On the night of December 2 to 3, 1984, his little cries were muffled by the screams of residents who were desperately trying to escape the methyl isocyanate fumes.

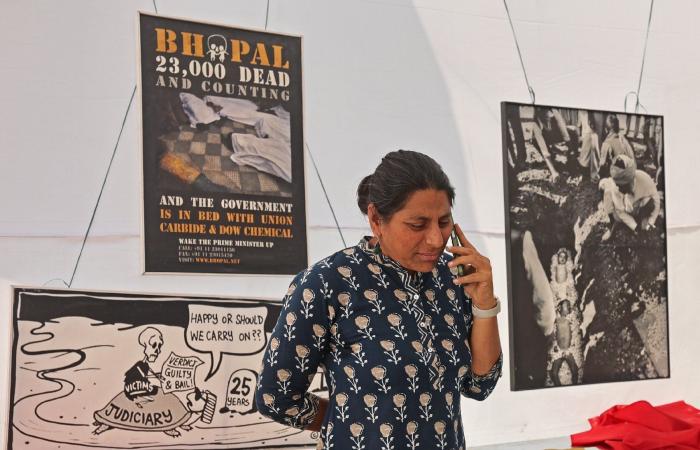

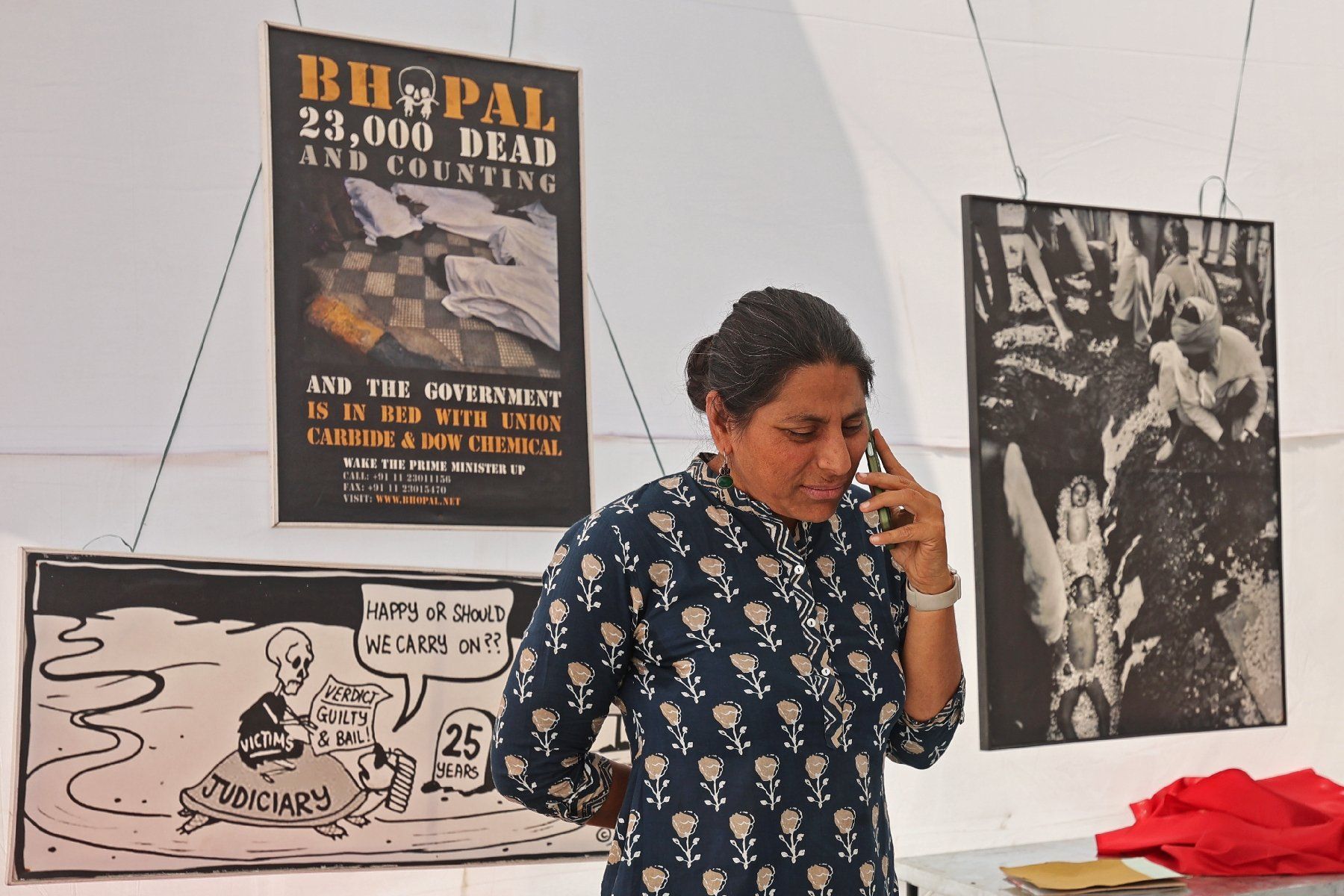

One of the world's worst industrial disasters left around 3,500 dead in the first three days. Some 25,000 people died in the years that followed.

Four decades later, this disaster still poisons the lives of Ms. Devi and those born with deformities.

Ms. Devi, a daily wage worker, suffers from constant pain. One of her lungs is not fully developed and she is constantly sick.

“My life is hell,” laments this small and frail forty-year-old, wiping her face in a slum in Bhopal, the capital of the state of Madhya Pradesh (center).

“My parents called me Gaz. I think that name is a curse. I would have liked to die that night,” she told AFP, with tears in her eyes.

Thousands of residents, most living in a huge shantytown located between the city and the factory, were trapped in their sleep by the fumes of the deadly gas escaping from the factory of the American group Union Carbide.

– “No sign of respite” –

Nathuram Soni, 81, was one of the first to witness apocalyptic scenes.

“People were foaming at the mouth. Some had defecated, others were choking on their own vomit,” says Mr. Soni, looking towards the now abandoned factory.

With a handkerchief over his nose to protect himself, he carried his wailing neighbors, many of them small children, by cart to the hospital.

Rashida Bee, co-founder of the NGO Chingari Trust, which provides free care to descendants of families hit by the disaster, believes that those who died were lucky.

“At least their suffering has ended,” she sighs. “The unfortunate ones are those who survived.”

This year, more than 150 children with cerebral palsy, hearing problems, speech problems and other disabilities were admitted to his facility.

She attributes these pathologies to the gas leak and the contamination of the water table caused by the dumping of toxic waste.

Analyzes of groundwater near the site revealed the presence of chemical substances – carcinogenic and responsible for birth defects – 50 times higher than the thresholds tolerated by the American Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

“This tragedy shows no sign of letting up,” notes Rashida, 68, several of whose family members have died of cancer since the disaster.

“The soil and water are contaminated, which is why children are still born with malformations.”

– Higher mortality –

According to NGOs, Union Carbide, bought in 2001 by the American conglomerate Dow Chemical, dumped chemical waste into the environment for years before the disaster.

Asked by AFP, Dow Chemical did not comment.

Tasleem Bano, 48, is convinced of the link between the factory and congenital diseases.

Her son Mohammed Salman was born with malformations, “his twin brother died in my womb,” she explains.

“Mohammed survived, but he couldn't say a word until he was 6 years old,” she explains, showing the orthopedic device that allows her son to stand up.

“The doctors say he is in this state because of the gas,” says Tasleem, who lived near the factory the night of the tragedy.

Asked his name, the 12-year-old boy responds with a simple smile.

Like him, hundreds of children in the Chingari center have difficulty speaking, walking or eating.

At the Sambhavna Trust clinic, survivors regularly queue for treatment.

“The data shows very clearly that the exposed population has a much higher mortality rate among the exposed population than the rest of the population,” says Satinath Sarangi, founder of Sambhavna.

“In 2011 (…) we found that there was 28% more mortality among people exposed to the gas.”

– Responsible companies –

Mr. Sarangi, 70, says the fumes of the deadly gas affected the immune systems of affected populations and led to chromosomal aberrations.

“Children of parents exposed to gas have many more birth defects.”

Union Carbide agreed in 1989 to pay $470 million (444 million euros) to the victims. But the latter were not consulted and each only pocketed $500.

The current owner, Dow Chemical, has refused to pay further compensation.

The main accused, the former president of Union Carbide Warren Anderson, died in 2014 in the United States without having been convicted.

Rachna Dhingra, an activist with the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, believes the survivors have not received justice.

“The residents of the martyred city continue to fight (…) to hold these companies accountable across the planet,” says the activist, regretting that “Bhopal has taught companies how to get away with it” .