It was December 27, 1974. 42 miners were killed by a blast of firedamp in Liévin, 710 meters underground, in one of the most tragic mining disasters in French history. Among them, Paul, whose son Michel, even 50 years later, cannot hold back his tears when talking about the tragedy. A documentary film dedicated to the descendants of the victims will be broadcast on our channel on January 16, 2025.

The essentials of the day: our exclusive selection

Every day, our editorial team reserves the best regional news for you. A selection just for you, to stay in touch with your regions.

France Télévisions uses your email address to send you the newsletter “Today’s essentials: our exclusive selection”. You can unsubscribe at any time via the link at the bottom of this newsletter. Our privacy policy

This December 27, 2024, like every year for fifty years, a tribute will be paid to the 42 victims of the Liévin mining disaster. A ceremony “solemn and a little different“, as requested by the city’s mayor, Laurent Duporge. On the program, the inauguration of a commemorative fresco, the preview broadcast of a documentary and the lighting of a flame, in memory of the disappeared.

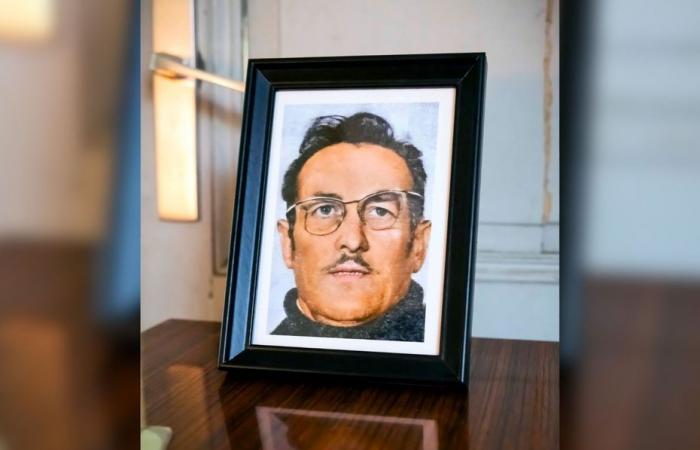

Among them, Paul Vandenabeele. He was a prop inspector, supports used to support the ceiling of galleries in mines. This morning of December 27, 1974, he resumed work in the Saint-Amé pit, after having celebrated Christmas with his family on the 25th and 26th, Saint-Etienne’s Day, traditionally a non-working day. His wife asked him not to leave. He insisted on “end up with friends“. So he left. And he never came back.

Paul Vandenabeele is one of the 42 miners who disappeared in the Liévin disaster on December 27, 1974. His son testifies today in a documentary.

•

© Gaëtan Lamarque

Today, Michel is 67 years old, he is the ninth of Paul’s twelve children. “I was 16 and a half years old when the disaster happened.“, he remembers in a documentary film directed and produced by Germain and Robin Aguesse and soberly entitled The Liévin disaster. At the time, the young man was already working in construction, to help support the family.

“That day, I was in bad weather, the boss had told us to stay at home, because the weather was bad. When the disaster happened, I was there from start to finish.“, he says before stopping, moved. Michel keeps engraved in his head the last image he has of his living father. “I came down and he was there with his bag, ready to go to the pit with his moped. He had fifteen days left before retirement.”

Michel Vandenabeele was not yet 17 years old when his father died in the Saint-Amé pit on December 27, 1974, the victim of firedamp.

•

© Gaëtan Lamarque

“On Christmas Day, we had a good New Year’s Eve, we had a lot of fun, we danced, it was great. But on the 27th, he had to go back.” Shortly after six in the morning, 90 miners took up their posts to continue work in a gallery of 1 200 meters long. HAS 6:19 a.m., a dull noise resounded at the bottom of pit 3 (called Saint-Amé) of Headquarters 19 of the Lens mines in Liévin. 42 men will never see the light of day again.

Very quickly, Michel and his big brother, himself a miner at Avion, were there. “We saw empty coffins enter but immediately they closed the big door, we couldn’t see what we wanted.” The brothers end up entering, looking for their father, when they are told: “Vandenabeele? It’s over there, look, there’s the label on the coffin.”

When we told him he was dead, my mother collapsed.

Michel VandenabeeleDescendant of one of the victims of the Liévin disaster

“So we saw it. The fifth coffin was my father. At the bottom, there was a woman banging on a coffin and screaming. : « Come back, come back ! »and she shouted a name. We went home and told my mother. She fell. When we told her, she fell. And afterward, it was terrible.“

“We took our father home until the 31st. We didn’t want to leave him there. When I asked a rescuer what condition he was in, he wouldn’t answer me. We wanted to know if it was him who was in there. We always wonder.”

“Below the coffin, liquid was flowing. The lifeguard told me : « It’s because we washed them. We had to recognize them. ». There’s nothing to answer that.”

Tribute to the victims of the Liévin disaster of December 27, 1974.

•

© City of Liévin

Michel remembers the funeral, the ceremony, the “big try“, the chairs, the cold, the blanket that he had thought of taking to put on his mother’s legs. His mother that the Coal Mines would try to evict to get the house back, since she was not married. “She was ultimately able to keep it as long as she had young children. They had great courage, the widows. They were young. They were called merry widows.“, saddens Michel, who then became the breadwinner of the family.

Since then, he has carried with him immense sadness. “This is what struck me the most while making the film, confides Robin Aguesse, one of the two directors. When Michel tells his story, fifty years later, it is still with the same deep suffering..”

“The first time we met himcompletes his brother Germain, Michel was so moved that he couldn’t speak. As if the event had taken place the day before. So this film is necessary. So that the memory of those who experienced this tragedy does not fade away, so that the story of these minors does not fall into oblivion.“

Other descendants, as well as a miner’s widow, are interviewed in the documentary. For Annie Kubiki, whose gas worker father was one of the rare survivors, every December 27, the day repeats itself. “I see my front door, my little house, the table where I worked. I see the ambulances, this pit tile… It cannot become a memory, it remains present. It was an event that shocked our lives.”

These men, they existed, they worked, they gave their lives to their work. We must not forget.

Micheline LhermiteWidow of one of the victims of the Liévin disaster

Micheline Lhermite’s husband was a pollster. Together they had five children. “I was 34 when he diedshe blurted out, trembling. He was 35. I got married at 17. It was a first love… All the little ones who arrive must know that they had a grandfather who was killed at the Coal Mines. These men, they existed, they worked, they gave their lives to their work. We must not forget.“

It is for this duty of memory that the film exists. It will be broadcast in preview to the families of the victims on December 27, 2024 at 5:30 p.m. at the Pathé cinema in Liévin, then on France 3 Hauts-de-France on January 16, 2025 at 10:50 p.m.

It is also for “don’t forget” that André Verez, son of one of the eight survivors of the disaster and president of the Association of December 27, 1974, wanted to make this fiftieth anniversary a particularly strong moment. For months, he worked to find the families of the 42 missing.

“I wanted to honor the children, the grandchildren, the great-grandchildren. We didn’t find everyone, but I would say at least 70%. We wanted to be involved in this commemoration. So it is we who will carry the portraits of the victims. For our families, it happened yesterday, we still live with this pain and we do not want this disaster to be forgotten.“

Of course, as I always say, I was lucky to keep my father. But was my father lucky to survive? He was a broken man.

André VerezPresident of the Association of December 27, 1974

The man’s name is André, like his father. He has very hard memories of that day. “But also the months and years that followed. Of course, as I always say, I was lucky to keep my father. But my father, heWas he lucky to survive? ? With the physical and psychological aftereffects… He was a broken man.”

A huge fresco, painted entirely with a brush, was created in tribute to the deceased by the artist Rouge Hartley on a Liévin residence managed by Pas-de-Calais Habitat, in the heart of the Saint-Amé district. It will be inaugurated on December 27 at 10 hours.

“Rouge Hartley met the victims’ families and consulted the archives of Liévin and the Lewarde mining museum, to immerse herself in the history. She also worked with students from the Léo-Lagrange school“, specifies Katy Clément, school assistant.

The fresco in tribute to the 42 victims of the Liévin mining disaster was entirely painted with a brush by the artist Rouge Hartley. It will be inaugurated on December 27, 2024, fifty years after the tragedy.

•

© Pas-de-Calais Habitat

The social landlord, who is keen to “pay tribute to these courageous men, whose work and sacrifice shaped the industrial and human history of our territory“, also gave voice to the Liévinois in a work entitled Lives. 42 keywords in memory of the 42 who died, from lighters to solidarity, including coop and brass band.

Michel Vandenabeele, he, testifies to his father’s passion for columbophilia. “My father had a beautiful dovecote that had to be cleaned every day. It was imperative to take good care of the birds, to ensure that they had something to eat and drink. We also had other animals: rabbits and chickens. As my father worked in the mine, my brothers and I were often on duty to take care of it..”

The laughter of a joyful childhood alongside Paul continues to resonate in Michel’s heart, 50 years after the disaster. “The memory I have of my father is when I was a little younger. We played with him. Like all fathers do with their children. We climbed on his back, then he walked on all fours on the tiles, he went around the table. Those were good memories. And then there were especially Christmases. Sometimes he was the one who dressed as Santa Claus, but we didn’t know that.”

“We didn’t have much. An orange, a brioche, a small square of chocolate. We weren’t very rich, but we were happy.“Everything is said.