The site of Missignac, a villa from the 5th to 13th centuries, was identified in 1995 thanks to archival records and the discovery of its attics.

Vertical view of a bread oven from the village of Saint-Gilles-de-Missignac, early Middle Ages, Aimargues in 2012 (Photo Archives Jérôme Hernandez, Inrap)

THE works on the railway bypass of the High Speed Line between Nîmes and Montpellieraround ten years ago, was a good opportunity to highlight the forgotten stories of the territory. Here, we are on the Aimargues side.

The medieval villa is a type of habitat little known to historians and still little documented in Languedoc by archaeology. The excavation, carried out over nearly two hectares by a team of 15 to 45 archaeologists, uncovered and deciphered, over eight and a half months, the interweaving of the remains of the church, around 80 houses, the cemetery ( 850 deceased) and 450 grain pits from the vast silage area.

In addition to characterizing the forms of housing, the economy of the site on its land, its population and its culture, the objective of the intervention was to shed light on the intermediate stages between the end of the ancient villa and the birth of the castle town.

Change in habitat between Antiquity and the Middle Ages

The discovery of ditches in the protohistoric and ancient plot indicates that the Missignac land has been occupied since the Iron Age. From the 1st century AD, it was structured and operated as part of an estate whose villa was outside the excavation area, towards the west.

Its existence can be restored by the presence, in the ditch which encloses it, of its occupants' trash cans. In the two excavation areas, part of its terroir is revealed: against the enclosure of the villa are the small plots reserved for livestock for local grazing, milking and shearing, beyond there grow a large vineyard and further still meadows and cultivated fields.

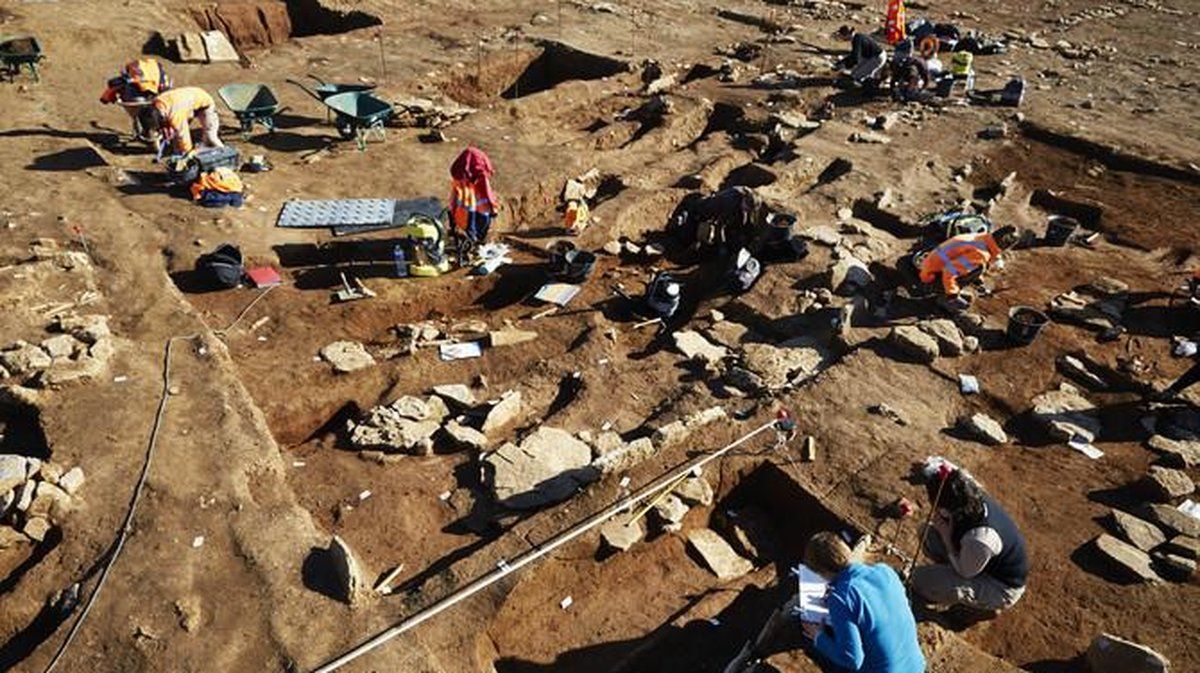

The archaeological excavation of Aimargues (Photo Archives Yannick Brossard, Inrap)

In the 5th century, the ancient villa was no longer the only place of residence for the operators. Some of them settled in its neighborhood, on the old vineyard plot and then beyond. Six of these farms have been identified.

The first dates back to the second half of the 5th century and is located in the south. The others, more recent, were installed first in the northwest then in the northeast, obviously along a path outside the excavation limits.

Of these first installations, as of most of the following ones, only the deepest structures remain, that is to say the cellars of the houses which were equipped with them, the pit of the crawl spaces under the floors which have disappeared, the cleared floors of the stables, the wells, the silos and some of the drainage ditches.

The number of buildings was greater than observed and the complete plan of the site is not known. However, we observe the loose agglomeration of buildings which are grouped on plots whose orientation differs depending on the neighborhood.

The buildings are associated with reserves: cellars especially until the 7th or 9th century and silos preferably afterwards. Courtyards and gardens were integrated into the built landscape while beyond that the cattle enclosures of the west persist and other small pieces of land emerged to the south-west.

Genesis and evolution of the village

At the end of the 7th century, we witnessed the development of a funerary space then, in the 9th century, the densification of the habitat. Both phenomena seem to start in the north, along a regional road. The burials gradually reach the south in small groups associated with larger farms. Courtyard and garden space is reduced, which leads to the installation of storage pits for cereal harvests outside the village, in the former western residential area.

The archaeological excavation of Aimargues (Photo Archives Yannick Brossard, Inrap)

There are hundreds of them, distributed in groups separated by paths, and associated with areas for unloading, drying and probably still hulling the grains.

During the 10th century, a church was built on the site. The foundation of its flat apse and the melting furnace of its bell were found in place. From then on, tombs and houses were concentrated around the building. The densification which continued until the beginning of the 12th century gave the village another aspect; centered around its bell tower. With demographic and undoubtedly economic dynamism helping, the church was enlarged, perhaps then dedicated to Saint-Gilles (sancti Egidii, a term which may have been his from the beginning) and equipped with a new bell.

During the second half of the 12th century, the buildings gradually became sparse again: the inhabitants left the village, which was described as “old” from 1202 (villa sancti Egiddi veteris); it is then abandoned. Its bell was quickly recovered and the facade of the church dismembered, but people continued to be buried in front of it until the beginning of the 13th century, just as some silos remained in use on the storage area. The sector became agricultural again around 1225; Wheat was cultivated there in the 14th century.

Ways of living and living

The living environment of the inhabitants of Saint-Gilles de Missignac is reflected through the remains of their habitat and the furniture found either reused in buildings or in some silos which served as a dump after their abandonment. The houses are mainly built of earth, sometimes from the foundation.

Excavation of the second cemetery near the village church of Saint-Gilles-de-Missignac, 9th-13th century, Aimargues in 2012. Within this funerary space nearly 400 individuals were buried (Photo Archives Yannick Brossard, Inrap)

They consist of a ground floor undoubtedly topped by a floor serving as a hayloft or attic. The covering had to be most often made of plants: thatches, the supply of which is facilitated by the proximity of ponds. However, some buildings have a stone base and a tiled roof. Some houses only have one room. Most have two. More than three is exceptional; in this case, a room may have served as a stable.

Abundant and very varied in the 5th century, domestic furniture became much rarer and more uniform thereafter. We mainly find globular pots serving as jugs and pots, in gray ceramic, sometimes decorated with small incisions. It is possible that most of the tableware was made of wood.

The tools unearthed are mainly agricultural and to a lesser extent artisanal. In addition to a quantity of weaving weights and two sickles, a large number of maies and grain millstones were unearthed. Some coins and objects originating or not from the region show that the villagers participated directly or indirectly in exchanges over long distances.

Their living conditions were, however, difficult: the study of the skeletons shows that a significant number of inhabitants were exposed to malnutrition or suffered from infectious diseases. Nevertheless, the Missignacais lived quite old, not being rare to exceed eighty years.