This masterpiece by filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, Jean Vigo Prize 1966, is very “new wave” – in terms of form, but has unfortunately lost none of its relevance at a time when modern slaves finally dare to bear witness to violence domestic and where xenophobes of all kinds are unleashed on social media….

Sandra Joxe

“I didn’t think we would have such proof of the need to show this film today. It’s a bit of the problem with all the films showing at the moment as soon as a subject addresses the question of immigration…” confides the film’s distributor, who received offensive messages as soon as the film’s new theatrical release was announced.

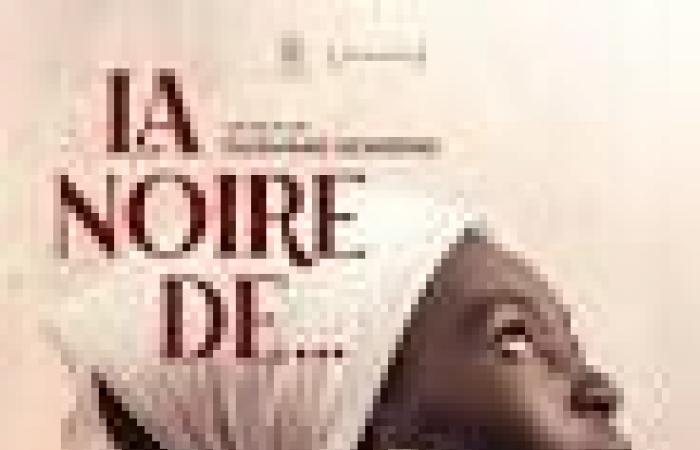

Indeed, The Black of… is not only a major cinematographic work revered by cinephiles but too little known by the general public, an artistic gesture of remarkable audacity and plastic beauty, illuminated by the beauty, the magnetic grace of its interpreter – Thérèse Mbissine Diop – it is also a cry of revolt which marks a date in the history of cinema.

An activist film

The Black of… is considered the first feature-length fiction film by a filmmaker from sub-Saharan Africa, directed by the novelist and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène (1923-2007). The film marked the end of the Laval decree taken in 1934, well before the Vichy regime, which prohibited Africans from making cinema (!).

Upon its release, the film was widely acclaimed, winning numerous awards at European and African festivals and establishing Sembene as the father of African cinema.

It is an adaptation of one of his short stories, itself inspired by a terrible news item, recounted in a laconic article published in Nice-Matin: “A young black woman slits her throat in her bosses’ bathroom“. This relentless story of self-dispossession and a rapid descent into hell brilliantly denounces the violence of relations of domination stemming from colonial history, modern slavery and ambient machismo.

“France is beautiful”

The first images of the film evoke the arrival in France, by liner, of an elegant and charming young Senegalese woman, with a lively and graceful silhouette: a true icon of the sixties, distant cousin of a Jean Seberg or an Anna Karina.

And here is Diouana, delicious dress and matching earrings, the heels of her pumps clicking on the cobblestones. A beautiful appearance. Her boss is waiting for her at the landing stage and the die is quickly cast: the young beauty has come to join her employers, a white family from Dakar recently settled in Antibes, to look after the children. “France is beautiful” says the boss laconically at the wheel of his Simca, thus punctuating the amazed look of his future “handywoman” whom he is bringing home. But of the dreamland, Diamo will see nothing at all.

Perpetually locked in the apartment, condemned to do all the household chores, isolated, humiliated by her cantankerous and frustrated boss… she sees all her dreams of freedom and emancipation disappear, she suffers real slavery.

Between revolt and despair…

The radiant creature of the first images withers visibly, her eyes fade, her body shrivels up, her reaction to the shameless exploitation of which she is the victim is a mixture of revolt and despair. We feel the strength of character of the character, in his gaze, in his gestures but also in his intimate considerations, relayed by a voice-over that is a true litany-lamento that is both poetic and political.

She initially refuses to submit and her resistance is manifested not only by her internal monologue but also in her relationship with her body: preferring to mop the floor in pumps than in slippers, she is lectured by her mistress. She has a hard time putting up with the ridiculous maid’s apron that she has to put on over her pretty dress, and even worse the greasy kiss from a guest delighted with her experience:“I had never kissed a black girl before” and the tears flow despite herself.

She tries to resist, but the balance of power is not in her favor, we know that well, she knows that well: she who only speaks Wolof.

All that remains is despair… here she is lost in her memories, so many flashbacks which reveal her appetite for life, her lost energy, grace and power of seduction and her last moments spent in the working-class suburb of Dakar. So many quasi-documentary “slices of life” and praised by Jan Rouch at the time of the film’s release.

When Diouana was recruited as a governess to look after Madame’s children, in one of these settler neighborhoods, she believed herself to belong to the cream of the elite. But here it is uprooted, as if imprisoned: it is withering, it is extinguished. In a final attempt at survival she recovers the superb mask that she had brought in her luggage and offered to her jailers, the symbol of her dignity. But it is too late, she is overcome by a deep and tragic depression and ends her life.

An unforgettable actress… but forgotten

The director entrusted the role of Diouna to Thérèse Mbissine Diop, a young seamstress whose hieratic beauty contrasts with the baseness of “Madame” and “Monsieur”.

The actress admirably juggles a whole series of emotions, always on edge with her skin and her eyes and reveals herself to be excellent in all areas: when she is still driven by the hope of a better life, her body (magnificent ) exudes sensuality, atomic energy and bursts the screen. But when she gives up the fight and collapses on her bed, overcome by melancholy, her gestures border on those of the best tragediennes.

There is a real choreography of feelings in his acting, which the director was able to capture thanks to a very fluid camera serving very composed frames.

The final suicide of her character but also a very beautiful one in which she undresses (nudity probably being her last refuge in the face of everything that is imposed on her) shocked spectators at the time of the film’s release, especially in Africa. . Her career as an actress did not have much success: she was labeled as a “communist” (Ousmane Sembene was indeed a communist and had studied cinema in Moscow) but, even more seriously, as a “whore” in her own right. country. Having returned to her activity as a seamstress despite a few appearances on the screen, at 75 she remains the unforgettable heroine of this moving film which resonates loud and clear with debates that could not be more current.

Cinematic modernity and topicality of the subject

Ranked among the 100 most important films of all time according to the annual ranking of Sight and Sound, the film was restored thanks to the Foundation of Martin Scorcese, a cinephile if ever there was one!

For the voice-over, sometimes political, sometimes poetic or both at the same time.

For the offbeat tone of the characters.

For shots of everyday objects, everyday gestures.

For the economy of filming resources, produced with a team of actors, most of them amateurs, set the tone for this work of exemplary sobriety and which, initially, was only to be a short film.

All the cinematographic biases (chosen or imposed by lack of means) give this unclassifiable film an original and disturbing character. “Originally planned as a short film, the film gained momentum thanks to the richness of the content filmed by a small crew. It was only during editing that the importance of the film became evident. specifies Alain Sembene, the director’s son. And to specify that, even if the character is a woman and her trajectory is a tragedy, there are undoubtedly autobiographical elements in this story: Ousmane Sembene himself arrived in France by liner (in Marseille) with a heart full of hope and in a very elegant outfit: suit and tie recovered from a family heirloom. And to add “it was his elegance that allowed him to go unnoticed during checks and not to be disembarked like many of his friends who were sent back to the country.”

A choreography in Black & White…

But it is the end of the film which is the most surprising and opens the narrative towards worrying horizons: the boss returns to Senegal to bring back the famous mask which symbolizes the identity of the young woman (we obviously think of Dahomeythe beautiful documentary on the restitution of Beninese treasures, which we recently chronicled which can be read below).

He crosses, he wanders in the suburbs of the city in search of the family of young Diouana and all eyes converge on him: the white man, the intruder who caused the death…

We expect retaliation, but no.

The violence remains deaf, in the looks, in the gestures, in the movement of bodies around him, of these black and anonymous bodies, united in disapproval, which follow him and observe him and glare at him… And these silhouettes worry the wandering protagonist, clumsy in his white body, who is a task.

Once again, little verbiage in this film, bodies that speak, looks that scream.

The Black of… is also a choreographic work, and that is not its least quality!

But the violence remains in suspense and is all the more threatening… relayed, even sublimated by the violence of the visual contrasts of this magnificent black and white film, which sometimes makes us so nostalgic for the cinema of the 60s…

Tribute to the wandering souls of the treasures of Benin