The Innu community of Pessamit is located approximately 50 kilometers southwest of Baie-Comeau on the North Shore. In a seven-episode podcast put online a few weeks ago, nine local elders recount their youthful memories when, as children, they accompanied their parents on their seasonal trips to the ancestral territory, the Nitassinan.

Every year, at the end of summer, they left for long months, traveling by canoe along the rivers between the coast of the St. Lawrence River to their ancestral territory where they settled for winter hunting. . However, from the 1950s, the construction of the first hydroelectric infrastructures ended up hindering canoe routes. Ultimately, the dams submerged the traces of Innu passages under water and concrete, such as temporary villages and cemeteries, along the Pessamiu Shipu and Manikuakanishtik rivers.u that Ticket connectoru.

“I started my doctorate about 10 years ago and I met several elders from Pessamit, the last of whom had experienced nomadic life on the territory as well as its transformation through hydroelectric development,” explains the Professor Justine Gagnon, from the Department of Geography at Laval University and scientific manager at the Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Heritage and Tourism.

“These people,” she emphasizes, “had a deep attachment to the rivers, which were the entry routes to circulate in the ancestral territory. When I became a professor, a grant allowed me to work on the Innu heritage associated with rivers, in particular the Manicouagan River. We said to ourselves that we had to find a way to make the words of the elders of Pessamit more accessible. It was from there that a podcast project took shape. It was supported by the director Jean-Luc Kanapé, an Innu from Pessamit, the designer, screenwriter and director Karine Lanoie-Brien and the production companies Terre Innue and Innu Assi. My role during the project was that of consultant-researcher.”

Survey maps, aerial photos

For her doctorate, Professor Gagnon did a lot of digging in the archives. She also studied a lot of old maps, including old survey maps on which several portage routes were identified. “I was able to provide a certain amount of information,” she said. During my studies, I did a lot of work digitizing old aerial photos of rivers. My work upstream really created a knowledge base.”

The traces left by the Innu on the territory took, among other things, the form of temporary camps where families stopped after a certain number of kilometers to rest. On the hunting territory, several cabins or tents were used for housing and storage of equipment. In their testimonies, the elders speak of villages made up of several cabins per family.

Large hunts to track game could last for weeks.

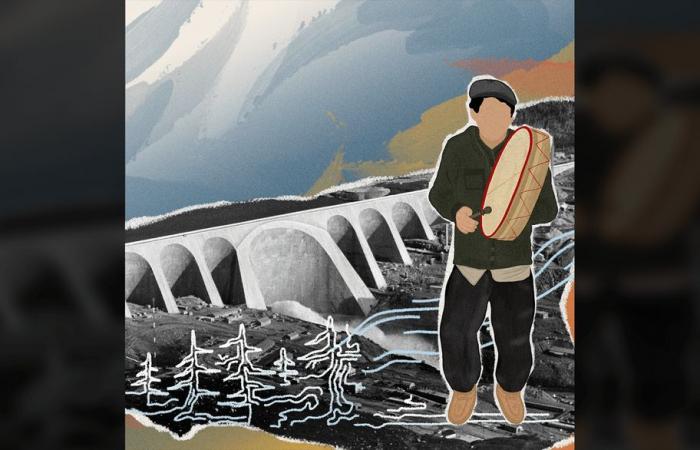

— Mali Rock-Hervieux (illustration), Sarah Warren (collage with incorporation of visual archives)

“On the route,” she continues, “they crossed portage paths to bypass falls and rapids that they could not cross with their loaded canoes. These trails were marked by notches in trees. All of these elements of Innu cultural heritage have, for the most part, disappeared. Of course there were births; there were also deaths during these long annual journeys. Places were used as burial sites to bury the bodies. I know that a certain number of graves were able to be repatriated before the flooding, but not all. Ancestors are under the water.”

Nine testimonies

Nine elders from Pessamit provide first-hand accounts during the approximately 200 minutes of the podcast. Under the dams: Tshishe Manikuan. From one episode to another, the elders focus on the Manikuakanishtik Riveruor Manicouagan. “The team gave a special place to the knowledge of women, their experiences, their perspective on this history,” indicates Justine Gagnon. They gave birth on the territory. It’s difficult to imagine that today, what physical and mental strength it took to live in the territory.”

Another episode is devoted to a period of famine when game was scarce. “As for the seventh and final episode,” she explains, “it is very beautiful, I would say overwhelming. Jean-Luc Kanapé leaves with two young Innu and an elder to go to the site of a former portage near the Manic 5 hydroelectric complex. It is overwhelming to hear these voices of young people today who, often, do not don’t know much about their culture. At the same time, knowledge continues to be transmitted despite everything.”

The traditional way of life of the Innu of Pessamit was disrupted with the construction of hydroelectric dams.

— Mali Rock-Hervieux (illustration), Sarah Warren (collage with incorporation of visual archives)

Evocative titles

The listener will be able to listen to stories with titles as evocative as “The call of the Great North”, “In the footsteps of our ancestors”, “Giving life and helping each other”, “At the heart of our way of life”, “The wisdom of survival”, “The song of return” and “The destruction of the territory”. The Innu elders recount in particular the departure by canoe from the beach of Pessamit to reach the ancestral territory, the portage in order to bypass high falls while walking in the footsteps of the ancestors, the hunting camp where the women arranged the skins of the game killed by their husbands to sell on their return, and life on the hunting ground which required knowing how to give birth, take care of themselves, and do everything by themselves.

The podcast is available in the original French version and in the Innu-Aimun version. It includes a musical theme, musical pieces, audio archives. The official launch took place on the - OHdio platform.

“So far,” emphasizes Professor Gagnon, “we have only received laudatory comments, whether from non-natives or natives. It is certain that when the people of Pessamit demonstrate the importance of this work for their young people, the podcast project takes on its full meaning. We can’t hope for better.”