(Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic) Nadège Jean-Baptiste migrated to the Dominican Republic three years ago in the hope of starting a new life far from the tribulations of Port-au-Prince. His project turned into a nightmare.

Published at 5:00 a.m.

“It is not good for Haitians to live here. People treat us like animals,” she says, stroking her sleeping boy’s head.

The 3-year-old child and his mother have come a long way. In October, the 33-year-old undocumented woman was apprehended in the capital, Santo Domingo, and immediately taken to a detention center.

PHOTO MARC THIBODEAU, THE PRESS

Nadège Jean-Baptiste, a Haitian woman who was expelled from Santo Domingo without her 3-year-old child

“They grabbed my arm violently. It hurt me very, very, very badly,” said the Haitian national, who was placed in a stinking cell where she had to sleep on the floor.

Worried to death at the idea of being separated from her son, she managed to alert the neighbor who was looking after him for the day.

He tried to return the child to his mother, in vain. Mme Jean-Baptiste found herself the next day in a truck with dozens of other migrants being sent back.

The neighbor even followed the vehicle with a motorcycle to try one last time to return the boy.

“He ended up having a completely white face from the dust. I cried, cried, cried,” notes Mme John the Baptist.

As soon as she was dropped off on the Haitian side at the Elías Piña border post, 250 kilometers west of the capital, she contacted smugglers to return to the Dominican Republic.

PHOTO MARC THIBODEAU, THE PRESS

Haitians who came to make purchases in the Dominican Republic pass through the Elías Piña border crossing to return to Haiti.

She went from motorcyclist to motorcyclist to avoid traffic stops after agreeing to pay 15,000 pesos, or $375.

Haitians in Santo Domingo chipped in to help her and she repaid them on her return, 48 hours after her deportation, calling on friends living in the United States and Canada.

Today, Mr.me Jean-Baptiste no longer dares to leave the room she rents for fear of being evicted again.

“I live like a parasite, I live at the expense of others,” she says, crying.

The experience is in no way unique. The Dominican government announced in September its decision to step up the return of undocumented Haitian migrants, promising to return up to 10,000 people per week.

The most recent tally shows that nearly 240,000 Haitians have been returned in 2024, including around 100,000 in the last three months of the year.

Dominican President Luis Abinader said the country must act to stem migration from Haiti, which is amplified by insecurity linked to powerful gangs.

He clarified that the international community could not blame the country for its action – which he assures is legal – while nothing is being done to truly restore order on the Haitian side.

PHOTO MARC THIBODEAU, THE PRESS

Soldiers take Haitian migrants off trucks who will be expelled at the Elías Piña border post.

Since the president’s announcement, screened vehicles from the “migratory control” service have been going almost every day to the main border crossings in the west of the country to send back Haitians apprehended all over the Dominican territory.

During his passage at the Elías Piña border post in early January, The Press witnessed the arrival of eight trucks full of Haitian nationals.

Hundreds of resigned-looking migrants got out of the vehicles under the watchful gaze of soldiers before passing through a gate leading them without further formality to the Haitian side.

PHOTO MARC THIBODEAU, THE PRESS

Cristina, a Haitian national who has just been deported to Haiti, gives a thumbs up in greeting.

A 38-year-old woman, Cristina, had time to explain, before being drawn into the movement, that she had lived for 20 years in the Dominican Republic and did not know what awaited her in Haiti.

My whole family is on the Dominican side.

Cristina, Haitian national expelled from the Dominican Republic

A teenager, with tears in his eyes, explained that he had lived in the Dominican Republic for five years before falling silent.

The operation took place under the watchful eye of the country’s director general of immigration, Lee Ballester, a high-ranking soldier who arrived a little earlier by helicopter.

“We control, we control,” said the government representative during an impromptu interview.

Unable to quantify the number of Haitians to be sent back, the soldier limited himself to saying that it would be necessary to continue until the level was “sustainable” for his country. The most recent official estimate, in 2017, suggested the presence of 500,000 Haitians in the country. Some organizations today speak more of 1 million.

Vice Admiral Lee Ballester, who called to order soldiers threatening to seize devices used by The Press to film the disembarkation of migrants, asked whether the subject received a lot of attention in Canada, where many tourists come from each year.

-

A “deep humiliation”

Across the country, soldiers and police are tracking Haitians, often making arrests based on the color of their skin.

“They come day and night,” says Waizon Pierre, a 25-year-old migrant encountered about fifty kilometers from the border town of Dajabón. He had just narrowly escaped arrest by hiding in a field.

PHOTO MARC THIBODEAU, THE PRESS

Waizon Pierre, a Haitian migrant who narrowly escaped arrest in the west of the country

Even people with valid papers are likely to be expelled if they do not carry them with them at the time of the check, notes Rigard Orbé, who works for a Haitian NGO helping expelled people.

He explains that the experience is experienced as “a profound humiliation”. Especially since some targeted people have lived in the Dominican Republic for years, even decades, or were actually born there and know nothing about the country where they are sent.

The Dominican government, in addition to raising security issues, argues that Haitian migration weighs heavily on the country’s institutions.

Many children of undocumented Haitian nationals attend schools. Health facilities care for many migrants regardless of their status.

PHOTO MARC THIBODEAU, THE PRESS

Le maire de Dajabón, Santiago Riveron

The mayor of Dajabón, Santiago Riveron, complains that the uncontrolled arrival of migrants poses many problems.

He cites in particular the fact that the municipal cemetery is squatted at night and is annoyed that Haitians “throw their waste in the street every day” without any other consideration.

The Dominicans are generous, but the country “cannot carry two burdens at the same time”, namely its population and that of the neighboring country, he said.

The rhetoric of the authorities echoes that which is often heard particularly in the United States, where many politicians are alarmed by the supposed security impact of the influx of undocumented migrants and their impact on public services offered to citizens. in order.

An essential workforce

The Dominican government must come to terms with the fact that Haitian labor is essential to its economy.

A report from the Dominican College of Economists last year said 700,000 Haitians work in agriculture, construction and other sectors using low-skilled workers. Its authors warned that the economy could not absorb more migrants from the country.

In the United States, which has a population 30 times larger than the Dominican Republic, the estimated number of undocumented workers was 8.3 million in 2022, according to the Pew Research Center.

Mr. Orbé believes that the intensification of expulsions in his country reflects an “opportunistic” decision by President Abinader, who used the issue of immigration to consolidate his political support by playing on the nationalist fiber of the Dominicans.

The government’s hard line on expulsions contrasts with the fact that the border remains porous in many places.

Nowhere is the paradox more apparent than in Elías Piña, where a twice-weekly cross-border market allows thousands of Haitians to temporarily enter the Dominican Republic for the day to sell goods or vegetables and make purchases. They are expected to return in good faith at the end of the day.

-

PHOTO MARC THIBODEAU, THE PRESS

A truck loaded with products purchased on the Dominican side during a cross-border market day returns to Haiti.

-

PHOTO MARC THIBODEAU, THE PRESS

The cross-border market attracts thousands of Haitians who come there to obtain products, often essential, or to sell their goods.

1/2

Trucks overloaded with goods of all kinds passed from the Dominican Republic to Haiti during the passage of The Press. Individuals came home on foot with a live chicken in hand, an ironing board, washing tubs or even a shelf.

Soldiers on site carried out occasional checks of papers without apparent logic.

Francisco Cueto, a career academic based in a rural community near Dajabón where many undocumented Haitians reside, believes that the authorities are trying to “maintain their legitimacy” among the Dominican population by increasing expulsions.

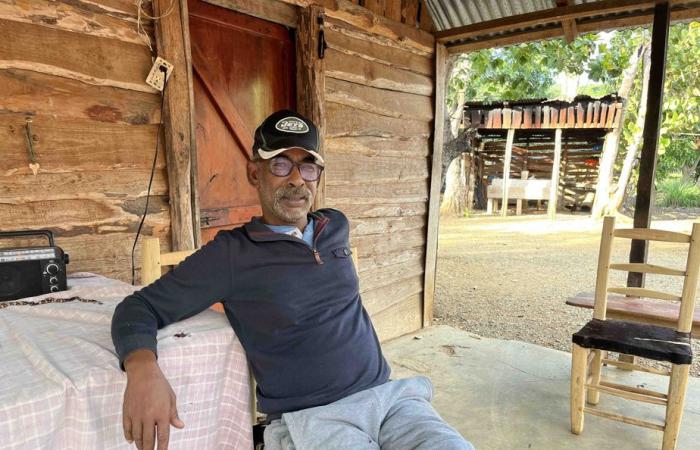

PHOTO MARC THIBODEAU, THE PRESS

Francisco Cueto, who lives near Dajabón

Anti-Haitian sentiment is very strong and has often been used by the political elite in the country’s history.

Francisco Cueto, a career college student who lives near Dajabón

Part of the government nevertheless seems to have understood the need to find a solution to promote “organized and humane immigration”, believes Mr. Cueto.

William Charpentier Blanco, who heads a migrant rights organization based in Santo Domingo, notes that the pursuit carried out by the authorities promotes a form of “dehumanization” of Haitians which will taint the entire Dominican society for a long time.

He recently heard a group of children who were “playing” not far from his home, capturing undocumented Haitian migrants by separating their roles.

The Dominican Republic in brief

- Population : 10 815 857

- Official language : Spanish

- Religion : Evangelical (50%), Catholic (30%), none (18.5%)

- GNP per capita : 8856 $ US

- Unemployment : 5% at the end of 2023, average of 10% from 2000 to 2024

Ethnic groups

- Mixed: 70.4%

- Noir : 15,8 %

- Blanc : 13,5 %