him, this element of improvisation and rupture in his works was a reflection of the ‘real life’ that we must accept. The more his devices exploded and self-destructed, the more the truth was reached.”

Jean Tinguely poses in the Swiss Bruno Bischofberger gallery in Zurich, in September 1979.

KEYSTONE/PHOTOPRESS-ARCHIV/Str

Secrets d’assemblage

Even before eliciting interpretations from the public, the complexity of Tinguely’s machines challenges the people who must assemble them. According to Lucia Pesapane, there is an additional characteristic of the artist: nothing can be left to chance.

“Transporting, assembling and dismantling Tinguely’s works is a monumental job, imagined and implemented down to the smallest detail by the artist himself, and almost always without instructions,” explains Lucia Pesapane. Unlike today, market logic did not yet reign on the art circuit in the 1960s, she recalls. “Tinguely was rather happy that his works were destroyed and was not concerned about their conservation. And that adds to the difficulty of putting together this exhibition, which extends from the beginning of his career to the end of his life in the early 1990s,” she says.

Half of the works in the retrospective come from the Tinguely MuseumExternal link in Basel and the other half from museums in Germany, France, the Netherlands and private collections. Preparing the exhibition took almost two years. Each work has its own box, but 10 or 15 are needed for the most monumental ones. “The logistical complexity adds to the fascination of seeing them here,” emphasizes Lucia Pesapane.

Would you like to receive a selection of our best articles of the week by email every Monday? Our newsletter is made for you.

Adult childhood

The Swiss artist’s works are imbued with curiosity and creativity, reminiscent of the world of childhood. On the one hand, his sculptures are playful in essence and principle. On the other hand, they offer reflection on a world that is accelerating in all areas. But in the end, the scale of the game trumps the engineering of the gears.

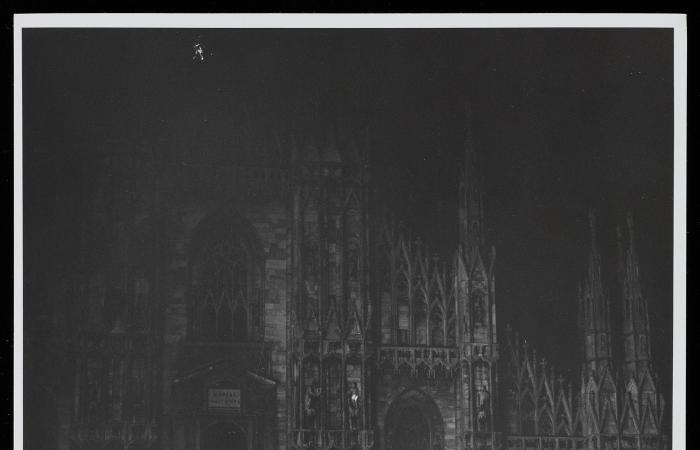

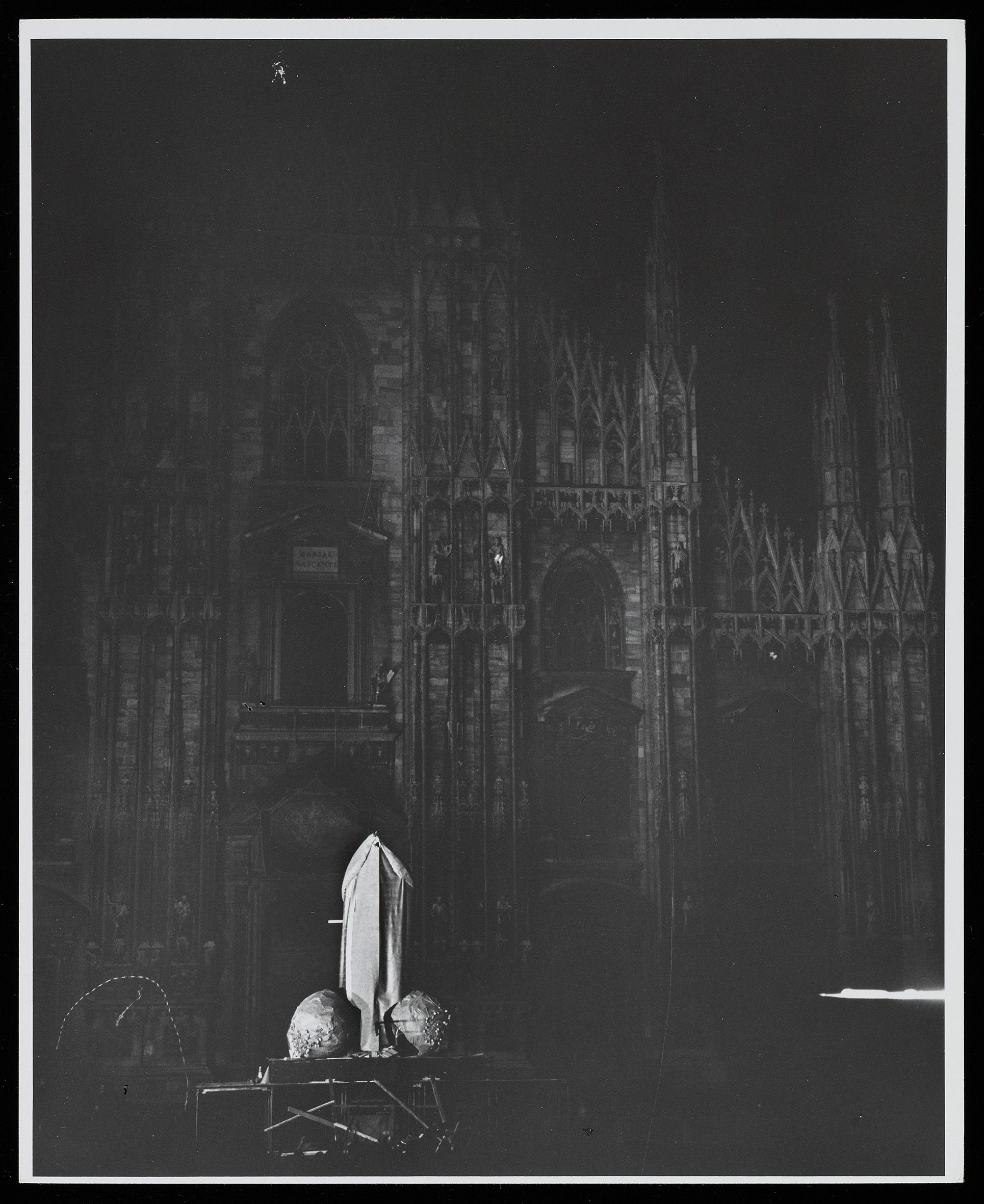

La Vittoria, performance/installation created on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of New Realism. Milan, November 28, 1970.

© SIAE, 2024 Photo János Kender and Harry Shunk

“The question of play is at the heart of his work,” explains the director of the Tinguely museum, Roland Wetzel. “He grew up in a Catholic family and Basel is Protestant. I think it gave him a different perspective on the world.”

The exhibition space is proportional to the intellectual grandeur and artistic immensity of Tinguely. Five thousand square meters are occupied by his sculptures. An adjoining room hosts a screening of the performance The Victorywhich originally took place in Milan in 1970: a huge penis ejaculating fireworks right next to the Duomo Cathedral, to celebrate the death of New Realism.

Visitors browse the exhibited works without chronology or continuity. These celebrate the slowness rather than the frenzy of today. Organic chaos reaches its peak with the deconstruction of a Formula 1 car (Pit Stop1984). Jean Tinguely reassembled the parts of the Renault RE 40 in a haphazard manner, and contrasted it with photos of the same racing car “flying” over the Monza circuit, and in the middle of a repair at the pit stop. Next to it, in a vertical spiral, is the sculpture Scary Carret – Viva Ferrari (1985), in honor of the Italian team.

“If you respect machines and get into their minds, you may be able to make a joyful machine, and by joyful I mean free,” Tinguely theorized.

“Pit-Stop”, 1984

Alto Piano Srl

Medical assistance

In other works, the audience actively participates by pressing a button with their feet to turn on the gear and bring the sculpture to life, as with the table Machine bar (1960-85). Meta-Matic no. 10 (1959), conversely, was out of service and had to be treated by the “doctor” of the works, Jean-Marc Gaillard, chief curator of the Tinguely museum collection.

“To heal, my instruments are simple: screwdrivers, pliers… You must connect your hands to your mind through your heart to love these works and listen to them. I’m usually there early in the morning, sitting or walking around the spaces and saying hello to the works. And I stay there, listening to them, in order to sense when something is not going as it should,” he says during his break, while he makes a small repair on the kinetic sculpture Rotozaza No 2 (1987).

The drawing machine par excellence: “Méta Matic n° 10”, 1959 (replica in the exhibition).

Alto Piano Srl

Jean-Marc Gaillard has a musical ear and lives among the cries and murmurs of these mechanical creatures. “Sometimes they catch a cold, like us. So I take them out of the exhibition,” he explains after having prescribed rest for Meta-Matic no. 10. When he is not restoring works by Tinguely, Jean-Marc Gaillard travels the world in search of similar elements and twin pieces.

“I only use old materials to replace a part. I always need something similar to the original. Animal skeletons, wooden wheels… My biggest problem is securing a stock for the next forty years,” concludes the “doctor”.

Tinguely’s life and work are intrinsically linked to his relationship with the artist Niki de St. Phalle. To learn more about the artist duo, click here:

Plus

Plus

The art of Niki de Saint Phalle cannot be limited to an exhibition at the museum

This content was published on

Dec 22 2022

The Kunsthaus Zurich celebrates the artist’s work. Although dense, the retrospective fails to fully convey its impact on the public.

read more The art of Niki de Saint Phalle cannot be limited to an exhibition at the museum

Text reread and verified by Virginie Mangin/ac, translated

from English by Françoise Tschanz/ptur