Once upon a time, it would have seemed unthinkable for the president-elect of the United States to threaten “economic force” to demolish the “artificially drawn” border with Canada and turn his northern neighbour into the 51st state of the Union.

Yet as outlandish as Donald Trump’s latest pronouncements might sound, is he really such an aberration? After all, the United States and Canada were hardly born in a spirit of mutual affection. Both owe their origins to the American Revolution. Indeed, one of the foundational moments in Canada’s history was the arrival of tens of thousands of loyalist refugees after the tax-dodging debacle of the 1770s and 1780s.

In the decades that followed, the American republic’s leaders made no secret of their ambitions to push the border further north. When war broke out in 1812 they launched multiple invasions of Upper Canada, now the province of Ontario. Fortunately, however, the British colonial troops — aided by local militias and their native allies — held firm, earning themselves a hallowed place in Canada’s national mythology.

President-elect Donald Trump referred to Justin Trudeau as the “governor” of the “great state of Canada” after their meeting to discuss punitive US tariffs

SPENCER PLATT/GETTY IMAGES

• Trump mocks Justin Trudeau with new nickname amid tariff tensions

That was not quite the end of the affair, though. Even during the reign of Queen Victoria some Americans dreamt of driving the British out of North America and though their final attempt was a shambolic failure, it deserves to be better known.

The story began in December 1837 when a group of political reformers, frustrated by the conservatism of Upper Canada’s ruling elites, launched an abortive uprising from Montgomery’s Tavern, an inn just outside Toronto.

The Battle of Montgomery’s Tavern, near Toronto in December 1837, led to the end of an uprising by political reformers

Alas, far from being a second American Revolution, the would-be revolt fizzled out within days. The local militia easily held off the rebels, the tavern was burnt to the ground and the surviving reformers bolted south across the American border. For a few weeks, their leader, a Scottish-born journalist called William Lyon Mackenzie, tried to establish a breakaway Republic of Canada on an island off Niagara Falls, devising his own currency and a flag based on the French tricolour.

But this too ended in disaster. As British troops bombarded the island, Mackenzie fled to New York, where he was eventually imprisoned for violating the Neutrality Act. The threat to Upper Canada, however, had not quite gone away, since hundreds of Mackenzie’s supporters were still hiding in the wooded hills of border states such as Vermont, New York and Michigan. Their American neighbours gave them a warm welcome: with anti-British feeling running high, many donated food, money and guns to the rebel cause and held rallies and meetings in support.

By the spring of 1838, tens of thousands of Americans had signed up to so-called Hunters’ Lodges, modelled partly on the secret societies organised by French-speaking exiles in Vermont. Dedicated to the cause of Canadian revolution, these had four degrees — Snowshoe, Beaver, Grand Hunter and Patriot Hunter — and required the blood-curdling oaths beloved of all secret societies of the day.

-To us, the Hunters’ Lodges sound like a joke. But to the authorities they were a genuine problem. That summer they attacked steamboats in the Great Lakes, seized uninhabited Canadian islands, ambushed British border patrols, burnt taverns across the border and even seized and torched a steamer called the Sir Robert Peel. All of this was designed to provoke a British reaction and full-scale war. Fortunately, neither London nor Washington had any interest in conflict and both stayed their hands.

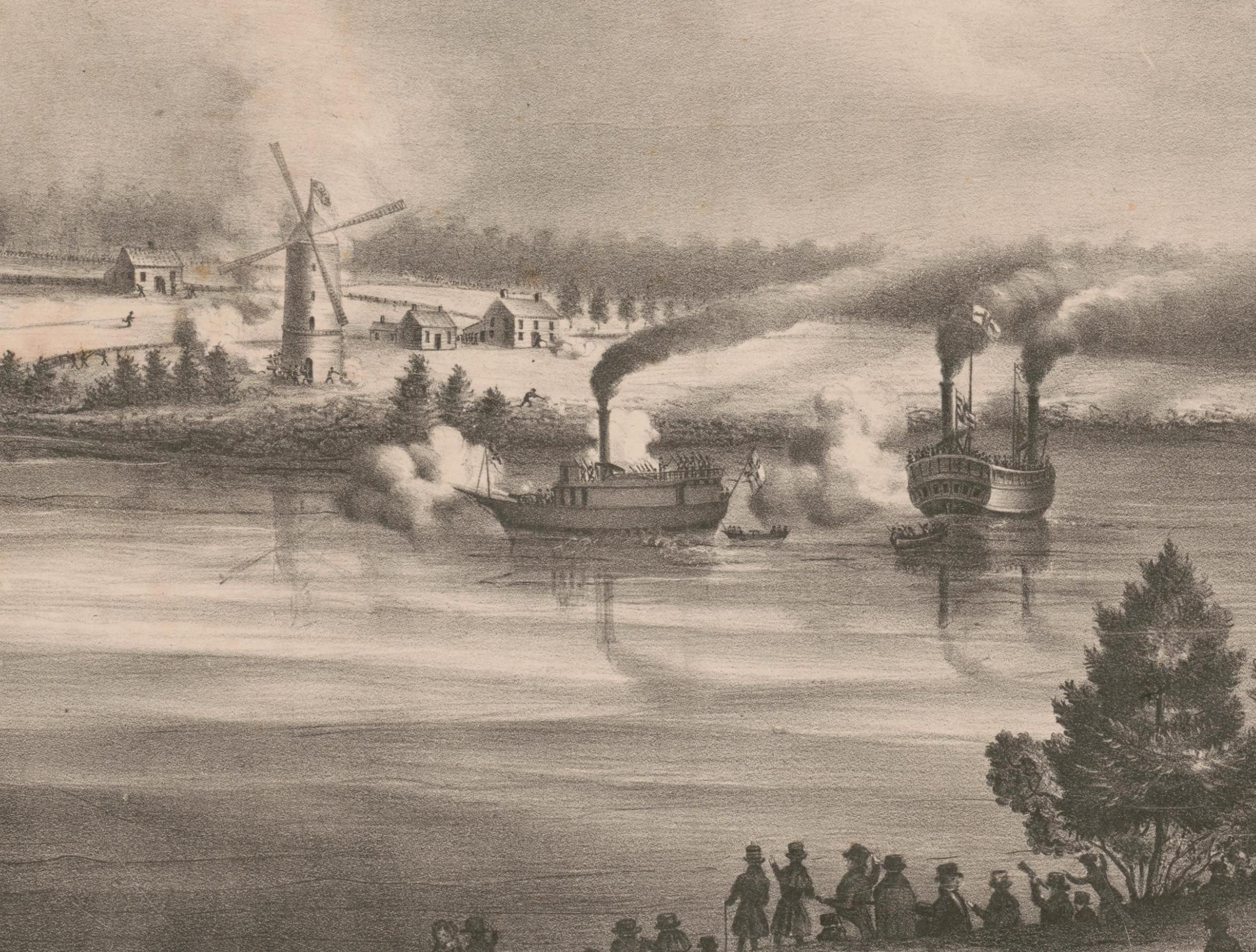

At last, in the autumn of 1838, the Hunters’ Lodges decided to risk everything on an all-out attack on Upper Canada. Their chief target was the little town of Prescott on the St Lawrence River, home to a crucial supply base at Fort Wellington. This, they hoped, would be the beachhead for an invasion.

Unexpectedly, the key figure in this adventure was neither Canadian nor American but the Finnish-born son of a Swedish official. Born in 1807, Nils von Schoultz had already enjoyed an extraordinary career. Having resigned from the Swedish army over his gambling debts, he had fought for Polish revolutionaries against the Russians, joined the French Foreign Legion and taken part in the invasion of Algeria.

Returning to Sweden, he opened a laboratory and tried to market a new red dye, before moving to New York and inventing his own process for extracting salt from brine. All this by the age of 30. To the idealistic Von Schoultz, the Canadians were the Poles of North America, cruelly oppressed by their tyrannical overlords. So at dawn on November 12, 1838, he joined hundreds of men to cross the St Lawrence, eager to light the fire of revolution.

The result was a catastrophe. Most of the rebels never made it to Prescott since their boats ran aground on the mud flats. Worse, British agents had infiltrated the lodges, so their border troops were primed for battle.

In desperation, Von Schoultz rallied some 250 rebels to establish a base in a stone windmill. For five days they held out under punishing British fire. But as food ran out and the death toll mounted to 50, even Von Schoultz recognised that the game was up, and on the evening of November 16 he surrendered. By the standards of the day, the British response was remarkably mild. Of the survivors, more than 100 were immediately set free or later pardoned — but 60 were transported to Australia and 11 of the ringleaders were executed, including Von Schoultz.

The tragic irony is that his British adversaries, impressed by his courage, wanted to see Von Schoultz pardoned too. But at his court martial the Swedish adventurer insisted that he deserved to be punished. He had made a terrible mistake, he said. It was obvious the Canadians were perfectly happy as they were and he must pay the ultimate price.

Spectators in the foreground watch the Battle of Windmill Point, near Prescott, upper Canada, in 1838

ALAMY

Whether Donald Trump would respect such self-sacrificial gallantry is very dubious. Still, he really ought to reflect on the story of the Battle of the Windmill. For among the few iron-clad lessons of history, one stands out. Try as you might, you will never force the tax-paying, law-abiding people of Canada to become Americans. After all, why would they want to?