The episode is well-known, but no matter, it is with each reminder a little more picturesque and emblematic of the twists and turns that the History of art likes to play.

Inspired by Turner’s seascapes discovered during a trip to London in 1871, Claude Monet painted a canvas in Le Havre in the fall of 1872 that he named Print, rising sun, and not, as would have been better, Landscape at rising sunor Vue du port du Havre. The work was exhibited at the Société Anonyme of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers in the spring of 1874, in the former studio of the photographer Nadar, Boulevard des Capucines. The critic of Charivari se gausse: “What does this painting represent? Impression ! Impression, I was sure of it. I also said to myself since I’m impressed, there must be some impression in there. » He didn’t think he was saying that well. The word, supposed killer, was out. Returning like a boomerang to the face of academia, he was going to make his fortune.

It was exactly one hundred and fifty years ago. Six institutions in France today are dedicated to the Impressionists: Orsay, Marmottan, the Orangerie Museum, the Le Havre Museum, the Pont-Aven Museum, the Museum of Impressionisms in Giverny, right at Monet, the Jerusalem of impressionism, with Auvers-sur-Oise where Van Gogh was martyred, as Golgotha.

The Giverny museum, created in 2009, does not yet have any real funds. It is, for the moment, a welcoming museum which is lent works based on the magical name of Giverny, works which in return it “givernises” by affixing its own label. Required, prestige obliges, to be present in this 150e anniversary of Impressionism, the museum has launched the race for loans, while dozens of international institutions compete for masterpieces for this same anniversary. Despite the competition from these mega-museum machines, Giverny won its bet, choosing an almost new theme: impressionism and the sea.

Of the eighty works exhibited, including twenty-eight Boudin and nine Maufra, eleven belong to Giverny, sixteen are on loan from the Musée d’Orsay, eleven others come from a private collection, through the Galerie de la Presidency, in Paris. The rest comes from various provincial or foreign museums. The external harvest was good.

Walking through the picture rails, we experience a pleasant feeling of deja vu, we are as if invited to attend a family reunion between artists, all friends, finding themselves in Giverny at the “boss” a century later, and arguing about a past of which they have all together become the eponymous heroes, recognized and celebrated everywhere. By rubbing shoulders with each other, by finding themselves in cross-exhibitions, they ended up constituting a sort of impressionist union where the same cards, the same works and the same names are eternally reshuffled, in new distributions, according to new grids. But the themes themselves eventually wear out. It’s a bit of a limit for the genre. Will the success of Impressionism, which has not been denied for a hundred years, crossing, indifferent to the century, cubism, surrealism, abstraction, free figuration, whatever else, experience its purgatory?

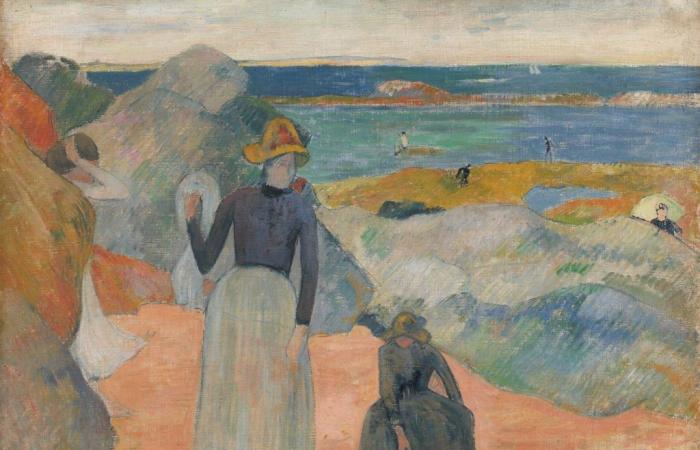

Few surprises this spring at Giverny, except a masterful Monet, from America, entitled Low tide at Petites-Dallesa captivating Tahitian Gauguin, Te Vaa Landscapefrom Le Havre, and a very handsome Jongkind, The Port of Antwerp, from Rennes. A big absentee, however, Seurat, but in the impossible, no exhibition curator is required. Likewise, the Japanese artist Henri Rivière is conspicuous by his absence. For the rest of the score, which sometimes draws the line, Eugène Boudin takes the lion’s share.

Except for the sublime and terrifying A grain, coming from the Morlaix museum, Boudin puts an end to “the sea of drama and melodrama” (Edmond Duranty), these seascapes which, until him, only dealt with waves, breaking waves and foam, storms, of shipwrecks, threatening skies and sailors in distress. The first, he made the foreshore and the beaches places for painting, sketching live sea workers, vacationers, socialites, ladies in crinolines, elegant boaters, intrepid bathers, sailors. Their slim silhouettes with their minute details are marvels of rendering; one seems to hear the dandies with canes and hats coming down from the Hôtel des Roches Noires on the beach of Trouville murmuring their compliments to the white hothouse ladies all enveloped in the wind in their canvas cabins with multicolored stripes, or taking refuge in the shade of ‘an umbrella ; we think of Guardi’s gondolier scenes at the decline of the Serenissima, tiny snapshots full of life and movement.

Boudin wanted to “run after boats and follow the clouds, paintbrush in hand”.

Baudelaire, who met him in Honfleur in 1859, was not mistaken. After Constantin Guys and his lorettes, the poet in turn proclaimed Eugène Boudin the painter of modern life. Giverny owes him a lot.

Impressionism and the sea

The exhibition is open every day (including public holidays), from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. (last admission 5:30 p.m.), from March 29 to June 30, 2024.

Museum of Impressionism Giverny

99 rue Claude Monet

27620 Giverny

+33 (0)2 32 51 94 65