I have spent much of my career studying crime trends and explaining the significant declines in violence that followed the tumultuous 1970s.

Published at 1:52 a.m.

Updated at 11:00 a.m.

Marc Ouimet

Retired professor of criminology

Among the major explanations for the decline in crime between 1980 and 2010 are factors such as demographics (fewer young people), the economy (more jobs for young adults), routine activities (more time spent at home in front of a screen), education (more young people involved in school programs), pharmacology (the arrival of new antidepressants), changing social values (an increase in tolerance and compassion towards loved ones), the deployment of more targeted and effective treatments for justice clients (anger management, drug addiction), greater reporting of domestic or sexual violence, the gradual disappearance of the use of cash and the drop in the cost of purchasing electronic equipment and tools making burglaries less attractive.

Also, spectacular developments in technology have certainly contributed to the drop in crime: the deployment of thousands of surveillance cameras, advances in DNA, access to real-time data by police officers during interventions, tracking our movements and activities via our phones, etc.

More indelible traces equal higher risks of apprehension, and therefore a reduction in crime.

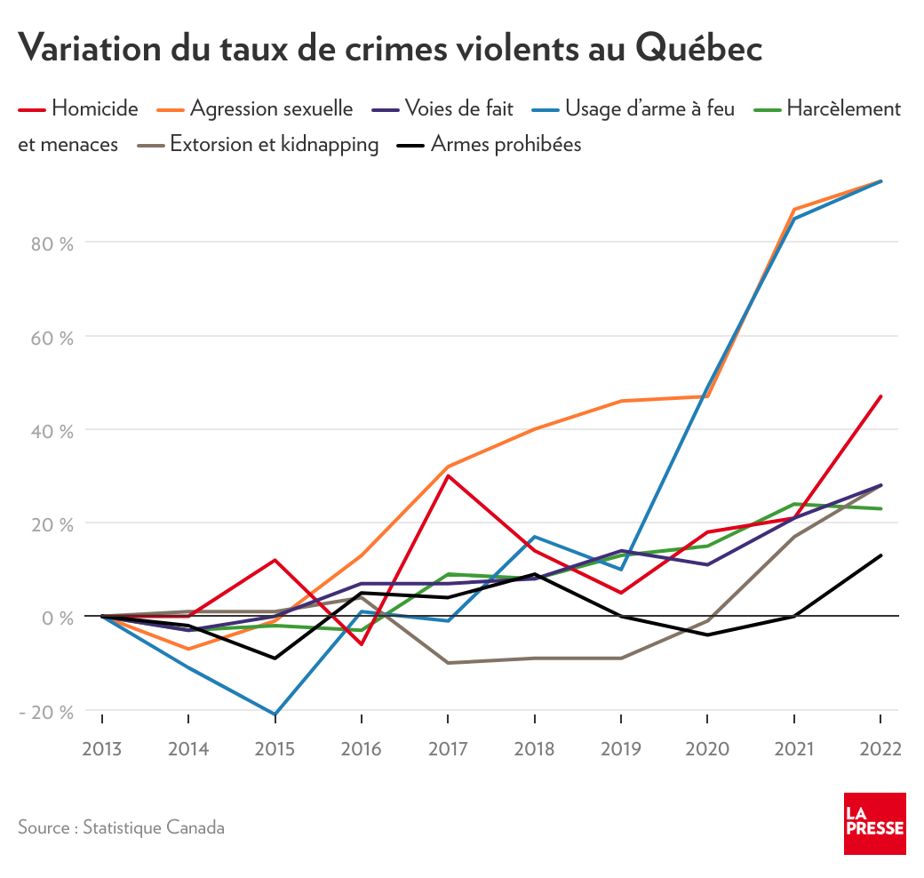

However, for several years, surveys and journalistic articles have indicated a growing concern among the population about its sense of security. And official statistics from Statistics Canada clearly reflect a significant increase in violence in recent years. The following figure that we have developed illustrates the trends in the different forms of violent crime in Quebec over the last nine years, with 2013 serving as a reference point.

We have omitted the trends for robbery, which is the only violent crime that has decreased (by 33%), a decline that can be explained by the gradual abandonment of the use of cash, both among citizens and in businesses.

All forms of violent crime have been increasing since 2016 and we can see that the increase had started before the years 2020-2021, which casts doubt on the “pandemic” explanation of the increase.

Since 2013, possession of prohibited weapons has increased by 13%, harassment and threats by 23%, extortion and restraint of liberty and assault by 28%, homicide by 47% and sexual assault and use of firearms (displaying, pointing or discharging) by 93%.

It is noteworthy that trends in absolute crime numbers show even larger increases (21% for weapons, 32% for harassment, 37% for assault and extortion, 57% for homicide, and 107% for sexual assault and firearm use).

The causes

But how can we explain such an increase in violence? On the one hand, the scientific literature on the new increase, observed in English Canada and the United States, is starving. On the other hand, the data collected by the police on criminal events would at least allow us to identify for what kind of people, in what kind of situation, we observe significant increases. The data is available, we just need to use it. However, this work of detailed analysis is not done by anyone. Thus, knowing the situations on the rise would allow us to consider solutions; simply talking about housing or inflation will not change anything about the increase as long as we cannot diagnose the problem.

What would be the explanatory hypotheses? For me, it is unlikely that the use of violence is more frequent from year to year in the vast majority of the population.

The most likely scenario is that there has been a rapid increase in the number of people who find themselves living on the margins of society.

The possible reasons for a move “to the margins” are multiple, but surely have to do with economic exclusion and inflation, perhaps immigration, but above all with a growth in substance abuse and problems mental health. In particular, the recent arrival of synthetic opioid drugs like fentanyl is changing the situation.

The solutions

What could we do? Of course, we need to improve the last resort services offered to citizens in difficulty, increase the supply of social housing and provide easier access to drug addiction and mental health care. But we also need to take action with the many people who are resistant to intervention – who refuse all forms of help and treatment – and who commit violent acts, most often against other people in difficulty.

Action involves revitalizing police services (giving police officers the means to act), reframing the role of the Mental Disorders Review Commission and more appropriate use of criminal courts and correctional services ( which also show astonishing declines in prison populations in recent years).

It may also be time to review the sacrosanct principle that a person must accept the treatment offered to them; between the “Saint-Jean-de-Dieu” era and the current situation on rue Sainte-Catherine in the village, there may be a happy medium. The fact remains that we must act energetically to stem this new phenomenon that is creating insecurity among thousands of citizens, especially those who live in economically disadvantaged environments. And this new heavy trend of violence, if nothing is done, is likely to continue.

What do you think ? Participate in the dialogue