Photo credit, Getty Images

- Author, Hugh Schofield

- Role, BBC News

- Reporting from Paris

-

15 minutes ago

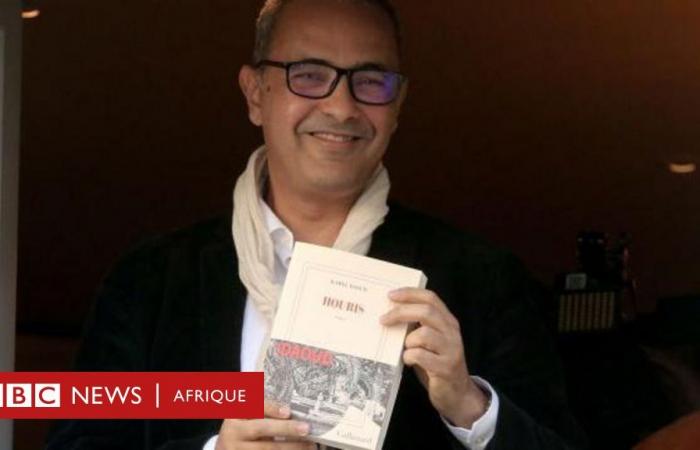

For the first time, an Algerian author has won France’s most prestigious literary prize, the Goncourt, with a searing account of his country’s 1990s civil war.

The novel Houris by Kamel Daoud recounts Algeria’s “black decade”, marked by blood, during which up to 200,000 people were killed in massacres attributed to Islamists or the army.

The heroine, Fajr (Dawn in Arabic), survived having her throat slit by Islamist fighters – she has a smile-shaped scar on her neck and needs a talking tube to communicate – and tells her story to the little girl that she carries inside her.

Written in French, the book “gives voice to the suffering of a dark period in Algeria, in particular to the suffering of women,” the Goncourt committee said.

“It shows how literature… can trace another path for memory, alongside historical narrative.”

The irony is that few Algerians are likely to read it. The book does not have an Algerian publisher; the French publisher Gallimard was excluded from the Algiers Book Fair, and the news of Daoud’s success with Goncourt has – a day later – still not been reported in the Algerian media.

Worse still, Mr. Daoud, who now lives in Paris, could even face criminal prosecution for speaking about the civil war.

A 2005 law on “reconciliation” considers “instrumentalizing the wounds of the national tragedy” a crime punishable by prison.

According to Mr. Daoud, this has the effect of making the civil war, which traumatized the entire country, a non-issue.

“My 14-year-old daughter didn’t believe me when I told her what had happened, because war is not taught in schools,” Mr. Daoud told the Le Monde newspaper.

“I cut out some of the worst scenes I had written. Not because they were false, but because people didn’t want to believe me.”

Mr. Daoud, aged 54, had direct experience of the massacres because he was a journalist at the time and worked for the Quotidien d’Oran. In interviews, he described the horrifying routine of counting bodies, then having his count altered – up or down – by authorities, depending on the message they wanted to send.

“You develop a routine,” he said. “You come back, you write your article, then you get drunk.

Photo credit, Getty Images

He worked as a columnist for many years, but gradually drew the wrath of the Algerian government due to his refusal to toe the line.

He strongly criticizes what he considers to be an official “instrumentalization” of the 1954-1962 war of independence against France, as well as what he considers to be the persistence of the subjugation of women in Algerian society.

“In a way, the Islamists lost the civil war militarily, but they won it politically,” he said.

“I hope my book makes people think about the price of freedom, especially for women. And in Algeria, he encourages people to confront the whole of our history, and not to fetishize part of it to the detriment of the rest.

Daoud has previously written two novels, one of which – the highly acclaimed Inquiry into Meursault – was a rewrite of Albert Camus’s The Stranger and was shortlisted for the Goncourt in 2015.

In 2020, the author moved to Paris, “exiled by force of circumstances”, and took French nationality. “All Algerians are Franco-Algerians,” he declared. “By hatred or by love.

In Algeria, he is a divisive character. His enemies consider him a traitor who sold his soul to France, while others recognize him as a literary genius of whom the country should be proud.

During the press conference following the award ceremony, Daoud himself declared that it was only by coming to France that he was able to write Houris.

“France gave me the freedom to write. It’s a haven for writers,” he said. “To write, you need three things. A table, a chair and a country. I have all three.