A life of notes

From her adolescence until her suicide in 1941, at the age of 59, Virginia Woolf frantically recorded her readings, research and thoughts on loose sheets or notebooks. Seven thousand pages were digitized and then put online on woolfnotes.com, a site hosted by the prestigious King’s College London. Until then, to find their way through this labyrinth of papers, academics had as their only breadcrumb trail an index, published in 1983 by the American researcher Brenda Silver: a simple census, accompanied by their summary, of texts that were sometimes barely readable. , scattered between London, the Sussex archives (where the writer’s final resting place is located) and the New York Public Library. ” In 2016, I realized that we had the technology to link this index to the entirety of each of the notebooks”, traces the English researcher Michèle Barrett, initiator of the project. Eight years later, this sum, finally ordered, is freely accessible.

Read also | Virginia Woolf: a life of writing

Add to your selections

Fragile remains

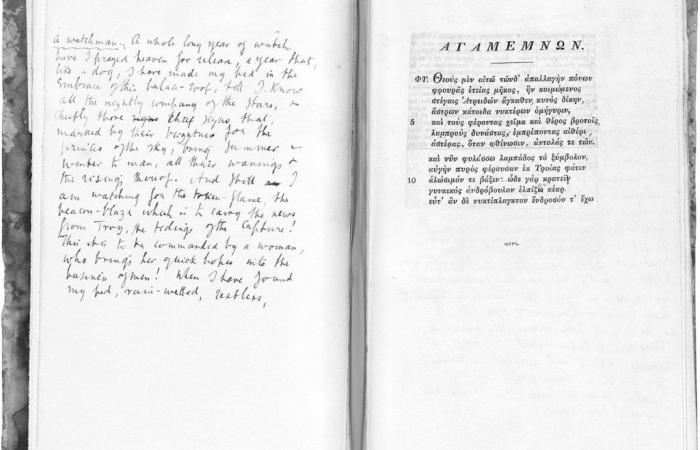

On the “Visual Index” page of the site, we discover notebooks of various sizes, with heterogeneous boxes. Michèle Barrett details: “Many of them feature cover material from the Hogarth Press [la maison d’édition fondée en 1917 par Virginia et son mari, Leonard] or were hand-bound by the writer. Some of the most interesting have also reacted to the environment in which they were kept for a long time. » Traces of humidity, stains, torn spines… Signs of the vagaries of life and sometimes hazardous storage – Michèle Barrett once found in Leonard Woolf “three large piles of cards never photocopied or cataloged in a box”. Now fragile notes are forever: King’s College has committed to keeping the site online “in perpetuity”. “Sometimes I almost come to regret the quality of our images, says Michèle Barrett. In the future, researchers will find it even more difficult to justify absolutely having access to the originals. »

Reading sheets

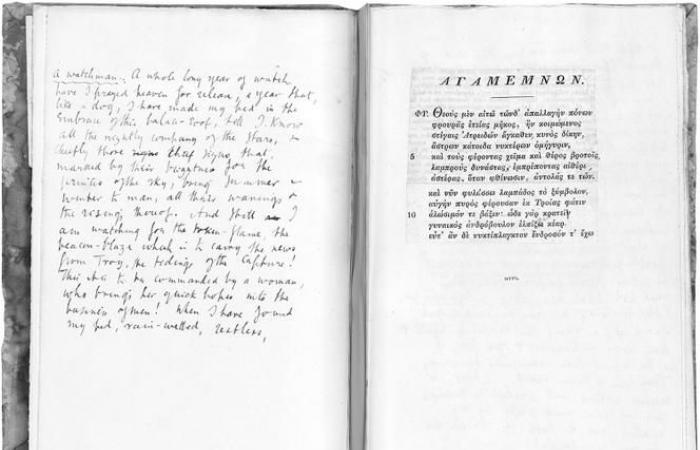

“Like most uneducated English women, I like to read – I like to read books bought in bulk”, wrote Virginia Woolf in her essay A room of one’s own. In reality, the author was not without education: the initiative made it possible to unearth, in the archives of King’s College, documents proving that she studied Greek, Latin, German and history. Anna Snaith, co-lead researcher on the project, explains: “This training then allowed her to develop very rich literary analyses, which she shared in her notebooks. » One of them is entirely devoted to Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe others mention Stendhal, Freud or Montaigne. Yet another, called “Agamemnon’s Notebook”, is “an extraordinary object, Michèle Barrett is moved, which juxtaposes the Greek text with a translation that she copied and annotated”. A very personal edition made by his own care.

You have 23.27% of this article left to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.