Was the death whistle really used to frighten the sacrificial victims of the Aztecs?

For the authors of the study, researchers in neuroscience at the University of Zurich (Switzerland), their discipline is able to provide an answer to an archaeo-ethnological question on the function of an instrument designed by an indigenous people having lived in what is now Mexico between the 13th and 16th centuries.

We know that the Mexica made and played various musical instruments: mainly percussion, but also trumpets, and wind instruments, flutes or whistles. For the latter, we do not really know their context of use, even if several hypotheses have been put forward to explain their form and function.

The whistle represents the god of the Underworld

There are several variations of whistles, but those used for this study published in the journal Communications Psychology are skull-shaped whistles (skull whistles, death whistles). Specific to the Aztecs, they are made in the image of the god Mictlantecuhtli, a divinity reigning over the underworld.

But the sound that escapes from it also suggests a clear association with the wind god, Ehecatl. Moreover, these two deities are complementary, their iconographic association can be interpreted as the representation of the dualism between life and death.

Finally, according to Swiss researchers, the nature of the sounds made from this instrument could also suggest that it was used in combat, which was accompanied by sonorous music. But this hypothesis is refuted by Arnd Adje Both, who specifies that “there is no ethnohistorical, iconographic or archaeological evidence of the use of these instruments in warfare.”.

Statuette representing the god Mictlantecuhtli exhibited at the British Museum in London. Credits: Simon Burchell / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / Wikimedia Commons

A sacrificial victim held a whistle in each hand

As for the contexts in which whistles were discovered, they are not significant enough to deduce their true use. According to Arnd Adje Both, “only one archaeological context tells us that it was played on the occasion of human sacrifices.. Two specimens were in fact excavated in a burial dedicated to the temple of Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl within the walls of Tlatelolco, a city-state whose remains were found under the soil of Mexico. The sacrificial victim held a whistle in each hand.

“It seems that both instruments were played on this occasioncontinues the archaeomusicologist. It is very likely that priests played these instruments on special and ritual occasions. A 16th century ethnohistorical account also relates that Aztec merchants, who were part of the 'upper class', played these whistles in front of a sacrificial victim before the sacrifice. The whistle is called chichtliaccording to the sound it emits, onomatopoeically transcribed as 'chich'. It's not 100% certain that it's the skull whistle, but it's possible.”

Read alsoHuman sacrifices to feed the gods

A construction capable of generating the Venturi effect

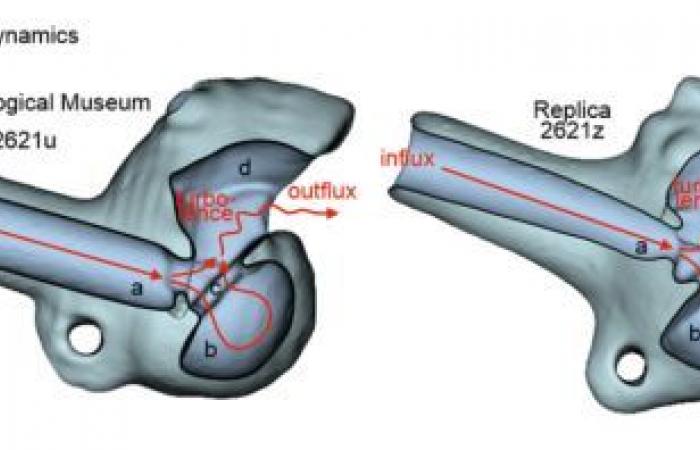

Aztec whistles in ethnological museum collections are made of clay and similarly constructed, as computed tomography (CT) scans have revealed. They have four parts:a tubular air duct with a narrow passage, a hemispherical back pressure chamber, a collision chamber and a bell-shaped cavity”explain the Swiss researchers.

This architecture thus suggests that “the acoustic motor mechanism is based on the Venturi effect which generates a constant process of suction, collision and turbulence of the air”they add. Consequence: “When playing intensity and air velocity are high, acoustic distortions and a harsh, piercing sound character result.”

Cross-section reconstructed by computer-assisted tomography (CT) of a whistle preserved at the Ethnological Museum in Berlin. Credits: Sascha Frühholz et al., 2024

Comparative acoustic tests

To find out the function of the whistle, the researchers decided to test on humans the effect produced by isolated sounds from this instrument. Several protocols are put in place, intended to qualify these sounds whose pressure is modulated in order to obtain variants.

At the end of this comparative study carried out on European listeners whose average age was 25 years, it appears that the whistle would produce a sound “hoarse” et “piercing”. “Other similar sounds are unspoken human voices and tool or technical sounds with a raspy, shrill sound quality (alarm clocks, chainsaw, emergency horn).”develop the researchers.

An unpleasant sound

Which leads them to conclude that the sounds emitted by Aztec whistles could induce “reactions of alert, surprise and affectivity in human listeners”and that their nature, considered more artificial than biological, corresponds to “psychoacoustic and affective profile typical of aversive, frightening and surprising sounds“far from relaxing music, pleasant to the ear.

Another specimen of Aztec whistle preserved in the Ethnological Museum in Berlin. Credits: Claudia Obrocki / Sascha Frühholz et al., 2024

MRIs are enough to justify the use of the whistle during sacrifices

This rather negative reception, however, says nothing about the function of the object. This is why the researchers are carrying out two additional neuroimaging experiments.

Their goal: to observe which areas of the brain are activated when listening to the sounds produced by whistles, in order to examine “whether this decoding occurs at the level of basic auditory processing or rather at the level of higher order cognition”.

To the extent that it is these regions of the brain (lateral, medial frontal cortex and insula) that are activated, the researchers deduce that the sounds produced “have a symbolic and associative meaning”.

Which, in their eyes, constitutes solid evidence to support the hypothesis of the use of whistles in the ritual context – sacrificial in particular – and to deduce their function. “The skull-shaped whistles may have been used to frighten victims of sacrifices or those present during the ceremony.they go so far as to conjecture.

Do we hear like the Aztecs?

This is quite an interpretative leap! Supported, what is more, by the evacuation of a major problem: is it really possible to deduce the effect produced on the Mexican population from the reception of a person living in the 21st century? Yes, the researchers justify themselves: “we believe that certain basic neurocognitive mechanisms are common to modern humans and humans from Aztec cultures. Many cognitive, affective and auditory mechanisms are shared between humans and the closest ape species.”

Decontextualization rhymes with overinterpretation

But what about the cultural context? And then are we able to say how the Mexica experienced different kinds of sounds? Our modern Western society has agreed on what is harmonious or discordant, but are these categories universal?

No, of course, replies Arnd Adje Both, who specifies that if the shape of the whistles is conventional, “there is more headroom in terms of sound. Some instruments 'scream' when blown hard, but are more 'raucous' when played softly; others have generally softer, less 'aggressive' sounds. The 'screaming' or 'scary' sound characteristics are our Western impression, the Aztec perception may be different – my personal interpretation being that they all howl like the wind, from the Aztec point of view.”

Read alsoSacrifices, cannibalism and revenge: archeology reveals a bloody episode of the conquest of Mexico by the conquistadors

When neuroimaging hides ethnocentrism

However, the study is based on strictly scientific data, such as neuroimaging; but deplores the archaeomusicologist. “Unfortunately, the anthropological point of view is sorely lacking here. The physical effect on the brain could be identical between ancient Aztecs and modern individuals, of course, but that does not mean that the perception of sound is therefore identical. This poses a problem at the level of the results, which are partly Eurocentric.”

The song of the God of the Underworld

As for considering the terrifying role of the whistle in sacrificial death, for Arnd Adje Both it is clearly “of an overinterpretation, which neglects what we know about Aztec culture. The victims of the sacrifices were often honored as representatives of the gods and, in all cases, heavily drugged with psychoactive substances. So I don't think these instruments were made to frighten the victim of the sacrifice.”

For his part, he is considering several possibilities, “but we can't be sure of any of themhe tempers, because the sources are weak. For example, it is possible that these instruments were used to call the victim to the underworld. As they represent Mictlantecuhtli, their sound could also be linked to his voice (or his 'song', according to the Aztec conception).”

The Aztec fantasy

Suffice it to say that the biased conclusion of this study is hardly convincing. The association of the terms “skull”, “death”, “chilling”, “scary”, “scream”, immediately announced the color. It corresponds to a “vision of Aztec culture conceived as terrifying and bloodthirsty” which led to interpreting in a way “whimsical”from replicas that have nothing to do with the original instruments, the sounds emitted by the “whistle of death”, confirms the archaeomusicologist.

But just as we only hear what we want to hear, we only arrive – even when following the strictest scientific protocol – at the conclusion towards which we wish to move. No surprise, therefore: at the end of this study, we know nothing more about the Aztec whistle.

You can listen to some sounds emitted from original whistles and replicas prepared for this study on the dedicated page named “The scary sound of Aztec skull whistles“.