When I was in the hospital, unable to move after a 10m return to the ground and in the dark about the fractures in my spine, strangely neither depressed nor angry. A little out of personal philosophy, and a lot because I clung to these amputees that I had seen at the 2012 World Championships, then 2016. In the memory of this young woman in a wheelchair, too, who warmed up by campusing my projects block. In short, I knew that climbing was not just reserved for “able-bodied” people, and that as far as I went in surpassing myself, disabled people were already waiting for me.

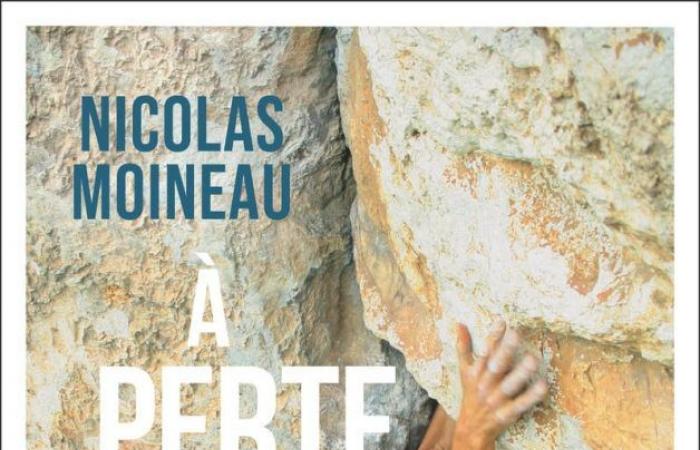

Discovering that a blind man had just scored, at the top, a 7c+, then last year an 8a, constituted for me a new source of incredulous wonder. This blind man is Nicolas Moineau, whose autobiography “Out of sight” is to be put between all the quickdraws.

It’s about climbing, of course. After all, it’s to her that he owes his taste for living again. It is thanks to her that he became world champion in 2012. And through her he astonishes all the needy clairvoyants whose 8a will always remain a blinding dream. We measure in Nicolas’ words what she represents for him, what he finds there, we learn by what path he met her and how she has informed his life.

But Out of sight turns out to be much more interesting than “just” that. The book answers a question you may never have asked yourself: what’s it like to live blind? Not only in the street, at home, the clashes and other ailments, but in practice every day, in encounters with clairvoyants, their clumsiness—most often out of ignorance and unnecessary embarrassment; in the development of public space, botched or forgotten inclusion policies, or the stressful headache of construction trucks during work or the silence of electric vehicles. Out of sight puts us face to face with our reactions and our achievements, makes us think about what we have and what it is like for those who do not L’don’t have.

We also learn a lot, in very accurate language, about the famous guide dog, how it is obtained, by what means and with what intensity the relationship is established, what bond unites the animal and man. Fascinating part.

The book is far from being miserable: Nicolas Moineau never laments his fate. He did it, as a teenager, in rebellion against the degeneration of his eyesight, the discomfort of his parents, the future. Pen in hand, he handles objectified pathos as well as self-criticism, the stick as well as light derision, self- and otherwise, using in particular puns almost all revolving around the meaning of view and its semantic field. In short, an unusual read for a life that we don’t usually imagine, a pleasure to read And instructive. In short, Nicolas Moineau does not see, and in doing so he allows us to see.

Text: Denis Lejeune

Photo from Mountains

When I was in hospital, unable to move after a 10m groundfall and in the dark about the fractures in my spine, I was strangely neither depressed nor angry. A bit out of personal philosophy, and a lot because I was hanging on to the amputees I had seen at the 2012 and then 2016 World Championships. The memory of this young woman in a wheelchair, too, warming up by campusing my bouldering projects. In short, I knew that climbing wasn’t just for the ‘able-bodied’, and that no matter how far I pushed myself, there were already disabled people waiting for me there.

Discovering that a blind man had just climbed a 7c+ on lead, then 8a last year, was a new source of incredulous wonder for me. This blind man is Nicolas Moineau, whose autobiography “Out of sight” is a must-read.

It’s about climbing, of course. After all, it’s partly thanks to our passion that he managed to regain a taste for life. It’s thanks to climbing that he became world champion in 2012. And thanks to it that he amazes all the hard-working fully sighted people for whom 8a will always remain a blinding dream. Nicolas’ words tell us what it means to him, what he finds in it, how he met climbing and how, to what extent climbing shaped his life.

Aim Out of sight turns out to be much more interesting than ‘just’ that. The book answers a question you may never have asked yourself: what’s it like to live blind? Not just in the street, at home, the bumps and bruises, but in everyday encounters with seen people, their clumsiness – more often than not out of ignorance and needless embarrassment; in the planning of public space, in botched or forgotten inclusion policies, or in the stressful headache of construction lorries during works or the silence of electric vehicles. Out of sight confronts us with our own reactions and what we take for granted, and makes us think about what we have and what happens to those who don’t.

We also learn a great deal, in very delicate and pointed language, about the famous guide dog, how it is obtained, by what means and with what intensity the relationship is established, what link unites the animal and man. A fascinating chapter.

The book is far from steeped in self-misery: Nicolas Moineau never laments his fate. He did so a teenager, in rebellion against the degeneration of his vision, his parents’ malaise and the future. With pen in hand, he wields both objectified pathos and self-criticism, the stick and light-hearted derision, self-mockery and the like, with the help in particular of puns revolving almost entirely around the sense of sight and its semantic field. In short, an unusual read for a life we don’t usually picture, a delightful and instructive read. In short, Nicolas Moineau doesn’t see, and in doing so makes us see.

Review by Denis Lejeune

Picture by Montagnes