Comic book authors increasingly address sexual violence in their stories. And the question of their representation arises, which is fundamental in order not to offend the readership and the victims.

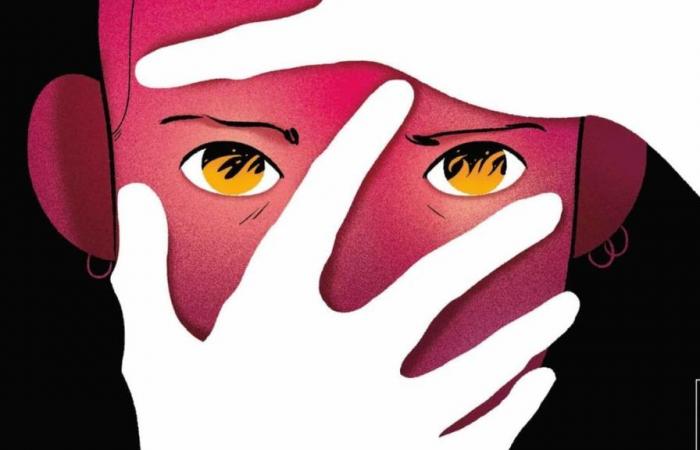

“For this society to change, we must have the courage to confront what rape really is.” These words, spoken at the Mazan rape trial by Me Stéphane Babonneau, Gisèle Pelicot’s lawyer, show the extent to which the representation of sexual violence has imposed itself in public debate in recent years.

Art, and particularly comics, actively participate in this discussion. Several albums released in September bear witness to this. Autobiographical stories Impenetrable by Alix Garin (Le Lombard) and Hatch by Aude Mermilliod (Casterman) thus retrace the journey of women who learn to reclaim their bodies and their desire after having been victims of sexual violence between childhood and early adulthood.

In the thriller The Lighthouse (Steinkis), Valentin Maréchal talks about sexual assault in the gay community. Screenwriter Lauriane Chapeau, for her part, addresses her attack by her teacher in Small big (Glénat). In November, Grégory Panacionne will finally explore this theme in Our forgotten souls (Le Lombard), according to a story by journalist Stéphane Allix.

He has already treated it in The Man in Black (Delcourt), an adaptation of a novel by Giovanni Di Gregorio published last May. These books have in common that they suggest more than show sexual violence. Shadow play, close-ups, ellipsis, slightly blurred scenes… All the language of comics is deployed to depict this long-taboo subject.

“Break the chain of silence”

“Everything that happens (in society) authorizes popular culture to take up this subject,” explains Aude Mermilliod to BFMTV. “I needed to create characters, situations to tell what had happened to me,” confirms Valentin Maréchal.

For her part, Lauriane Chapeau had “no need to make this comic to exorcise what happened to (her)”, but made it “out of commitment”. “We must break the chain of silence. My aim is also to expose National Education,” explains the screenwriter, who is also a school teacher.

The majority of these stories being autobiographical, it is often the memories which dictate the way in which these events will be represented. If Alix Garin briefly mentions in Impenetrable the attack to which she was the victim as a child is that the facts took place in this way. “It doesn’t go any further because it didn’t go any further. It’s not a desire to ellipse. Everything was represented from A to Z.”

“I wanted to give this scene the place it has in my life: a place that is not central,” insists the designer. “It’s part of my journey, not my identity. I wanted to approach it that way.”

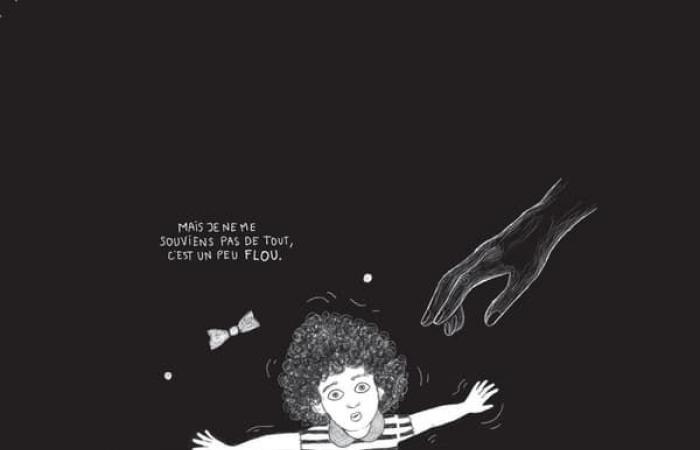

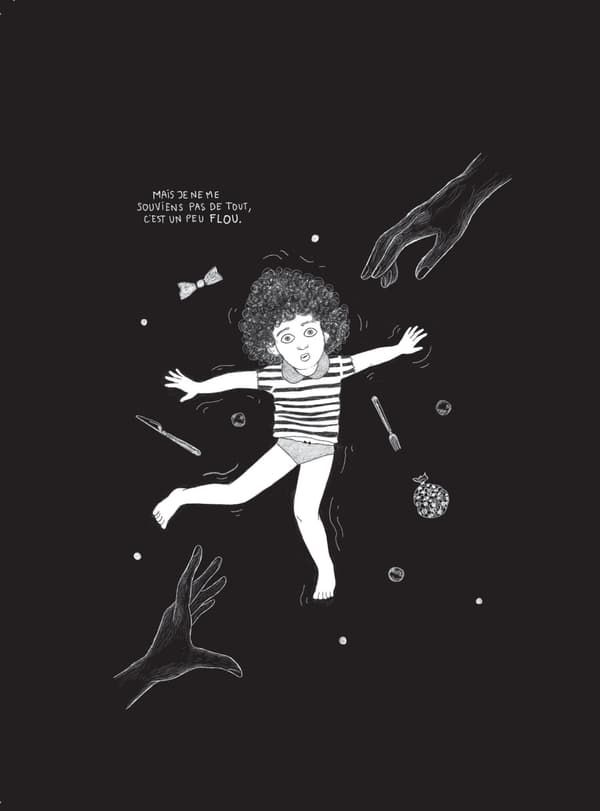

Show confusion

In Small bigthe aggression also remains off-camera because Lauriane Chapeau retains no memory of it. “I have traumatic amnesia. And even if I wanted to tell the story, I would rely on testimonies which were given at the trial and which are not mine. I do not have the authority to do so. And the subject is not the aggressor, nor this moment, but what comes after.”

Keeping the aggression off-camera also allows us to highlight the evolution of their understanding of the event. In Hatchthe rape scene thus returns several times, each time with new information. “What I wanted to show was the confusion that it created in the character not knowing if it was serious or not,” confirms Aude Mermilliod.

“When this kind of thing happens, we are not always immediately aware of what is happening,” adds Valentin Maréchal, who adopted a similar graphic approach in The Lighthouse. “There is a gap between the moment when it happens and the moment when we understand. In my case, I knew that I had experienced something difficult, but it took me six or seven years before I understood what happened to me.”

Don’t be too frontal

Showing sexual violence head-on can also offend the sensitivity of the readership. And bring the victims back into their own history. “I want the message to get across and to do that, we must not be too frontal,” says Lauriane Chapeau. “You have to find the crest line. Suggest, which is often very powerful narratively, without leaving the slightest doubt,” summarizes Alix Garin.

Valentin Maréchal also asked himself the question by drawing The Lighthouse. “Basically, the sequence of the attack was longer. It was a little harsher too. I talked about it with my editor and ultimately, I changed the way I wanted to draw the scene. It didn’t change. was not about doing something that was a punishment, like in the movie Irreversible (which features a long rape sequence in fixed shot, Editor’s note).”

“When you are sexually assaulted, it is so violent, so unspeakable, that we don’t want to show it or share it,” adds Lauriane Chapeau. This is why women also take so long to testify. We do not write to show this pure violence, but to demonstrate its impacts.”

Analysis shared by Alix Garin. “The real images, I have them all the time (in my head). I live with them. When I was in therapy, I made a lot of hand drawings of this event in completely confidential notebooks, which were not not intended to be seen.” Raw and “much too violent” drawings, “impossible to put in (one’s) comic book”.

Avoid voyeurism

Suggesting above all prevents any voyeurism. “I especially did not want to enter into the pitfall of the eroticization of rape,” agrees Valentin Maréchal, who on the contrary wanted to “show that consent can be sexy.” Aude Mermilliod also took care not to draw images that could become masturbatory supports.

“Showing sexuality with wide shots can awaken a sexual imagination that will remind us of pornography,” underlines the designer. “And I absolutely did not want it to be assimilated to sexuality. I wanted us to be in the representation of abuse. So I chose to show very little of the bodies together and to stick to its sensations to her, on what she experiences directly.”

“I especially wanted to protect the character and not myself as an adult,” she continues. “I didn’t want her body as a little girl, a young teenager, to be a tool that could be exciting for readers.”

Abstract approach

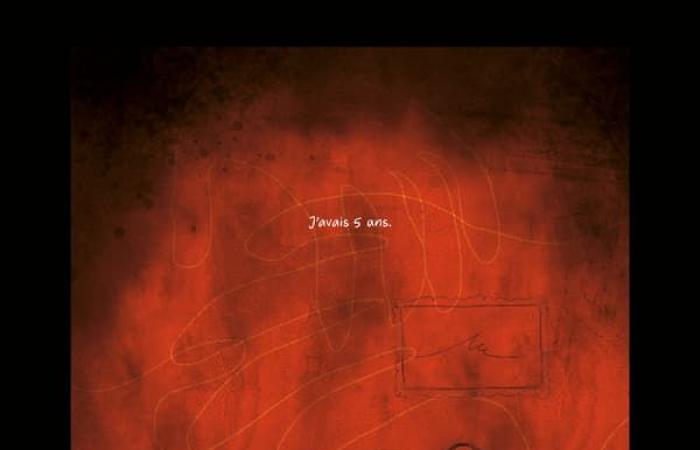

Finding the right graphic approach is also essential. To materialize the “oppressive, distressing dimension” of her aggression, Alix Garin favored “a more abstract approach”. “I wanted a slightly blurred effect, as if someone had tried to erase the pencil from a sheet of paper. A little dirty charcoal. Something a little soiled.”

Valentin Maréchal used more close-ups and off-camera shots. “I wanted to immerse myself in this absolutely unpleasant and disgusting feeling,” he says. “But it was complicated. I redrew this scene many times. If I had to talk about it again in another comic, I would talk about it in another way.”

Red also recurs frequently to represent these attacks. The color imposed itself on Alix Garin “by elimination”: “We needed a color which would have the effect of a slap and which would be aggressive to the eye.” “The red becomes sticky, a little pasty, a little heavy in the scenes which talk about abuse,” adds Aude Mermilliod.

The power of joy

Drawing these events is most often trying. “It wasn’t pleasant to spend hours drawing those pages,” concedes Aude Mermilliod. “But it didn’t make me sad. It was more like tension.” Valentin Maréchal was embraced by the same sensations. “It lasted several days. It wasn’t easy because it sent me towards rather unpleasant things. I tried to distance myself by listening to somewhat gentle music.”

A necessary distance, especially since these albums depict, beyond the attacks, much more joyful images of characters regaining a taste for life. “It’s like in real life,” exclaims Alix Garin. “I believe in the power of joy. Good memories can end up replacing bad ones. I find it important to offer optimistic representations in today’s world.”

“Art shapes the world we live in. I want to live in a world where people are more resilient, where they can learn and hear that there is a future,” concludes the designer. “We have the impression that to be heard in the seriousness of these facts, we have to show that we suffer in perpetuity. I would like that to no longer be the case.”