In an interview with the One TV channel, Saâda Arbane accused, on November 15, Kamel Daoud of having “dispossessed a victim of terrorism of his history, of his life, against his will ”, and this despite “the categorical refusals of his parents during their lifetime ».

History of trauma

Then aged 6, in 1993, Saâda Arbane was one of the victims of an attack by an armed group which she survived, but from which she still suffers numerous after-effects. Left with her throat slit by the attackers, Saâda Arbane can today only speak with help, due to the injuries inflicted on her vocal cords.

Having “took more than twenty-five years to forget [s]on trauma “, she believes that Kamel Daoud would have ” stirred up the wounds » of a story which she thought was “ the only one to decide how [elle devait en] to go out“. She also points out the responsibility of the wife of Kamel Daoud, psychiatrist, in the potential use of her story.

Medical follow-up very close to the novelist

Indeed, Saâda Arbane was accompanied by the psychiatrist, revealing details of her psychological intimacy during sessions. She claims to have been followed from 2015 until the Daoud family left for France, in several medical establishments in Oran, first for group therapy with her mother, then alone.

Kamel Daoud's wife would even have mentioned the writer's interest in the story of Saâda Arbane, and the latter would have clearly expressed her refusal to see her story changed into a book. In his testimony, Arbane says: “[S]his wife told me that he is writing a book, I told her: “Be careful, I don’t want it to be on me” . She told me: “No, it’s not about you at all.” . Several times during my consultations, I repeated to his wife: “Be careful, I refuse to let him do that.” »

Elements “purely fictional »

To support his accusations, Saâda Arbane evokes several points in common with Aube, main character of Houris: « My scar. My cannula. Conflicts with my mother. The operation I had to undergo in France, the pension I receive as a victim [du terrorisme islamiste]. Abortion, I wanted to have an abortion. The meaning of my tattoos [au niveau de la nuque et du pied]. The hair salon, I had a hair and beauty salon and it's in the book. Lotfi high school. The romanticized allusion to my passion for horse riding. »

In a press release sent this Monday, November 18, Gallimard editions, which publish Houris denounce “ violent defamatory campaigns » against the writer. “AndHourisis inspired by tragic events that occurred in Algeria during the civil war of the 1990s, its plot, its characters and its heroine are purely fictional», assures Antoine Gallimard, CEO of the house.

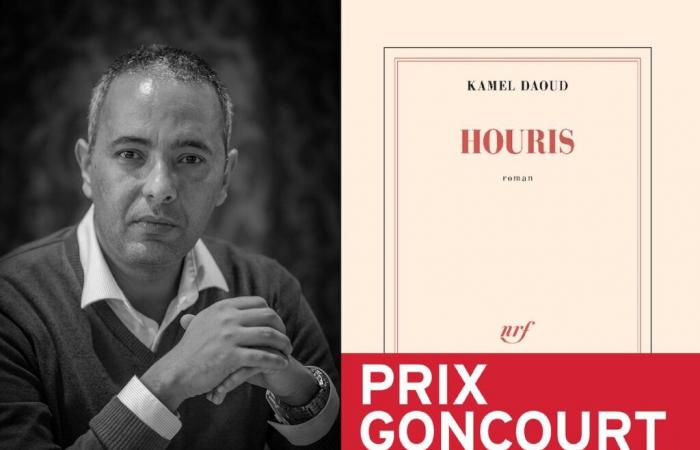

READ – Big favorite, Kamel Daoud wins the 2024 Goncourt

He further cites case law: “Since the lawsuit filed in 1896 over Jules Verne's novel,Facing the flagthe judges consider that any novelist is free to draw inspiration from real facts (historical, political, legal), real-life events and known people to create a work of fiction.»

In France, this freedom of artistic creation and dissemination may possibly come up against the right to respect for private life. Between literary inspiration and the revelation of intimate elements, the line is sometimes blurred, and controversies frequently arise, particularly in the field of autofiction. Among the latest to date, let us cite that aroundYogaby Emmanuel Carrère, a novel attacked by Hélène Devynck, his ex-partner, who mentioned a text published without his consent.

For Gallimard Editions, Kamel Daoud represents the prospect of a financially prosperous end to the year: after receiving the award, the author sold nearly 50,000 copies of his work, from November 4 to 10.Houristhus exceeded 120,000 titles sold.

A political target?

The editor again reminds that Kamel Daoud is not really well regarded by the Algerian authorities, and believes that the accusations are part of campaigns “orchestrated by certain media close to a regime whose nature is well known».

Re-elected last September with nearly 95% of the votes cast, outgoing President Abdelmadjid Tebboune, 79, has held this position since 2019. Voter participation was, however, at half mast, with only 5 million voters out of 24 million registered, while the space left for opposition remains minimal.

Shortly before this electoral deadline, the non-governmental organization Amnesty International denounced “a continued erosion of human rights through the authorities' dissolution of political parties, civil society organizations and independent media, as well as an increase in arbitrary arrests and prosecutions based on trumped-up accusations of terrorism”, in the words of Amjad Yamin, deputy regional director for the Middle East and North Africa.

France – Algeria, nothing simple

Diplomatic relations between Algeria and France have also deteriorated significantly since Emmanuel Macron approached King Mohammed VI in Morocco. At the heart of the discussions held last October, the future of Western Sahara, a territory located between Morocco and Mauritania. The first ensures that it is an integral part of its borders, while Algeria supports the independence of Western Sahara, demanded by the Polisario Front, a political and military movement.

The French president's support for the integration of part of Western Sahara into Morocco has upset Algeria, considerably cooling relations between the two countries.

In this context, the Goncourt Prize awarded to Kamel Daoud and the media exposure of the writer in France seem to fuel the animosity of the Algerian authorities. At the beginning of October, ActuaLitté revealed that the Gallimard editions found themselves “forbidden[e]s presence at the Algiers international book fair», organized from November 6 to 16. Daoud's novel seemed to be at the origin of this decision.

With this difference that the organizers of SILA, and the censors at the origin of this refusal, are less concerned with the content of the work than with the media coverage of the writer.

READ – How to guarantee creative freedom in the face of censorship?

Houriswill in fact not be broadcast in Algeria, where the evocation of the years of the “black decade”, between 1992 and 2002, is prohibited. The very violent clashes between the army and Islamist groups left between 60,000 and 150,000 dead, at least, without mentioning the missing, the injured and the traumatized.

History and its behind the scenes

At the beginning of the 2000s, the government tried to restore social peace with amnesty laws, preferring the expression “national tragedy” has “civil war“. In 2017, the mention of the period is even prohibited, to complete this facade reconciliation. However, it is also the time when the writer becomes a spearhead of the fight against Islamism, lending his voice to power to fight against the development of the ideology… to a certain extent.

In fact, the rise of Islamism in Algeria, as much as in other Arab countries, was, if not favored, at least observed without reluctance by the State. In the 1970s, the Red Peril was upon us and we then witnessed a rise in religious extremism, to break socialism, the left and more generally the emancipation movements which were gripping. So many proven historical elements that we do not find in the author's latest publication – certainly dubbed by the country's cultural elites.

Because in Algeria, Daoud as an editorialist, more than a writer ultimately, is quite annoying: displaying a certain social contempt, his media interventions, particularly in Le Point, make the readership cringe. Very critical of Algerian society, but also of religious practices associated with Islam, he is also perceived as a very French voice, a feeling reinforced by his acquisition of French nationality, in 2020, then his exile, a few years later .

Last August, Daoud explained that he was attacked in Algeria, “because I am neither communist, nor decolonial, nor anti-French», in an interview withPointwhere he is also a columnist.

The silent Goncourt Academy

Asked by ActuaLitté, Philippe Claudel, president of the Académie Goncourt, did not wish to comment. However, the question will perhaps arise: if the story arises from a violation of medical confidentiality – and there are documents attesting to this – will the jurors still support the awarding of the prestigious prize? This would be a first, certainly, but which would raise another question: could the members of the Academy have been aware of the way in which the story was written?

A few days before the awarding of the prize, Tahar Ben Jelloun, close to the writer, author Gallimard and Goncourt juror, had forcefully defended the work at the microphone of France Inter. And at the same time he refused to be involved in ensuring that the work was rewarded.

«If, indeed, Kamel Daoud has Goncourt, it would be an explosion. To the extent that everything that Algeria, finally the generals, wanted to hide for the civil war – because it is forbidden to talk about this civil war – will be known to the whole world and through translations throughout the world.»

What would he say today about Saâda Arbane's public declarations, incriminating the novelist? (see comments at 5'14)

Photography : Kamel Daoud, in 2015 (Claude Truong-Ngoc, CC BY SA 3.0)

By Antoine Oury

Contact : [email protected]