⇧ [VIDÉO] You might also like this partner content

A group of biologists has uncovered a primitive single-celled organism that forms a cluster of cells with striking similarities to an animal embryo when it reproduces. This indicates that embryonic development could have existed well before the appearance of the first animals, providing a potential answer to the famous chicken-and-egg paradox – the egg would therefore have appeared first, according to this discovery.

The evolution of multicellular organisms from unicellular organisms constitutes a major step in the history of life on Earth. Multicellular organisms have evolved highly specialized capabilities allowing them to flourish from a single cell (the egg cell) to form an entire, complex organism. This includes the generation of different cell types, the formation of three-dimensional tissues and the establishment of a precise blueprint for the structuring of the body.

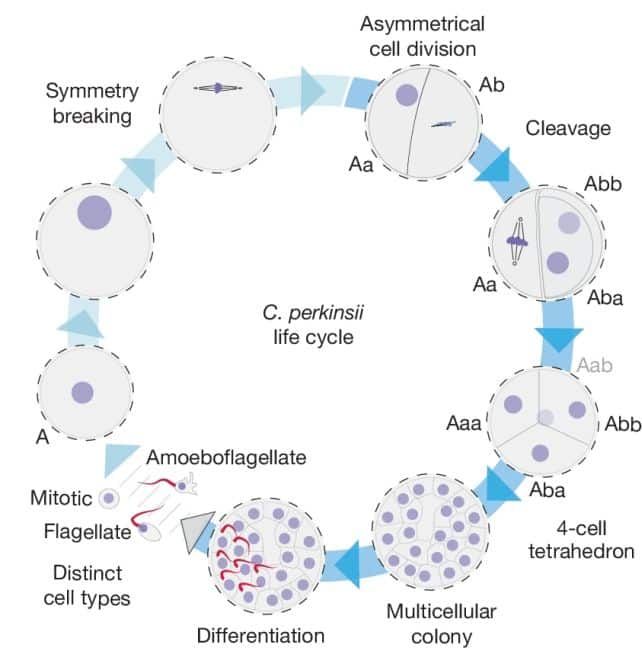

During embryogenesis in animals, several processes following a very precise chronological order take place, notably cleavage (the cells divide rapidly, but do not grow), the establishment of the embryonic axis, the activation of the zygotic genome and the spatial organization of the layers of germ cells which will form the different organs and parts of the body.

The T-Shirt that breathes:

Display a powerful climate message ????

This sequence is common to all animal species and could date back to a period before their appearance. Paleontological studies have shown that fossils of single-celled organisms dating back more than 600 million years have morphological characteristics similar to those of animal embryos. It has therefore been suggested that these groups constitute the single-celled strains of all animals. This hypothesis is, however, the subject of debate and the transition from multicellular organisms to unicellular ones remains largely unknown.

A new study from the University of Geneva and the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) suggests that ichthyosporeans, primitive single-celled organisms found in marine sediments, could be excellent models for studying this transition . Although they are not categorized as animals, they have many similarities with animals.

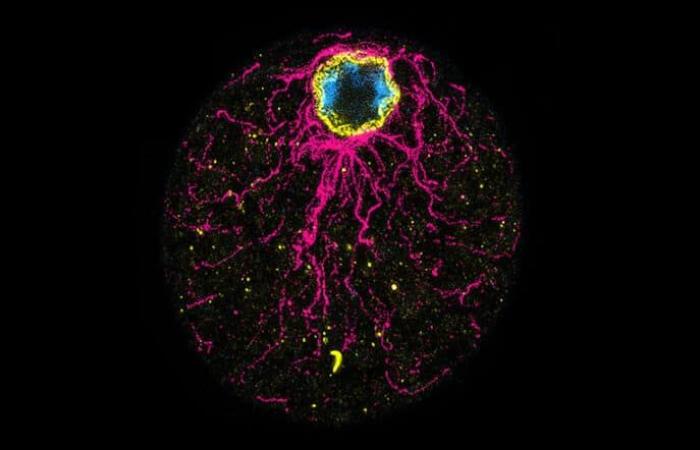

A cell of the ichthyosporean C. perkinsii showing distinct signs of polarity, with clear localization of the nucleus before the first cleavage. Microtubules are shown in magenta, DNA in blue, and the nuclear envelope in yellow. © DudinLab

Striking similarities with animal embryos

The new study team focused on

Chromosphaera perkinsiian ichthyosporean discovered in 2017 in marine sediments around the Hawaiian archipelago. Paleontological records have shown that these organisms appeared more than a billion years ago, long before the appearance of the first animals.

By studying the life cycle of C. perkinsiithe researchers found that once they reached their maximum size, the parent cells actively divided, but without growing any further. That is, they undergo mitosis associated with cleavage, a process known as palintomy in animal embryos. “ This finding suggests that C. perkinsii proliferates through a palintomic mode of development, highlighting the wide range of cellular and developmental diversity within the Ichthyosporea », they explain in their document, published in the journal Nature.

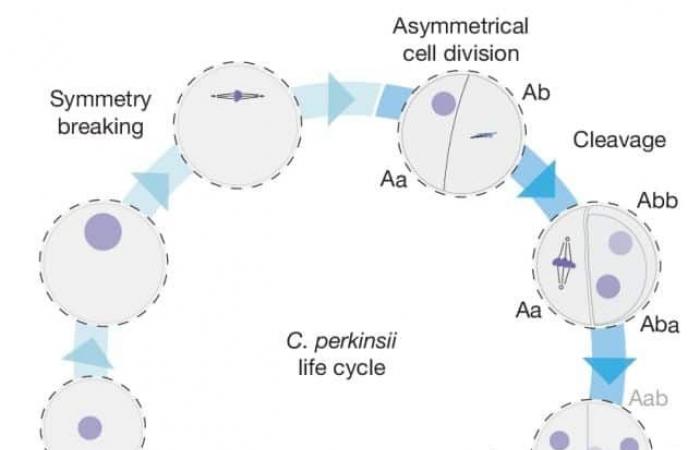

Life cycle of C. perkinsii. © Olivetti et al.

This mechanism gives rise to multicellular colonies with striking similarities to blastulas, hollow clusters of cells formed during animal embryogenesis. “ Although C. perkinsii is a unicellular species, this behavior shows that multicellular coordination and differentiation processes are already present in the species, long before the first animals appeared on Earth », Explains Omaya Dudin of EPFL, who led the research, in a press release from the University of Geneva.

See also

Even more astonishing, these colonies persist for about a third of the organism’s life cycle and include at least two distinct cell types, which is surprising for a single-celled organism. The cells then eventually disperse to become independent organisms. The analysis of genetic activity within the cell clusters also showed similarities with that occurring in animal embryos.

These results suggest that the genetics governing complex multicellular development were already present more than a billion years ago. In other words, the genetics responsible for embryonic development were already present before the divergence of the first animals from single-cell lineages. Nature therefore already had the genetic tools necessary to create “eggs” well before the appearance of “chickens”.

However, it is also possible that this trait evolved independently in C. perkinsii and was not inherited from a common ancestor of ichthyosporeans (evolutionary convergence). More research will be needed to determine the exact origin of the phenomenon. Nevertheless, this discovery could end the debate regarding animal stem groups and challenge traditional theories about the evolution of multicellular lineages.