November 13, 2024 will mark the tenth anniversary of the death of Alexandre Grothendieck, distinguished mathematician and great thinker of radical ecology. He spent a large part of his life between Lozère, Hérault, Ariège, where he died.

“It was one of the strongest psychological shocks of his life.” 1966, Bures-sur-Yvette, in Essonne. Alexandre Grothendieck learns the most beautiful news that a mathematician can hope for. He is expected in Moscow to receive the Fields Medal. He refuses. Going to the USSR is inconceivable for a former inmate of Nazi camps. Worse, receiving money for your mathematics is an affront: “The recognition, the honors, the facilities… It always made him uncomfortable,” his daughter, Johanna, would later tell.

He sent his medal to the government of Vietnam, as a form of support. This is what his science should be used for. Politics. The fight for human rights.

A scholar apart

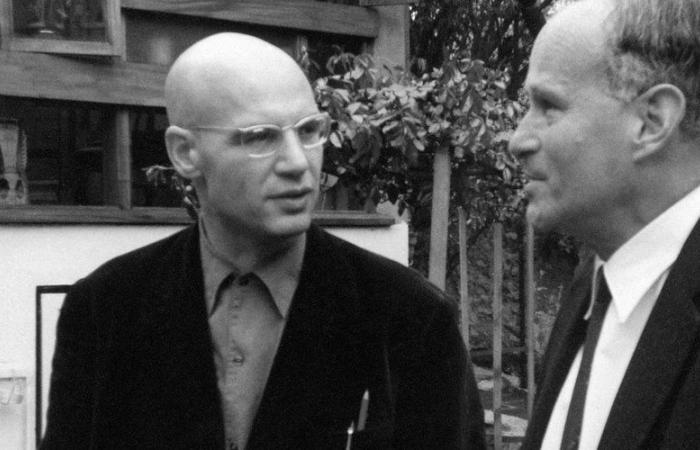

He was never like the others. Always more creative in his demonstrations, more visionary, more free. From the 1960s, he taught at Ihes (Institute of Advanced Scientific Studies), which was created for him. “I met Grothendieck in 1964”, remembers Luc Illusie, who was one of his students. “I went to see him in his office and explained my math problem to him. And then he said to me: 'No, that's not how you should see things.'”

With Grothendieck, we had to go further. Luc Illusie describes his master as a man who praised exchange with his students, who always pushed for rigor and self-sacrifice. “I felt like I was having an adventure. What he was doing was so new, so impressive.”

A life tormented by war

Grothendieck has never known long, quiet rivers. Born in Berlin in 1928, he waited for years for his parents who left to fight for the Popular Front in Spain. When he reunited with his mother and father in 1939, the whole family fell prey to the Nazis. His father, a Jew of Russian origin, was transported to Auschwitz, where he was murdered. His mother, a journalist by profession, will be interned with her son in Lozère, at the Rieucros camp.

Despite this, young Alexandre manages to go to class along the small country roads. When the war ended he graduated. He remained in Occitanie and enrolled at the math faculty of Montpellier. At the start of his thesis, he began to get noticed. His teacher sent him to Paris to study with the mathematicians Charles and Dieudonné.

The genius

It was from there that the student prodigy began to build his legend. The two mathematicians entrust him with fourteen problems to solve. He has to choose one to work on for the next few years. Grothendieck retrieves the list, and begins working on one of the problems. Then, two, then three. In a few months, he manages to resolve everything.

He drags his shirts, his jeans, his work jackets and his round glasses to the desks of the biggest universities in the world. Scientists praise the prowess of this researcher who always carries baskets of fruit in his suitcases. A slightly eccentric man, who teaches on the lawn, who brings croissants to the students, who invites them to dinner at his house. “Grothendieck was extremely helpful, remembers Luc Illusie. He invited me to dinner at his house, with his wife and five children. His wife, Mireille Dufour, was quite charming. When you are a mathematician at this level, you don’t have much time for your family, but I remember him as a good father.”

Too visionary

A life of a scientist, and soon an activist. During major congresses, he did not fail to demand the release of political prisoners in the USSR, to denounce the Vietnam War, or to criticize industrialization and the dangers of nuclear waste.

“At Harvard, he said: 'You are crazy for continuing to do math. We must stop scientific research… There are more urgent tasks ahead of us.'underlines his student. “What saddened me was that by rejecting science, he isolated himself from the group he was a part of. It was not the mathematicians who rejected it. It was he who rejected them.”

In 1970, he learned that Ihes was partly financed by the Ministry of Defense and resigned. He leaves to teach in Montpellier. In the 80s, he created the movement Survive and live, first consortium of activist scientists for ecology and antimilitarism.

He is on trial for having hosted Kuniomi Musanaga, a Japanese Buddhist monk, in his house north of Hérault. He decides to be his own lawyer and declares: “I plead guilty to the offense of hospitality.” The court dismisses the case, which he refuses. He appeals and asks to be sentenced. He will get his six months suspended sentence.

He moved to Ariège, to Lasserre. His contemporaries began to describe him as a mad scientist, a hermit, full of hallucinations. Soon, they say “this French Einstein” that he “lives like a minimum wage earner”. He wrote tens of thousands of pages, today estimated at several million euros. At the end of the 1990s, Grothendieck invited Jean Malgoire, his most brilliant student, who would also receive the Fields medal. “He told me, take what you want, I’ll burn the rest.” The student does so, next to a 200 liter can of gasoline.

To prevent his knowledge from being misused, he preferred to make everything disappear. Today, all that remains of the scholar are pages scattered in French archives, including in Montpellier, and the memory of a man too brilliant for his world. Prometheus transformed into Cassandra: “I have no doubt that before the end of the century, major upheavals will change the way we see science,” he predicted.