To curb the global obesity epidemic, two measures would be effective: regulating advertisements for “junk food” aimed at children, as was done recently in the United Kingdom, and including the Nutri-Score in advertisements.

The UK authorities recently announced that from October 2025, advertisements for foods high in sugar, fat and salt will be banned on the internet and on daytime television (they will only be allowed from 9 p.m.). Why such a measure regarding candies, biscuits and other chips and sugary drinks?

Regulating junk food advertising: a public health issue

The stated objective is to protect the youngest from these advertisements. Indeed, numerous scientific research indicates that advertising for this type of food contributes to the increase in overweight and obesity among children and adolescents. According to the British government, such regulations will prevent 20,000 cases of childhood obesity per year.

The stakes are high since it is now scientifically well established that overweight and obesity promote the appearance of cancers, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, depression and other chronic pathologies. Each year, these conditions are responsible for 2.8 million deaths worldwide, 1.2 million in Europe and 180,000 in France, where half of the population is overweight or obese.

However, these figures are increasing at an impressive rate, leading the World Health Organization to say that combating the epidemic of overweight and obesity constitutes one of the most important public health challenges of the 21st century. .

Furthermore, on an economic level, overweight and obesity are increasingly costly to society: the cost is currently nearly 30 billion euros per year for France, and it continues to grow.

A receptive young audience

Advertising for food and drink products influences the food consumption of children and adolescents. Several scientific works have already demonstrated this. We know in particular that younger people prefer the brands they see in advertisements.

However, in France, more than half of the food advertisements seen by children on television concern foods and drinks of poor nutritional quality, very often manufactured by large agri-food groups.

To increasingly influence consumer choices, brands use digital means of communication to which children and adolescents are particularly exposed. Televisions, but also smartphones and computers are full of advertisements distilled into videos, films, series broadcast on the Internet and on the most used social networks, and even in video games.

icosha/Shutterstock

They use the language and communication codes of children and adolescents, conveying their persuasive messages in seductive forms, particularly via the speeches of influencers, true stars of the Web.

This bludgeoning influences the youngest without them always being aware of it. For example, it has been shown that exposure to a very simple advertising message, on which a brand of sweet drink appeared, was sufficient to increase children’s affective evaluation and purchasing intention, measured one week later, whereas the latter had no memory of having ever seen her before.

The multiple strategies of brands

To appear despite digital applications intended to block advertisements on browsers and mobiles, brands are seeking to erase the boundary between clearly identified advertising and their presence in the “normal” landscape on the Internet. For example on a sports or fashion site, an advertisement can be formatted to resemble an article written by a journalist. In a news feed on social networks, an advertisement can slip into the middle of the posts and stories published by our contacts. As we often read quickly, we can wrongly equate it with a message posted by another Internet user.

This type of advertising, called “native advertising”, also makes it possible to inhibit the critical reactions that receivers might have towards commercial messages. Thus, once brands have entered young people’s memories, they are more likely to buy them.

Marketers in the food industry also use evaluative conditioning techniques: for example, they look for images, music, etc., which trigger positive emotions in young people.

In the media and on the Internet, they then associate them with the brand, even if there is no logical connection between the two. All that remains is to repeat their presentation together so that the child’s brain, often without their knowledge, associates the two: the brand is then automatically more appreciated, because it is linked in memory to positive emotions .

It is also common for the brand to be associated with celebrities (a singer, a famous athlete), cartoon characters or amusing mascots (a tiger, a lion, etc.), particularly on packets of cereals for children’s breakfasts. children.

For children, resisting advertising is very difficult

All these advertising effects are powerful. However, children and adolescents are vulnerable groups who do not have the intellectual maturity to take into account the possible deleterious effects, in the medium and long term, of their immediate eating behaviors.

Even media education where we explain to children the pitfalls of advertisements and how to protect themselves from them would not succeed in reducing their desire to obtain the advertised products.

The regulations implemented in the United Kingdom are therefore perfectly justified to preserve the health of children and adolescents. In France, the situation is currently different: for decades, our country has opted for a system where we “trust” agri-food industries and media companies to make ethically and socially responsible decisions. The idea is that they would be able to limit themselves, aware of the deleterious effects that their advertisements can have on public health.

However, studies show that this self-limitation does not really take place. A large number of works have shown the ineffectiveness of such a system for public health. Many agri-food industries design messages using techniques of seduction, or even manipulation, to promote their products rich in sugar, fat and salt, which they also broadcast massively on television at times when a large number of children are watching. .

Various learned societies, public health authorities (Public Health France, High Council for Public Health), consumer associations (Foodwatch, UFC que Choisir, Consumption Housing Living Environment, etc.) or other non-governmental organizations (such as Communication and Democracy ) have long been asking the French public authorities to put in place regulations similar to those in the United Kingdom, for example by prohibiting the broadcast of advertisements for Nutri-Score D and E foods during the day on television and on the Internet.

However, for the moment, their request has remained a dead letter.

The Nutri-Score in advertisements, a second effective technique

Given the importance of public health issues, we wanted to test the effectiveness of a second approach, complementary to the previous one: the inclusion of the Nutri-Score in advertisements.

Safety System/Shutterstock

As a reminder, the Nutri-Score, now well known to the population, is a five-level nutritional labeling system, ranging from A to E and from green to red, which makes it easy to recognize differences in overall nutritional quality between foods. .

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of this approach, we set up a large-scale randomized controlled trial (a research methodology guaranteeing a high level of scientific proof), involving 27,085 participants from the NutriNet-Santé cohort, distributed by drawing lots into three groups.

Participants in the first group were exposed to advertisements for foods with contrasting nutritional qualities, in which the Nutri-Score was displayed. The affected products belonged to nine different food categories: cereals, drinks, breakfast, bars, biscuits, savory snacks, cold meats, ready meals and desserts.

The second group was exposed to the same advertisements, but without displaying the Nutri-Score. The third group was a control group: its members were not exposed to the advertisements.

All participants were asked to answer an Internet questionnaire regarding their perceptions of all products and their intentions to purchase them, consume them and give them to children.

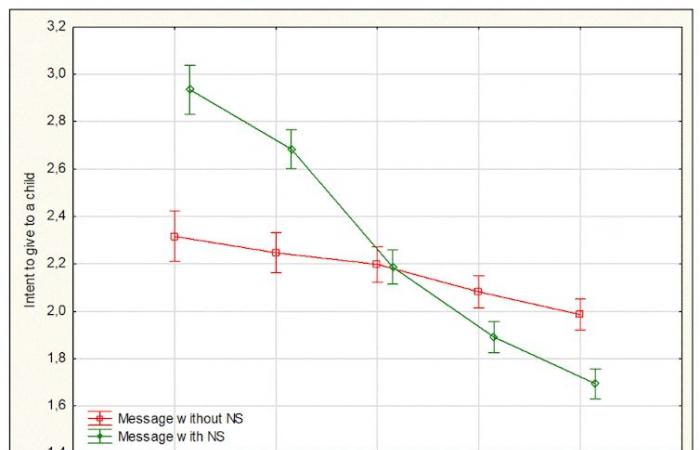

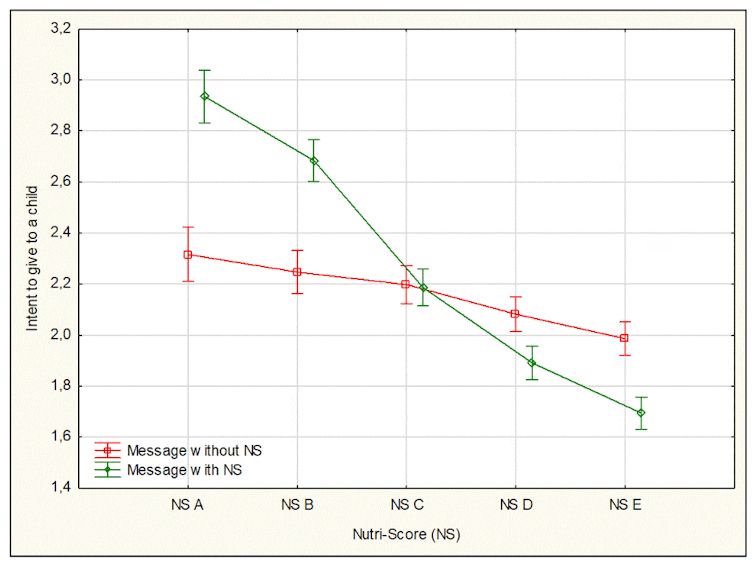

The results show that when the Nutri-Score is displayed in advertising messages (compared to no display of the Nutri-Score):

• perceptions of foods were better for those classified Nutri-Score A or B (of the most favorable nutritional quality) with stronger intentions to buy them, consume them and give them to children;

• perceptions were, on the contrary, less good for foods with Nutri-Score D or E (of more unfavorable nutritional quality). Intentions to buy them, consume them and give them to children were weaker;

• there was no or little effect on perceptions and intentions to purchase and consume foods of intermediate nutritional quality (Nutri-Score C).

Didier Courbet, Author provided (no reuse)

Displaying the Nutri-Score in advertising messages would therefore help consumers direct their choices towards foods of better nutritional quality, more favorable to health. Regulations making it mandatory to display this nutritional logo in all food advertisements could therefore constitute an effective public health measure.

Linking this measure with a measure limiting daytime advertising for foods of poorer nutritional quality on the Internet and in media such as television would make it possible to improve the fight against the epidemic of obesity and chronic diseases linked to nutrition among adults and children.

It now remains to find the political will to implement such measures. A challenge, as certain manufacturers in the agri-food sector have shown significant lobbying for several years to prevent the adoption at European level of the Nutri-Score, despite its widely scientifically demonstrated effectiveness.