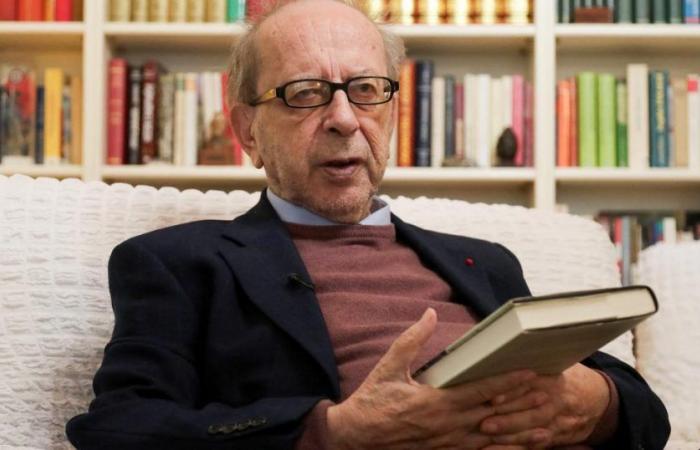

A political refugee in France in 1990, the novelist left behind a work with a powerful epic breath, mixing sharp political analysis with yesterday’s legends. He died of a heart attack in Tirana hospital on Monday morning.

“If you trust literature, literature alone, it will be your heavenly protection. Nothing can happen to you”. Until 1990, the year he requested political asylum in France, Ismaïl Kadaré managed to make this motto his own, happily using the metaphor in his numerous books, which were very critical of totalitarian regimes, while his own country Albania was under the rule of a dictator.

Ismail Kadare died Monday morning at the age of 88 from a heart attack, the Tirana hospital said. He arrived there “without signs of life”, doctors gave him cardiac massage, but he “died around 06:40” (8:40 local time), the hospital said. The writer embodied for a long time the paradox of being a writer who was both recognized and persecuted. If his books were published in Albania, they were often immediately banned by the regime or at best mutilated. He was nevertheless happy about this fact, arguing that these works were all the more valuable for his compatriots who rushed to get hold of them.

Winner of several prestigious prizes including the Man Booker International Prize (2005) and the Prince of Asturias Prize (2009), the author was also regularly considered to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. In France, since 1996, he had been an associate member of the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, promoted to Commander of the Legion of Honor in 2015. He was in fact the best-known Albanian writer in the world, having contributed letters to to talk about this small country stifled for almost half a century by the dictator Enver Hodja.

Ismaïl Kadaré was born in 1936 in Gjirokaster, the pearl of southern Albania which was also the birthplace of the dictator a few years earlier. His father was a postman and the young boy showed an early interest in Greek tragedians and Shakespeare in particular. As a child then a teenager, he experienced all the avatars of communism, first in the Russian fashion, then Chinese and finally Albanian when his country successively became angry with the two great tutelary powers. At seventeen, the student at the University of Tirana was noted for his verses. He was sent to the Gorky Institute in Moscow, a breeding ground for authors and critics. He enjoyed it as a student but later declared that he was unhappy as a writer. In fact, his first collection of poems was published by a Russian publisher, his texts untouched but accompanied by a preface which denounced the harmful influence of the West. The young Kadaré accepts this publication. There, this duality takes root which marks him for many years. He is harshly criticized but tolerated by a regime which sees in him a foil to be sent from time to time to the West. For a long time, he put up with this state until the day he could no longer bear compromise and remained in Paris with his wife and two daughters.

In the meantime, in 1960, the young student returned home to Albania. If you can, through literature, not take the diet seriously, you are saved.” he declared to the New Observer in 2005. In fact from the start, he endeavored to undermine that of Albania. After Drinking Daysthe story of two little thugs indifferent to the socialist cause, a work immediately considered decadent, he published in 1963 what is considered his first novel. The General of the Dead Army is a great success in his country. It follows the unsuccessful attempts of an Italian officer who came to Albania to recover the bodies of soldiers who had died a few years earlier. Instead of his compatriots, who could not be found, he brought back the remains of German soldiers! The West discovers through this book, translated seven years after its publication in Albania, that the small, muzzled country in the Balkans is home to a real writer with things to say.

Under the communist tyranny of Enver Hoxha

The novelist will subsequently continue to decipher the human and metaphysical dimension in novels on the fringes of the tale, in the process stripping away the paranoid delusions of a few. In The Palace of Dreams (1982), he depicts a country subject to dictatorship whose inhabitants must obligatorily summarize their dreams which are immediately meticulously listed. In La Pyramide (1992), he tells the story of the misfortunes of a pharaoh who tries to rebel against ancestral traditions by refusing to have a grandiose tomb built for himself. He will eventually give in and the construction will drag on as crises and revolts occur. At the same time, he runs the literary review, Albanian Letters, published simultaneously in Albanian and French, this language being the only one officially taught by his country. He becomes a member of the establishment.

Unilaterally appointed deputy of the People’s Assembly, he benefits from certain advantages compared to the rest of the population, a private car, the right to receive part of his rights from his translations abroad, an apartment rather large. He continues to publish books at a steady pace but the shell of the writer who takes refuge in literature is gradually cracking. In 1982, he suffered a smear campaign. Ultimate irony: the dictator takes his side. The break came in 1990, five years after the death of Enver Hodja. Ramiz Alia, the man who succeeded him, did not meet the hopes of Kadaré who believed he saw in him the man of change and reforms. While he promotes Palace of Dreams In France, the writer decides to ask for political asylum. He writes “in such a duel between a tyrant and a poet, it is always, as we know, the poet who wins, even if, for a time, he may seem defeated”.

When the regime finally fell, he returned to the land of eagles, returning several times a year even though his home remained in Paris. In France, he continued to publish with the same regularity, faithful to Fayard, the publishing house of his original publisher Claude Durand (1938-2015). It was also in France that he undertook the herculean task of revising his entire work, pruning or completing works that he had self-censored. When the dictatorship fell, his new novels became lighter and shorter. Micro-novels replaced the sagas, but criticism was no longer necessarily hidden in symbolic form and Albania was still at the heart of his writings. At the end of the 1990s, he became involved in the cause of the Albanians in Kosovo. Virulently opposed to Serbia, he gave numerous interviews and public speeches.

Calm will then return, lulled by the regularity of the publications. After The Doll in 2015 in which he evokes the figure of his mother, he published in 2017 what is perhaps his most intimate story. Mornings at Café Rostand, named after his Parisian headquarters, is presented as a collection of composite texts written during the previous decade lived between France and Albania, with which he had eventually made peace. His latest novel, published in 2022, Disputes at the topemblematic of his entire work, reconstructs the telephone conversation between Stalin and Pasternak during the arrest of the poet Mandelstam in the 1930s.

In 2020, the Bouquin collection (Robert Laffont) cleverly reissued two of his works, Twilight of the Steppe Gods and the diptychThe Time of Quarrels devoted in part to the dissensions between little Albania and its powerful communist neighbors, China and the USSR, at the time of the Cold War. The French then discovered the original version of the text, which was blacked out by the Albanian regime when it was released in 1973. It remains the best depiction of daily life in a dictatorship by the man who described himself as “a normal writer in a crazy country ».