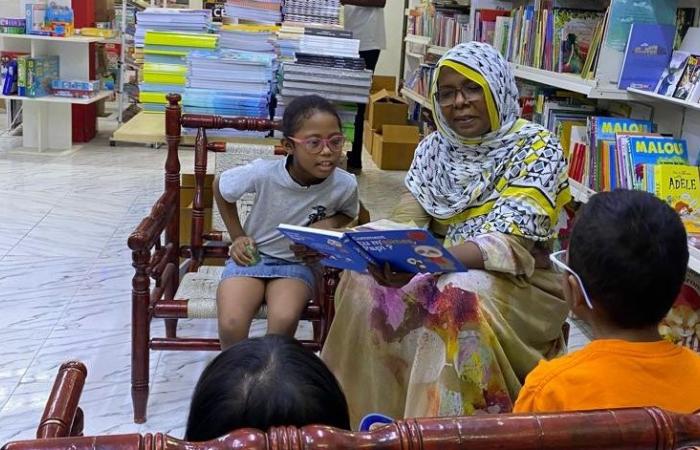

Arafo Saleh is a beautiful person whom I have known and admired for a long time. Our complicity as booksellers, our mutual support, our desire to move forward brings us closer together. She founded the two Victor Hugo bookstores, the Editions du Francolin and co-founded in Djibouti, the Association La Caravane du Livre. She is joyful, human, visionary and deeply open.

Agnès Debiage:What is the book situation in Djibouti?

Arafo Saleh: It is rather evolving in a positive direction since last April, we had a Book Fair, which was a great first. This allowed the book to step outside its traditional framework. For around twenty years, great efforts have been made to reach out to the public. We widely present to all audiences the works that we sell, but also those that we publish. For 3 years, I have also created Les éditions du Francolin.

On the national territory, there are three large libraries which have existed for 5 years and a few small libraries or reading corners in youth centers. A media library has even opened in Balbala. The French Institute also played an essential role even if the media library seems to be losing momentum.

What motivated your professional development by experimenting with different professions?

Arafo Saleh: I started out as a bookstore owner, because at the time there were several good bookstores in Djibouti, but none offered books at low prices. For a whole segment of the population, I represented an alternative to the new book. It was a general bookstore, but only offered second-hand books. This first bookstore made it possible to democratize books and it was important for me to have this action in my country, especially since we were emerging from a civil war and the situation was very difficult for many Djiboutians.

Shortly after, the Djiboutian state chose to create a Djiboutian school program with locally designed textbooks, abandoning the French program and imported textbooks. This sounded the death knell for certain bookstores which lived essentially on these sales of school textbooks imported from France.

This encouraged me to reposition myself as a bookseller, but putting Djiboutian school books at the heart of my activity. At the same time, I started importing titles which proved to be complementary. While the existing bookstores closed one after the other, I developed my business and in fact benefited from a clientele in demand for books. Here again, it is the context which guided my choice.

Over the past 3 years, I have noticed that more and more people are writing. Often these authors send their manuscripts to France, many are refused, but these texts speak about our culture and our environment. Based on this observation and in the absence of a Djiboutian publishing house, I said to myself that we had to create one to carry all these voices and introduce these texts which form our literary heritage.

It was a challenge, because in my context, there is no financial support. I had to create a reading committee, a correction committee and I had to train myself in this new profession. As always, I seized the opportunity by responding to the needs of the market.

Today, what do Djiboutians want to read? What types of books are their requests for?

Arafo Saleh: Oh big question! In the bookstore, today I sell a lot (to my great surprise) of titles recommended on TikTok, series that are very popular among young people and which circulate a lot on social networks.

Some influencers also make a natural link between the books they promote and the Victor Hugo bookstore. On certain series, I managed to sell 50 copies of a title in the space of a month to young people who had never set foot in the bookstore. These titles are marketed as pre-orders to a public that we absolutely did not know. The Djiboutian elite will turn more towards the human sciences, political news and literature.

Even if these readers are not very numerous, they are quite loyal. Young adults are very interested in books on personal development, a trend that is skyrocketing among us. And of course, the youth section remains a safe bet.

As an editor, I had a nice surprise this year: six schools adopted 70% of my children’s titles in their reading choices. It’s a source of great pride for me, because I didn’t think that they would penetrate the school environment so quickly.

During the Book Fair, I realized that there was a real readership for the books that I was publishing. And the parents were delighted to discover and choose these works. Other great prospects naturally open up, because I think that my titles once again meet market expectations.

You founded the Caravane du Livre association in Djibouti, what actions have you taken and their impact?

Arafo Saleh: This independent association under Djiboutian law was founded by a group of women readers, including the current Minister of Culture. We started from the observation that there were no cultural events around books and that we needed to make part of the population aware of the importance of books and reading.

What motivated us was to share moments with young people, particularly young girls who had dropped out of school and were kept away from books due to lack of means. We aim to bring the book to these young people, organize reading, poetry and slam competitions, but also include parents in our events.

For example, we organized reading sessions in unusual places such as the market. It was great to see housewives stopping, listening, discussing… We also chose to tell the books in local languages to promote accessibility. They were shown bilingual books to which they had access in their mother tongue and their school children could read at the same time in the language of instruction.

We were supported by our Ministry of Culture, the European Union, Unicef and the French Embassy, which gave us the opportunity to implement lots of great actions as part of this Book Caravan. Djibouti. This aid also allowed us to lower book prices by around 50 to 60% and even make book donations to certain populations. We continue these actions as long as possible.

In terms of the bookstore, how have you adapted? Why did you create a second bookstore?

Arafo Saleh: My first bookstore is in the heart of the business district, but it has become very difficult to access, crowded and with parking problems. As a result, our usual customers are no longer inclined to make this trip. On the other hand, when I decided with my son to open a second bookstore (more geared towards young people, comics, manga, etc.), we moved closer to schools and residential areas. The neighborhood where we have settled is in the making with high value-added real estate and cultural projects.

For the layout, I redesigned my premises differently, because my clientele differs and here too I adapted to their expectations, both in terms of furniture, circulation spaces, and classification. This bookstore is smaller than the other, but the books are better presented there. These choices were imposed on us. On the entertainment side, we have a kamishibai that we regularly use to run small youth workshops. This kamishibai allows us to vary the texts offered, adapted to a very young audience, but also to adolescents.

Do you feel supported by institutions in Djibouti and elsewhere, as a pillar of Djibouti books?

Arafo Saleh: Yes, definitely. Thanks to the Educational Resources program, I was able to benefit from essential training in Abidjan which I continue through individualized support, and this gives me new skills that I needed. This training also allowed me to interact with other African publishers, which is essential for me, and even to set up collaborations through rights purchases.

The French Institute of Djibouti is also a regular partner, as is the Ministry of Culture of Djibouti.

The programs of the Booksellers conference et Publishers conference in Sharjah were a first immersion into a professional world that I did not know. I was able to professionalize myself in the field of rights, all our rich exchanges within the delegation, the preparation of meetings, the support we received were decisive in evolving and capitalizing on opportunities.

And I published my first purchased rights titles last year in Sharjah. On the bookstore side, by meeting Arabic-speaking booksellers, I was able to win a call for tenders for books in Arabic in Djibouti. These two events really opened up lots of new doors for me that I never imagined!

Today what would you like to build with professionals from this part of Africa?

Arafo Saleh: The country with which we have a border, Somalia and more precisely Somaliland, where I have already been invited to the Book Fair, are for me a natural partner for the years to come. Arabic-speaking countries also interest me, because we share this language and Djibouti is part of the Arab League. Translations of works could circulate between us.

Kenya and Ethiopia are also countries that should offer opportunities for collaboration. The first publishes a lot in English and the second in Amharic. Kenya is very good at academic and extracurricular publishing, and I have already met some publishers in Sharjah.

What would be your dream for 5 years?

Arafo Saleh: It would be a coffee bookstore, I don’t know if I’ll be able to make it happen. But a cozy space that combines books and pastries, my other passion. With a real reading corner for children. And who would have a small truck that could travel through the villages of Djibouti.

It would truly be the culmination of a big dream. And for publishing, I would like to be able to switch to audiobooks, favoring local languages in addition to French. I am very motivated to open new paths as I have always done.

Photo credits © Arafo Saleh