ADAGP, Paris 2024 Private collection, Lisbon. View of the “Arte Povera” exhibition, Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, 2024 © Photo: Florent Michel / 11:45 a.m. / Pinault Collection

Joel Chevrier, Grenoble Alpes University (UGA)

Currently presented at the Bourse de Commerce/Collection Pinault, the “Arte Povera” exhibition traces the Italian birth, development and international heritage of this unique artistic movement. There you can discover more than 250 works by the main protagonists of Arte Povera. We visited it with Joël Chevrier, physicist, who is closely interested in the links between arts and sciences, and was particularly sensitive to this large-scale retrospective.

This is an immediately impressive exhibition, by the space in which it is displayed and the 250 works presented, but also by the nature of the works, most of them designed in Italy, in the heart of the thirty glorious years. We explicitly see the energy coming from fossils at work, an energy which transforms matter in a thousand ways. Energy, materials, transformations: the physicist is in his element!

At the birth of Arte Povera, young Italian artists

In 1967, when the art critic Germano Celant created this movement, naming it “Arte povera”, Michelangelo Pistoletto was 34 years old, Giovanni Anselmo, 33, Jannis Kounellis, 31, like Luciano Fabro. As a physicist, I realized during the visit that, although my discipline contributed to transforming the world during this period, it is not a reference here.

The proposals of these artists are anchored not in science but in their creativity, their own vision, against a backdrop of experimentation in the workshop. They go behind the curtain, showing the heart of the machine stripped of design. We think here of the opposition between contemporary visions, with on the one hand Raymond Loewy, the designer of the entire consumer society – already in 1893, the Chicago World’s Fair announced “Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Conforms”, “Science discovers, industry applies and man follows”) – and on the other hand the designer Victor Papanek who wrote in 1971 Design for the Real World, Human Ecology and Social Change(Design for a real world: human ecology and social change).

Working outside the scientific and technical conceptual framework at work everywhere around them, they seize it in order to better turn away from it. Everything goes: the materials, the devices, the thermal machines that found the XXe century (thermal power plants, cars, planes, etc.). By laying bare, they show us the world as it is and as it will be defined, more and more industrial, more and more energy-intensive. A formidable lucidity and relevance.

Joël Chevrier discovers Pino Pascali’s installation, “Confluenze” (1967).

Gabriel Robert/The Conversation France

Iconic works

Michelangelo Pistoletto’s “Mirror Paintings” are above all plates of stainless steel. Pistoletto had also tested aluminum: steel and aluminum are two flagship materials of the thermo-industrial society, and which require – an apparent paradox for a “poor art” – a very high scientific and technological mastery as well as a large quantity of energy to be produced. Michelangelo Pistoletto invites us to look at ourselves in the face in the material which, at that moment, changed the world, in the era of triumphant steelmaking. What a disaster!

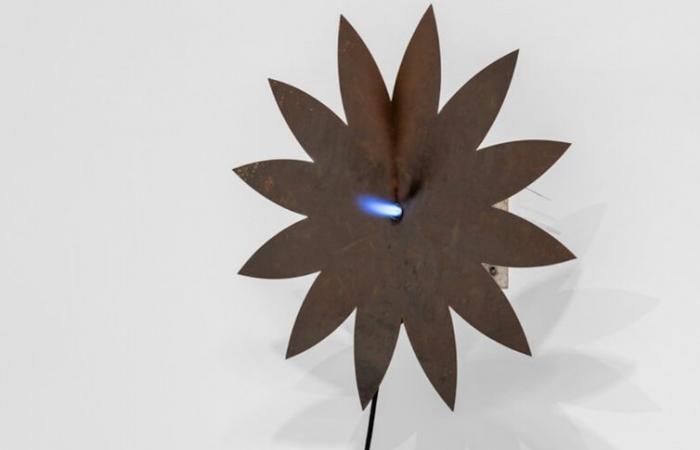

Jannis Kounelis burns gas through a nozzle in a raw steel flower. The gas forms a small blue flare, producing a characteristic noise. The gas cylinder is clearly visible. It is a very clean, very controlled fire, one which will allow high temperatures to be reached, and therefore to produce the movement and transformations of matter.

Jannis Kounellis, Sans titre (Fire Daisy), 1967.

Nicolas Brasseur/Pinault Collection

But let’s stop for a moment Lead II (1968) by Gilberto Zorio. The exhibition label says it best:

“_Two sheets of lead, copper sulfate, hydrochloric acid, fluorescein, copper braid, rope.

The work, designed like an electric battery, transforms chemical energy into electricity. On the ground, Gilberto Zorio places two lead containers attached to the wall by a rope, and pours into one of them a mixture of copper sulfates and water, which turns blue, into the other a mixture hydrochloric acid and water, which turns green. A braided leather thread is stretched between the two containers, immersed at each end in one of the two liquids. When brought into prolonged contact with the two substances, the copper becomes covered with crystals, while the coloring of the two liquids demonstrates the transmission of energy from one to the other. The artist uses industrial materials to create an energetic process that evokes an alchemical experience._ »

The work is rustic, it looks like a poorly constructed laboratory setup. We are placed at the heart of the device, as if the artist were lifting the hood. And with this work, the detailed review of the key elements of the industry of the 20the century continues: here electrochemistry and electrometallurgy.

Other notable works are the thermal machines by the same Gilberto Zorio. What a shock to see them like this! They line the entire exhibition, from the entrance, then in the rotunda. We also see them in a room dedicated to them (the “Casa ideale”), and in which we feel the cold! The motors and heat exchangers are exposed, they are part of the work. We see them wasting energy live, trying to cool the world. Like these air conditioners in stores that are wide open to the outside… Here, the cooling is such that frost forms on lead structures, like in a refrigerator where the door is left open. Having seen the exhibition on its opening day, I don’t know if the aim is to let the frost accumulate in an ever thicker layer.

I am thinking here of the unique and major work of Sadi Carnot, Reflections on the driving power of fire and on the machines capable of developing this power :

“If one day the improvements in the fire machine extend far enough to make it inexpensive in establishment and fuel, it will bring together all the desirable qualities, and will cause the industrial arts to take on a development of which it would be difficult to foresee the whole ‘extent. Not only, in fact, does a powerful and convenient motor, which can be obtained or transported anywhere, replace the motors already in use, but it causes the arts where it is applied to take on a rapid extension, it can even create entirely new arts. »

Carnot was visionary in formulating this in 1824. But so was Gilberto Zorio, who like his comrades had taken stock of the subject, and continues to confront us with the effects of thermo-industrial civilization.

The artist JR asks again today: “can art change the world? » Arte Povera, from the 1960s, forcefully underlined that art could show how the world was experiencing a transformation of unprecedented magnitude. This group of artists had identified all the elements: massive mobilization of energy, profusion of materials used and constantly expanding industrial transformations. They made works without artifice, “poor” in this sense, stripped of the layer of design then made to make everything functional but also desirable. Here, the fridges are bare, without the metal covering of the legendary American Coldspot refrigerator created by Raymond Loewy and symbol of the “American way of life”. If we think back to advertisements or contemporary American films of Arte Povera, the contrast is brutal.

Materials, materials everywhere

The artists of Arte Povera have explored everything, or almost. With Venus of ragsVenus of rags, Michelangelo Pistoletto displays a mountain of fabrics and clothes piled up in front of a statue of Venus. Today, we know: fabrics, clothing and fashion represent a global industry that is very resource-intensive and generates enormous pollution.

Venus with Rags, Michelangelo Pistoletto, 1967.

Florent Michel/Pinault Collection

Further on, Jannis Kounelis displays a pile of coal. But other artists use the materials: we see leather, stone, prefabricated cement, water of course, more fabrics, woven copper wires, etc. Finally, there are the works of Giovanni Anselmo, in a room that astonishes the physicist that I am: our smartphones carry sensors that precisely measure orientation in space, vertical line and gravity, horizontal plane and rotation in space . The artist, through a singular path that I can’t even imagine, inscribes this evidence through installations and sculptures of moving elegance and simplicity.

Giuseppe Penone, another world?

I discovered Arte Povera long after I became acquainted with the work of Giuseppe Penone. For a long time now, he has taken my breath away (which he actually sculpted). Here, its metal tree loaded with heavy stones, in front of the Bourse de Commerce, opens the ball.

View of the square in front of the Bourse de Commerce.

Romain Laprade/Pinault Collection

Explore gravity, place yourself beyond categories, including the inert and the living, from hybridizations of materials, question durations with these abnormally twin stones and grains of sand, and then bring back the young tree in a wooden beam… I have already written about some of his works, always as a physicist, which is in no way a reference for him. I collaborated with him on the work Be windand sculpted for him the grains of sand exposed here. In Arte Povera, he has dug a singular furrow, which seems to me to open other horizons and ask other questions.![]()

Joël Chevrier, University Professor / Physics, Grenoble Alpes University (UGA)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.