At the tip of the Île de la Cité, in the shadow of Notre-Dame, is nestled the masterpiece of Georges-Henri Pingusson (1894-1978), the Memorial to the French Martyrs of the Deportation. A creation as discreet as its creator and which well symbolizes its place in French modern architecture of the last century: capital, but little-known. This project also demonstrates a personal method, which questions the program upstream, adapts and transforms it, to access what Pingusson calls the “poetic transcendence of the concrete”.

First steps in architecture

More than thirty years before this accomplishment, his career began on sunnier shores and in a less solemn register. Indeed, the young Pingusson, associated with the architect Paul Furiet (1898-1932), built in the 1920s a series of regionalist or Art Deco style villas on the Côte d'Azur and in the Basque Country. He took care to conceal this youthful production when, at the start of the following decade, he resolutely joined the Modern Movement.

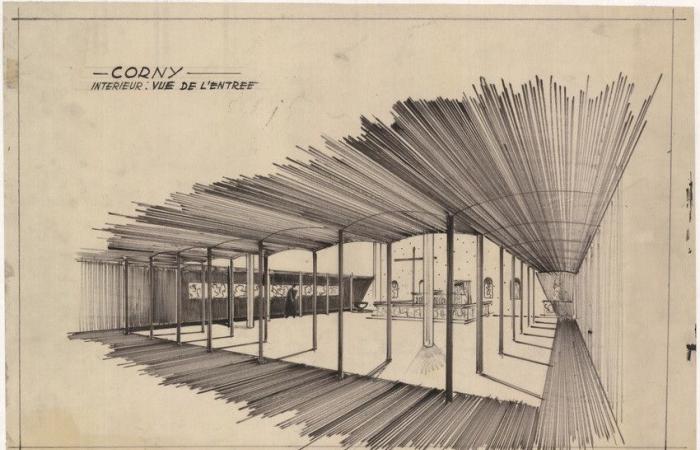

Perspective of the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin, Fleury, 1956-1963, contemporary architecture archives/City of Architecture and Heritage.

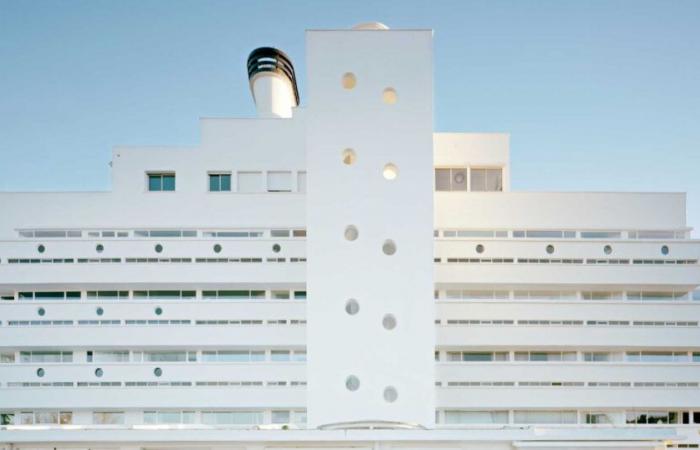

The construction of the Latitude 43 hotel (1931-1932) in Saint-Tropez then marked the thunderous irruption of the practitioner on the French architectural scene. Before tackling this project, the architect had already made a name for himself with the Théâtre des Menus-Plaisirs (1930), rue Pierre-Fontaine in Paris, where, on the blind facade pierced with portholes, the projectionist's cabin jutted out like the bow of a ship.

A new liner style

In Saint-Tropez, the reference to the liner appears less superficial. In this hotel designed as a refuge for artists and intellectuals, Pingusson operates a strict zoning between the different functions (residence, public spaces, services), a trait that transatlantic ships share with modern doctrines. In a more original way, he transposed the principle of the passageway into his project to offer the rooms a double exposure. The loggia on the south side meets the north with a panoramic view, made possible by the mid-level insertion of the service passageways. After the war, the architect used this same device in a school group in Boulogne-Billancourt, giving an unexpected heritage to the Paquebot style.

Latitude 43, Saint-Tropez, early 1930s ©Philippe Conti.

As historian Simon Texier points out, the Latitude 43 “did not embody nor correspond to any specific trend in contemporary architecture”as far removed from the purism of Le Corbusier as from the structural rationalism of Auguste Perret. Pingusson himself was aware of this singular position, as he expressed it in his Memoirs: “One cannot attach to my name a form of narrow doctrine, nor a system, I was neither a militant functionalist nor an expressionist who reduced the finality of architecture to plastic alone, because I saw in the form the outcome of a complex chemistry where all the components had brought their distillation, their perfume.”

The UAM manifesto

After the coup in Saint-Tropez, Pingusson relied heavily on the 1937 International Exhibition in Paris to transform the essay. In collaboration with Mallet-Stevens in particular, he submitted ambitious projects as part of competitions organized by public authorities: Le Bourget airport, an Olympic stadium, the Maison de la radio and even modern art museums. So many proposals refused. And the architect was content to build, with Frantz-Philippe Jourdain (1876-1956) and André Louis (1903-1982), the pavilion of the Union of Modern Artists (UAM, 1929), whose smooth glass facade ran along the Seine and ended in the bow of a ship… In an event where a sort of modern classicism triumphs, embodied by the Trocadéro and Tokyo palaces, the UAM showcase asserts itself as one of the most radical, manifest proposals of an international style in France.

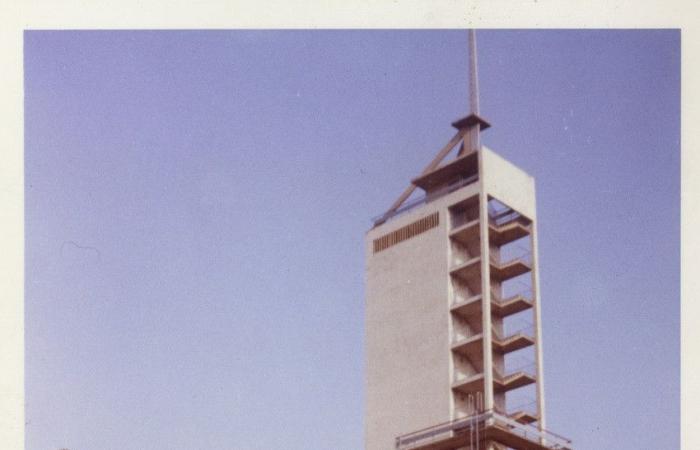

Drying tower, Firefighter intervention and rescue center, Metz, 1950-1965 ©DR.

After the Second World War, Reconstruction did not succeed much better in Pingusson. He joined the Moselle in 1947. Unfortunately, despite sustained activity, his urban projects remained in the form of models and only isolated buildings saw the light of day, here a school, there a fire station. In Briey-en-Forêt, Pingusson invited Le Corbusier to develop a model city. But the reputation of the latter helps to arouse opposition, particularly political, which will lead to the rejection of the mass plan. “Its failure in Moselle is that of functionalist urban planning”says Simon Texier. Ironically, Pingusson's few constructions in Briey are eclipsed by Le Corbusier's monumental Unité d'habitation. As if he were condemned to remain in the shadow of his illustrious contemporary.

Churches and a memorial

Unexpectedly, Pingusson's most significant contribution to reconstruction is related to religious architecture. At the end of the conflict, around forty churches had to be rebuilt in Moselle. And through the projects entrusted to him, the architect takes up the thoughts developed between the wars, particularly around the central plan. The Saint-Maximin church (1955-1966) in Boust thus borrows the main features of an aborted project for the Jesus-Worker church in Arcueil.

Interior view of the Saint-Maximin church, Boust, 1955-1966 ©Louis Panzani.

The audacity of his proposals appears more evident at the church of the Nativité-de-la-Vierge (1956-1963) in Fleury where, again, he recycles a sketch from the 1930s. “I don’t like the daylight that comes from above across the nave”he wrote in his preliminary notes. He therefore places the openings at ground level in a unique way in the raised nave, which seems to be bathed in “a light coming from nowhere”as Texier observes.

The Memorial to the Martyrs of the Deportation, Paris 4th arrondissement, 1962 ©ONACVG.

In these same years, Pingusson worked on his great work, the Memorial of the Martyrs of the Deportation (1953-1962), where his original approach ended up triumphing over all commissions. Refusing the facilities of a sculptural expression, he gives architecture alone the power to signify or, rather, to suggest the suffering endured by the deportees. Thus is born an invisible and paradoxical monument, archaic and radically modern at the same time, where the cyclopean masses of concrete enclose a void synonymous with absence. This twilight work embodies better than any other of his achievements what must be called an ethics of the architect, which was defined as “an independent creator, innovative and traditional at the same time, bringing to the artistic heritage of the architectural world a work apart, original and poetic, traditional, in the particular sense that I myself understood by this term, the sense of maintaining creative freedom to architecture with the desire to devote it to the happiness of man”.

“Georges-Henri Pingusson. A singular voice of the Modern Movement (1894-1978) »

at the church of the Trinitaires, 1, rue des Trinitaires, 57000 Metz

from September 18 to November 17

Georges Henri Pingusson exhibition by Simon Texier