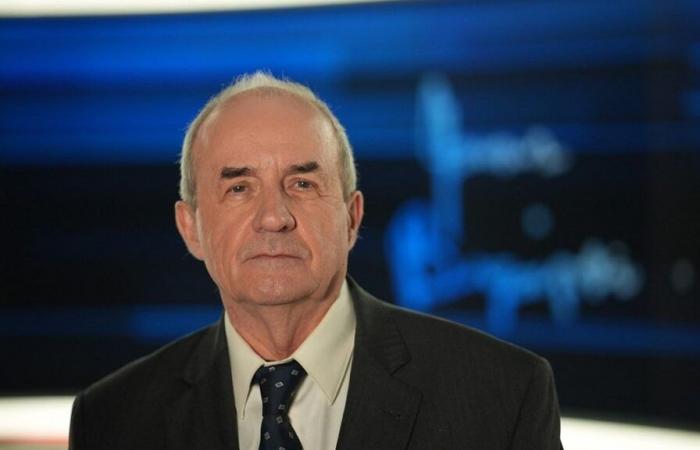

Euronews spoke with Janusz Bugajski, Senior Fellow at the Jamestown Foundation in Washington, to understand the situation and prospects of Central Asia in the context of Russia’s war against Ukraine, the influence of China and the post-American election.

ADVERTISEMENT

Euronews: Central Asia, rich in oil, gas, strategic minerals and at the crossroads of Eurasia, is an area of geopolitical interest for Russia, China and the West. How could US elections change or increase US influence in the region?

Janusz Bugajski: First of all, American and Western diplomatic vocabulary does not recognize the expression “zone of geopolitical interest” or at least feels uncomfortable with it. Then-Russian President Dmitry Medvedev spoke about Russia’s zone of state interests after the 2008 Russo-Georgian War.

Under the Biden administration, U.S. aid to Central Asia declined significantly as the United States withdrew its troops from Afghanistan and aid was redirected to Ukraine. President-elect Donald D. Trump recognizes the importance of the region’s natural resources and wants to contain China and possibly Russia. It is in the strategic interests of the United States and the EU to develop closer ties with the region, including in investment, trade, transport links and security cooperation.

Euronews: What has been the main dynamic in relations between Russia and Central Asia since 1991? Have the relationships always been conflictual or cooperative, and what has defined them?

J. B. : Relations between the former Soviet republics during the early years of Yeltsin’s presidency were relatively cordial. Russia focused on its domestic problems. Central Asian countries seized the opportunity to strengthen their independence. Kazakhstan’s first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, played a key role in this nation-building process as leader of the region’s largest state in terms of territory and GDP, with the longest border with Russia.

Unlike the three Baltic states, the Central Asian states have not experienced a recent period of state formation. They had to undergo three simultaneous transformations: political, economic and international. These include the creation of independent political institutions free from Moscow’s centralized control, economic reforms aimed at establishing market economies and dismantling the failed communist model of central planning, and participation in international relations as independent states no longer dependent on the decisions of the Kremlin. Kazakhstan played a leading role in all three processes.

Euronews: What are the legal and diplomatic mechanisms that link Russia to Central Asia? Can this be attributed only to the sphere of post-Soviet colonial and cultural heritage, or is it something else?

J. B. : After centuries of expansion, the Tsarist Empire conquered all of Central Asia at the end of the 19th century. The legacy of this repressive colonial policy persists today, as a new generation of Kazakhs, Uzbeks and other peoples rediscover their national identity and history. The role of national leaders such as Nazarbayev and Karimov in this national renaissance is still insufficiently recognized. Contrary to Moscow’s expectations, no Central Asian state openly supported Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the war itself deepened Kazakhstan’s reassessment of, for example, the Soviet era as imperial oppression.

At the same time, Central Asian leaders are well aware that Russia remains one of the dominant powers in Eurasia and is supported by China, the other great power. A large part of their trade is still with Moscow. They cannot alienate Russia through hostile actions. On the contrary, they must pursue a policy of balance between Russia, China and the West in order to preserve their freedom of maneuver. Kazakhstan has been at the forefront of this movement for decades to protect the young state and ensure its economic development.

Euronews: But today the balance is “unbalanced” because of the war in Ukraine. How is Russia trying to maintain its influence over the Central Asian states?

J. B. : The war against Ukraine has significantly weakened Russia in terms of military capabilities and financial resources. At the same time, Moscow can use political, informational and financial tools to try to replace Central Asian governments considered too independent or pro-Western, such as Georgia or Moldova. The most effective way for Central Asian states to defend themselves against such a scenario is three-pronged.

First, the multi-vector foreign policy led by Nazarbayev since the independence of Kazakhstan guarantees greater influence on the international scene. Secondly, increased regional integration will reduce economic dependence on Russia or China. Third, closer economic and trade ties with Europe and the United States will enable the transatlantic community to take a greater interest in the security and independence of Central Asia. Ties with the Pacific region, including Japan and Korea, are also important.

Central Asian countries cannot boast of having a NATO nuclear umbrella to protect their security. On the other hand, they can better protect their national interests thanks to a multi-vector policy. This involves avoiding close cooperation with a single state and engaging with numerous international organizations, including the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Organization for Cooperation and Security in Europe (OSCE), the Organization of Turkic States (OTS) and the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA).

It should be noted that Kazakhstan has just announced its refusal to join BRICS.

In these formats, constructive initiatives aimed at strengthening Central Asia by resolving border issues and creating a united front against terrorism, promoting cultural cooperation and environmental protection can be implemented. Kazakhstan has also invested in the Nurly Zhol infrastructure development program (in English).

Euronews: Kazakhstan is trying to present itself as a new diplomatic center, a “Switzerland of the steppes”, and its attempts to mediate in the Syrian conflict are particularly remarkable. Can Central Asia play a role in ending the war in Ukraine? And can she do it to her advantage?

J. B. : Just as Austria, Finland and Switzerland played a role in reducing tensions during the Cold War, today’s global antagonists could meet on neutral ground in Kazakhstan, as they did in Vienna , Helsinki, Geneva and Lausanne in the last century. Central Asian states would not be able to negotiate an end to the war in Ukraine, but they could provide neutral ground to discuss and resolve war-related issues, such as prisoner exchange, protection of civil infrastructure or guaranteeing grain exports across the Black Sea. Coordination on nuclear safety and environmental protection in different parts of the world is also important, and Kazakhstan in particular is keen to provide a platform for international cooperation.

Euronews: What do you advise Central Asian countries to avoid becoming Russia’s next victim? Does China have a role to play?

J. B. : To strengthen their independence and avoid being drawn into competing blocs in a polarized world, Central Asian states must both strive to strengthen regional integration and internationalize. This will strengthen their economic power, their investment potential, their security and their international reputation. A more consolidated and unified region will be better able to protect itself from negative foreign influences.

After the collapse of the USSR, attempts at regional integration were made, but they had only limited effect. In 1994, President Nazarbayev initiated an agreement to create a Central Asian Union with Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, initially focusing on economic cooperation. This project was canceled due to continuing rivalries between some states, disputes over scarce water resources, competition for external investment, and increasing attempts by Beijing and Moscow to dominate the region through strategic of division and conquest.

Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union and China’s Silk Road Economic Belt programs were launched to undermine Central Asia’s autonomous and independent regional initiatives. In 2007, Nazarbayev put forward the idea of a Central Asian economic union with free movement of goods, services, capital and people. The objective of this union would be to strengthen regional security, economic growth and political stability.

Despite the obstacles, the integration project has been relaunched in recent years, notably thanks to a marked improvement in relations between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the two largest states. Besides deepening economic ties, the two governments have sought to address pressing regional issues, ranging from environmental concerns and mass migration to cross-border drug trafficking and threats from Afghanistan and ISIL. Integration has also been promoted by the B5+1 initiative led by the United States.

Euronews: In the past as in the present, personalities like Karimov or Nazarbayev have become a symbol of post-Soviet regional stability. A number of new political figures are more oriented towards reform. What is their strategy?

J. B. : Nazarbayev had to lead three transformations simultaneously: the transition from the Soviet planned economy to the market economy, the building of the state and the development of links with international partners. Today, for example, Uzbekistan, under the presidency of Shavkat Mirziyoyev, is also reforming its economy and establishing diversified economic and diplomatic relations.

So the Nazarbayev model is being adopted by other countries because it works. Regional integration must be developed so that the whole is greater than its parts, and to a large extent this is already the case. EU countries want Central Asia to have a common market of 82 million consumers.

This would strengthen the sovereignty of each state, increase intra-regional trade and investment, and give the region a clearer identity on the global stage. When the war in Ukraine reaches its climax, Central Asian states will face a major challenge: either strengthen regional integration and global political and economic interaction, or become peripheral actors, increasingly intertwined in the Expanding Russian or Chinese imperial carpet.

Janusz Bugajski is a senior fellow at the Jamestown Foundation in Washington, DC, and the author of two new books, Pivotal Poland : Europe’s Rising Power etFailed State : A Guide to Russia’s Rupture.*