Shaving cream, leather jacket, eau de Cologne or stew… What are the olfactory memories that revolve around our fathers? This is the question that Clara Muller invites us to ask ourselves in this personal and moving testimony, which we offer you on the occasion of Father’s Day – after Sarah Bouasse’s text for Mother’s Day.

I don’t remember my father ever wearing perfume. Or rather yes: I remember that on the very rare occasions when he sprinkled himself with the contents of an indefinite bottle evoking theafter shavesomething that seemed to me feel strangely wrong. As if it wasn’t really my dad standing there in that barbershop smell, but an imposter. Putting this fragrance on his person felt like cognitive dissonance, a glitch in the system. Of all the smells I associate with my father – and there are many – no perfume has ever had its place.

My father is above all the scent of morning coffee – ” Coffee ! » being almost always his first word upon waking up – which he systematically enhances with a drop of milk and very often a slice of Camembert or Roquefort happily dipped in the bowl. Coffee with milk and well-made cheeses are therefore the first scents that I associate with my father, because they were the first in my childhood and adolescence to accompany our days together, often with great expressions of disgust on the part from my mother, and sometimes from mine.

The other scent that has always stuck with him is that of cigarettes. It permeated every last item of his clothing and every square inch of his office, from the carpet to the smoke-gray curtains, including his black leather pouf into which we loved to throw ourselves. This smell that I abhor today was, as long as I lived with my parents, familiar enough not to displease me. I particularly remember a cedar wood ashtray, brought back from a trip to Morocco, which sat on his desk most of the time but also accompanied him to every room of the apartment as he moved around. The mixed fumes of ashes, cold tobacco and the wood itself intrigued me enough that I was regularly tempted to lift the upper part of the object in order to sniff its contents.

The smell of his cigarettes – which I almost always saw him rolling himself – also blended particularly well with those of the thick black vest made of wool loops and leather pieces that he constantly wore at home. It probably went well with the smells of his skin and his sweat, those intimate smells that never put us off in the people we love. The vest, now very worn, leaves the wardrobe less often, but I still stick my nose in it during my visits – and I’m sure my brother does the same! Not so long ago, the latter also reminded me of the way we had, to recognize his parked scooter among many others, of sniffing the inside of the blankets which keep the bikers’ legs warm and dry. It is thus by the nose that we formally identified the father’s vehicle!

The family cook – my mother was more spontaneously involved in baking – my father put and still puts a lot of energy and determination into preparing various meat dishes: pork crepinettes during holidays in Normandy, zucchini stuffed with sausage meat for my birthdays, but also, on certain occasions, long-simmered pot au feu, roasted lamb shoulder with garlic, or even dishes more typical of the regions of origin of his parents, like sauerkraut with Strasbourg sausage or fasírts, these Hungarian meatballs that his mother and grandmother prepared before him. Strangely nostalgic scents for the vegetarian that I have become! A priori less pleasant, the smell of burnt pan bottoms, which he periodically forgot on the fire despite his cooking skills, also summons the smiling memory of family weekends and my mother’s howls of exasperation in the face of so much distraction…

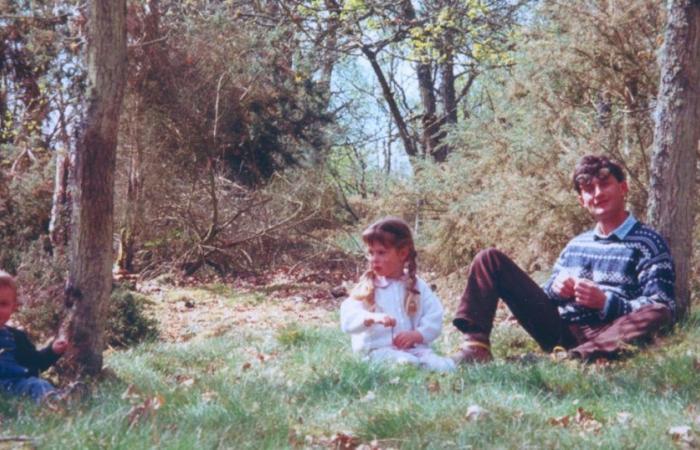

There are also all these scents which attach themselves to the happy memories of the adventures in which my father guided us: those, vivid, of Sunday walks in the forest, but also those of the bicycle room of the building on the departure and return of these walks; the damp, clayey smell of geosmin in the caves that we explored during each stay in the Lot or the Luberon; the smell of plastic from the lukewarm diving mask just after spitting in it to prevent fogging; the smells, both synthetic and mossy, of the tents deployed during bivouacs in the Alps; the warm, dusty scent of the canvas hammocks in which we took naps in the summer; the pungent exhalations of wood fires, lit indifferently in a fireplace or in the open air, and which clung to his black hair… All of this is also “the smell of my father”.

Perhaps it is because there is already so much wealth there that the idea never occurred to me to offer it a perfume. While over the years I have searched for each of my loved ones there fragrance that would suit them and exalt their being, this quest never manifested itself in the case of my father. Sometimes, everything is already so there, absolute of meaning and evidence, all the smells already so sedimented in memory and imagination, that a juice would have nothing more beautiful to tell. Like that ancient smell ofafter shave, I think a perfume could only steal my father’s scent. And I cannot allow that.

Main visual: © Laure-Emmanuelle Muller