Every year, after Eid al-Adha, the Muslim festival of sacrifice, Morocco witnesses another vibrant festivity. This carnival or parade, often observed between Eid and the Islamic New Year (Hijri New Year) as well as Ashura (the tenth day of Muharram, the first Islamic month), sees participants dressed in goatskins and masks parading through the streets.

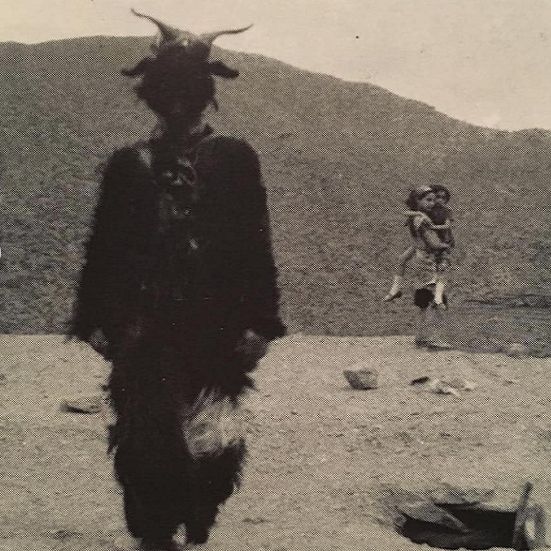

Known as Boujloud (Arabic) or Bilmawen (Amazigh), meaning “one who wears skins, leather or furs”, this tradition sees young Moroccans parade and dance each year in costumes painstakingly made from skins. , horns and even limbs of animals sacrificed during Eid. Photos and videos of these elaborate costumes, reminiscent of Halloween with their colorful wigs, scary contact lenses and 3D makeup, are flooding social media.

However, Boujloud has many detractors. Pan-Arabists who consider it a pagan practice “foreign” to Moroccan culture, while Islamists associate it with “Satanism”, denouncing its timing after a major Islamic holiday.

A deeply rooted tradition

Boujloud, however, is deeply rooted in Moroccan history, reflecting the practices, beliefs and social interactions of his ancestors. Moroccan anthropologist Abdellah Hammoudi notes that this tradition has existed in Morocco for centuries, with first documentation in the late 19th century.

Hammoudi, in his book “The Victim and Masks: An Essay on Sacrifice and Masquerade in the Maghreb”, emphasizes that during this period, Boujloud captured the attention of foreign observers, particularly the French. On the other hand, he points out that Arabs rarely recognized festivals outside the official Islamic calendar.

Therefore, the first descriptions of Boujloud come mainly from “foreigners”, Hammoudi maintains. He indicates that these masquerades were practiced throughout Morocco, from the Atlas Mountains, through the north among the Jbala and Rif tribes, as well as in large imperial cities such as Marrakech and Fez. Accounts from foreign researchers and ethnographers document variations in this tradition across different regions and tribes.

Interestingly, Boujloud even reached the royal court, becoming a frequent component of Ashura celebrations. As Hammoudi notes, the French anthropologist Edmond Doutté documented in 1907 the appearance of Boujloud “in the early morning streets of Marrakech, some time after the sacrifice.”

According to French diplomat Eugène Aubin (quoted by Hammoudi), Boujloud continued throughout the period following Eid in Marrakech, accompanied by open-air performances during Ashura. Aubin describes Boujloud in Marrakech as “Herrema Bou Jlud”, a tradition known for its comic performances, especially in front of the sultan.

“This custom is very developed, real comic plays are performed there,” wrote Aubin, emphasizing in particular their presence “in front of the sultan.” It detailed performances featuring a Qadi (judge) and a “burlesque trial”. The culmination being the “mockery” of the European ambassador, his interpreters and, above all, the ministers.

Although the ministers were uncomfortable at being ridiculed, they were expected to “put on a brave face”, while the sultan and their colleagues laughed out loud. A similar spectacle called ‘fraja’ (‘the great entertainment’) was also performed before the sultan. In Fez, a similar show called “fraja” was also presented before the sultan during Ashura. Abdellah Hammoudi cites Edmond Doutté’s account of this spectacle in 1907, not only at the sultan’s court but also at that of the rogui Bou Hmara, opposed to the reigning dynasty.

The integration of Boujloud into the royal festivities underlines its deep roots in Moroccan culture, appreciated by the sultan himself.

Merger and evolution

Beyond royal court circles, anthropologists view Boujloud as an example of how Moroccans merge ancient traditions with Muslim festivities. Hammoudi explains that the choice of moment, between the sacrifice and the New Year, marks an important temporal transition. He notes that many observers interpret these festivals as “ancient pagan ceremonies for the renewal of nature” integrated into the Muslim calendar.

Although the symbols and elements may suggest a connection to past traditions, Hammoudi says this blend of religious and cultural practices is prevalent across diverse cultures. However, he criticizes the approach of the French North African school which insists on “survivals”, implying a clear distinction between pagan and Muslim festivals.

This approach, even recognizing historical links, tends to minimize the symbolism of Muslim festivals by comparing them to supposedly pagan origins. It neglects not only the individual significance of each festival, but also the deeper meaning that emerges from their coexistence within rituals, Hammoudi asserts.

Symbolic interpretations

Other ethnographers offer various interpretations of Bilmawen. Hammoudi mentions Laoust’s hypothesis, comparing Boujloud to the Roman god Lupercus, protector of farmers and crops against wild animals. Laoust suggests that Bilmawen plays the role of a scapegoat, absorbing evil spirits through the ritual of touching the participants. Another interpretation sees Boujloud as the incarnation of an aging god, sacrificed and resurrected into a vigorous animal.

Hammoudi connects this symbolism to the sacrifice during Eid al-Adha, suggesting that the Islamic holiday may have adopted an ancient Berber festival that also began with a sacrifice. He puts forward the idea that the new festival could be considered a continuation of the previous one, possibly disguised by Christian and then Islamic traditions.

Apart from its symbolic interpretations, Boujloud also serves as a platform to challenge social norms. Masquerades temporarily reverse the rules of daily life. Hammoudi suggests that they represent a “secondary foundation for the roles of civilization”, where Bilmawen embodies the necessary chaos that completes the social order. He argues that these masquerades highlight generational hierarchies, with young people confronting the traditions of elders through initiation rituals and forms of social protest. Themes of sexuality, procreation and power dynamics are explored through Boujloud’s playful performances.

Despite the criticism, Boujloud remains a vibrant tradition in Morocco. It is a complex celebration that mixes elements of history, religion and social commentary. Bilmawen’s colorful costumes, lively performances and playful chaos continue to capture the imagination of Moroccans of all generations. Whether seen as a continuation of ancient traditions, a platform to criticize society, or simply a joyful celebration, Boujloud endures as a testament to Morocco’s rich cultural heritage.