For several decades, a captivating theory has been circulating: that according to which the remains of Arsinoe IV, a Ptolemaic princess murdered by her older sister Cleopatra VII, were found in a sumptuous funerary monument in the ancient city of Ephesus.

An interdisciplinary team from the University of Vienna (Austria), in collaboration with experts from the Austrian Academy of Sciences, has just debunked the myth by revealing the real identity of the deceased. According to their work, published in Scientific Reports on January 10, 2024, the tomb actually contained the skeleton of a young Roman suffering from developmental disorders. Discoveries which relaunch the quest for the true remains of Arsinoe IV.

Mysterious prestigious tomb in Ephesus

Founded in the 10th century BC. BC, the ancient Greek city of Ephesus (west coast of Anatolia, present-day Turkey) was not only home to one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, the temple of Artemis. Sacred road to the famous building and major artery of the city, the rue des Curètes (or Courètes, priests responsible for the administration of the temple) was littered with large buildings, each more sumptuous than the other. In particular, a funerary monument called “the Octagon” by archaeologists because of its shape.

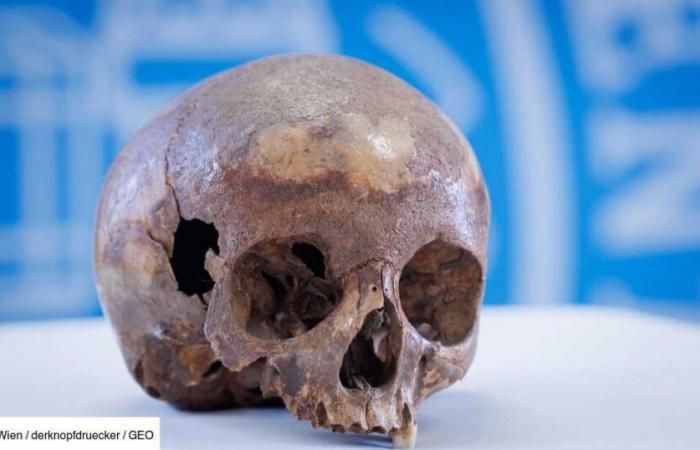

The style of its motifs suggests that it was built in the second half of the 1st century BC. BC, perhaps during the reign of Augustus. In 1929, the Austrian archaeologist Josef Keil discovered, in its ruins, a sarcophagus filled with water from which he removed a skull. It belongs, according to initial analyses, to a “high-ranking” woman of around 20 years old. A first hypothesis supported by the Austrian anthropologist Josef Weninger, who published an article in 1953 describing her as an “aristocrat of Antiquity”.

In 1982, excavations revealed the rest of the skeleton, in a niche located in the antechamber of the sumptuous tomb, sometimes described as a heroon (monument erected in memory of a hero). In the 1990s, the theory was born according to which these remains could belong to Arsinoe IV (68-41 BC), Egyptian princess and queen of the Ptolemaic dynasty and youngest sister of the famous Cleopatra VII.

In a struggle for the throne of Egypt, the two sisters face each other. Arsinoe IV allied himself with his brother Ptolemy XIII, Cleopatra VII with Julius Caesar. After the defeat of her camp during the siege of Alexandria (48-47 BC), the first was taken to Rome as a prisoner. She is, however, spared and allowed to live in the temple of Artemis in Ephesus. A short-term exile: Cleopatra, wishing to eliminate a potential rival, persuades Marc Antony to have her executed, despite the sacred nature of her refuge.

-Not Arsinoe IV, but a young Roman nobleman

These historical accounts according to which Arsinoe IV was assassinated in Ephesus in 41 BC. BC, as well as the architecture of the Octagon, influenced by Egyptian models, led experts to believe that she could have been buried there. But the hypothesis nevertheless remained speculative, due to the absence of conclusive material evidence, such as DNA analyzes or inscriptions formally identifying the remains.

The study by the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology at the University of Vienna finally makes it possible to completely rule out this long-standing theory. Certainly, the various analyzes recently carried out on the skeletal remains of the Octagon allow them to be dated between 205 and 36 BC. BC, which agrees with the supposed date of the death of Arsinoe IV. Genetic testing, however, revealed a surprise: the associated skull and femur clearly showed the presence of a Y chromosome; they belonged to a boy.

Morphological analyzes and computed tomography (CT-scan) data confirmed that this individual, aged 11 to 14, was still in full puberty. And that he suffered from major pathological disorders. In particular, premature fusion of a cranial suture, an abnormal phenomenon where the joints of the skull fuse too early – they normally remain open until an advanced age (around 65 years or more). This condition distorted his skull, causing asymmetry and facial growth abnormalities. His upper jaw, underdeveloped and tilted downward, caused great difficulty in chewing – this is further evidenced by observations on his teeth.

According to researchers, a vitamin D deficiency or a genetic pathology (such as Treacher Collins syndrome) could explain these anomalies. Regardless, it is now established that the Octagon burial in Ephesus did not hide the remains of Arsinoe IV, but of a high-ranking young man with developmental disabilities of Roman origin – Italian or Sardinian, suggested genetic analyses.

The architectural references to Egypt on the Ephesian monument remain mysterious. “The results of this study thus open new avenues for exciting research, and the quest for the remains of Arsinoe IV can now continue without being hindered by speculation”conclude its authors in a press release.