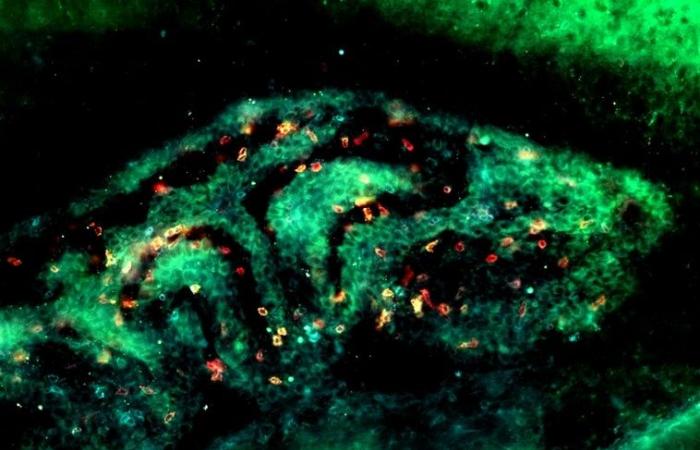

Marking of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8 in red and the “residence” marker CD103 in green) housed in the choroid plexus of a brain infected by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. © Amel Aïda

Toxoplasmosis is an infection caused by a parasite called Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii). In more than a third of the human population, this parasite establishes a chronic brain infection which can have serious consequences in people whose immunity is weakened. Better understanding the immune mechanisms that control this infection is essential to hope to develop new therapeutic strategies because to date, no treatment can eliminate the persistent form of the parasite. The study, carried out by Inserm researcher Nicolas Blanchard and his team at the Toulousain Institute of Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases (Infinity, University Toulouse III Paul Sabatier, CNRS, Inserm), showed that a category of immune cells, “resident” CD8+ T lymphocytes play a key role in detecting and neutralizing the toxoplasmosis parasite in the brain. These results published in review PNASallow us to consider new treatment options to eliminate persistent forms of toxoplasmosis.

Toxoplasmosis is a very common parasitic infection in humans. One in three people, or even one in two in some countries, has been exposed to this parasite during their lifetime. The parasite is transmitted by direct contact with the feces of a feline carrying the parasite T. gondiior by consuming contaminated foods (undercooked meat, raw fruits and vegetables).

The consequences of this infection vary depending on the individual. In healthy people, the consequences of this infection are most often not serious: the infection can cause fever and fatigue, but the symptoms often go unnoticed. However, the parasite is not eliminated from the body. It can persist for a long time in a so-called ‘latent’ form in the muscles, the retina and the brain. A growing body of data suggests that this chronic brain infection is associated with behavioral changes and even an acceleration of neurodegenerative phenomena. In addition, in a person whose immunity is more fragile, such as a person suffering from AIDS or using certain immunosuppressive treatments (for example in the case of a transplant), the consequences can be severe because the parasite can reactivate in the brain and cause potentially fatal brain inflammation (called cerebral toxoplasmosis or neurotoxoplasmosis).

To date, there is no treatment to eliminate the persistent form and permanently eliminate the parasite. Better understanding the immune mechanisms that control the parasite, particularly in the brain, could suggest new therapeutic strategies aimed at stimulating natural immunity to the parasite in order to better contain or even eliminate it.

The research team had previously shown that specific immune cells, called CD8+ T lymphocytes or “killer” T lymphocytes, play a key role in controlling the parasite in the brain. However, this is a very heterogeneous cell population. For Inserm researcher Nicolas Blanchard and his team, it was crucial to identify which subtype of CD8+ T lymphocyte is involved, to elucidate the immune surveillance mechanisms of the parasite in the brain.

In 2009, a particular subtype of CD8+ T cells called “resident” was discovered. These resident T lymphocytes have the particularity of not patrolling the body but remaining stationary in the tissues, particularly in the brain. The role of brain-resident CD8+ T lymphocyte subpopulations in the neutralization and elimination of the parasite had never been studied.

To study this role, the researchers relied on an animal model mimicking latent infection with T. gondii found in humans. Through the selective elimination of circulating subpopulations or resident subpopulations, the team showed that control of the parasite in the brain is ensured by resident CD8+ T lymphocytes, as opposed to other lymphocytes that patrol the tissues. and lymphoid organs.

Researchers have also shown that resident CD8+ T lymphocytes are formed thanks to signals sent by other immune cells, CD4+ T lymphocytes.

« This result caught our attention because it allows us to better understand why people carrying HIV are potentially more vulnerable to cerebral toxoplasmosis. Indeed, HIV is known to reduce the number of CD4+ T lymphocytes, which could have a negative cascade impact on the formation of resident CD8+ T lymphocytes in the brain, and therefore impair immunity to the toxoplasmosis parasite. “, explains Nicolas Blanchard.

Armed with these results, scientists will now be able to think about strategies to try to improve the capacity of resident lymphocytes to fight against brain infection.

“Now that we better understand the surveillance mechanisms of the toxoplasmosis parasite in the brain, we are carrying out further work to understand the mechanisms put in place by the parasite to escape the control of CD8+ T lymphocytes and how we can try to to neutralize these mechanisms”concludes Nicolas Blanchard.