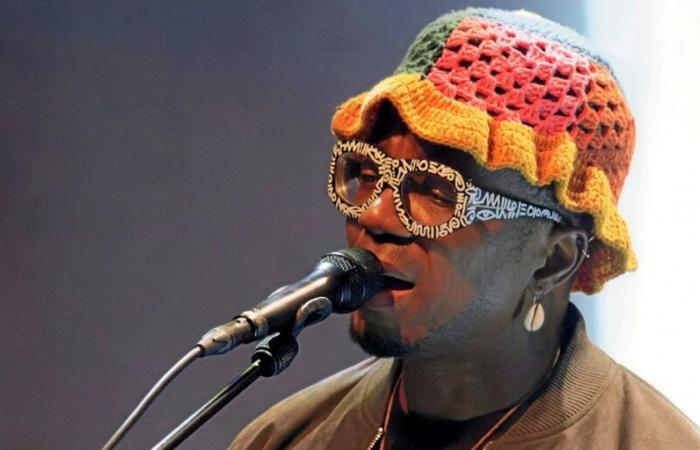

Dince its beginnings, Blick Bassy has brilliantly merged African traditions and modern influences. Shared between Cameroon and France, he returns with a deluxe version of his fifth studio album Madiba Ni Mbondian ecological and committed story centered on water, a resource that is both precious and at the heart of multiple conflicts, particularly in Africa.

Beyond his musical career, the artist-composer plays a key role in the “Memory Commission”, launched by French President Emmanuel Macron in 2022 to explore the role of France during and after the colonization of Cameroon. This dark past, marked by decades of colonial rule and the violent repression of the nationalists of the Union of Cameroon Populations (UPC), remains a taboo in Cameroon, despite the assassination of figures like Ruben Um Nyobè. Co-directed with historian Karine Ramondy, the commission has just submitted its report to the head of state. Before its official publication, it will be transmitted to the Cameroonian authorities.

Africa Point: Why did you agree to be part of this commission and what was your role?

Blick Bassy : My mission was to travel across Cameroon to collect testimonies, particularly those of the last living witnesses, and to cross-reference them with the archives in collaboration with a team of historians. This work aims to enrich the documentation on this colonial past while finally offering a voice to those who had never had the opportunity to be heard.

Beyond the final report, my goal has always been to transmit this memory through various documentary media, films and sound recordings, so that new generations can reclaim their history and participate in the development of a national narrative.

How did you respond to those who may have questioned your legitimacy in this role?

Initially, there were a lot of reactions, often due to a misunderstanding of our approach. Some people wondered about the presence of artists in this project. I then explained that culture plays a central role in our emancipation and our memory, like the griots, who are true guardians of our memories. Once people understood that our mission was to seek the truth by giving voice to first-hand witnesses, they understood the importance of our work. This project complements and enriches that of historians, and unlike other commissions, such as those on Rwanda or Algeria, which mainly involved historians, we have adopted a more inclusive approach. This allowed us to collect more diverse and rich materials.

France must understand that African people aspire to models of governance that respect their realities and traditions, without external interference.

Why does this story still remain a taboo in Cameroon and how has this process of collecting testimonies made it possible to break this silence, particularly with regard to the most vulnerable witnesses?

We should have undertaken this work of memory a long time ago in Cameroon, by and for the Cameroonians. This story remains vague, even for us, it has always been told by others. It is painful today, because many witnesses have disappeared. For example, one of Ruben Um Nyobè's widows has died in the meantime. Fortunately, we were able to interview him before his disappearance. Many elderly people were in the same situation, which pushed us to speed up the process to collect testimonies from the most vulnerable, particularly those who were seriously ill or very elderly. We traveled throughout Cameroon, including the north, where many UPC refugees had taken refuge, as well as the English-speaking area, in order to understand how these populations had experienced these events.

In a context of tense Franco-African relations and rising anti-French sentiment, do you think your report will really be taken into account? How did you carry out this work in such a climate?

The tense context of Franco-African relations should not obscure the fact that self-determination movements in Africa offer an opportunity to reinvent more balanced relations. France must understand that African people aspire to models of governance that respect their realities and traditions, without external interference. The emancipation of people requires recognition of their right to choose their own model of governance, without being subject to imposed models. Although this process may result in coups and other crises, these events are an integral part of the path to freedom and self-rule. If France really wishes to put an end to Françafrique, it must support this dynamic of autonomy and local governance.

Cultural and creative industries can become a key lever for the emancipation of African populations

Anti-French sentiment often comes from mutual incomprehension. Although these crises, including coups, may seem extreme, they reflect an inevitable process of struggle for independence and freedom. The right of people to govern themselves must be accepted. If Africans do not ask France to impose a model, the same goes for the French. It is time to rethink this relationship and build a common future, based on respect and autonomy of peoples, while recognizing that coups and other forms of protest are stages in the process of transformation and reconciliation. .

-How can the cultural and creative industries, now recognized by institutions such as the OECD as a key sector of development in Africa, sustainably transform local economies while promoting the continent's cultural identities?

For a while now, I have been interested in how the cultural and creative industries can become a key lever for the emancipation of African populations. By integrating the economic dimension of Art, we offer communities the means to adapt to the challenges of today's world, while asserting their identity and promoting their traditions.

Art has a unique power to touch hearts and transmit profound messages, but its impact depends on the structuring of this sector. It is imperative to develop infrastructure, finance training and support local innovators, who are often creative despite precarious contexts. By telling stories rooted in African realities, such as those of young people who are rediscovering and investing in their villages, we can transform traditional stories into drivers of action.

Cinema, for example, can play a central role in inspiring populations to see their territory as a wealth to be preserved and developed. These stories, financed and designed in a structured way, make it possible to escape from the paradigms inherited from colonization and to redefine the notions of wealth and success from a local perspective. Thus, cultural industries are not content with being a space of expression: they become a real tool for economic and social transformation.

Recreating a healthy relationship with life is the key to putting an end to these systems of exploitation and destruction

Your latest album Madiba Ni Mbondi puts water at the center, while continuing a reflection on colonial history and human imbalances. How do you perceive the link between the destruction of ecosystems and systems of oppression and how does your Music contribute to carrying this message?

Devoting an album to water does not mean turning the page on colonial history, but rather deepening this reflection. My project is based on the idea that human imbalances, such as colonization or imperialism, arise when we leave our natural role in the chain of life. Recreating a healthy relationship with life is the key to putting an end to these systems of exploitation and destruction. Only by recognizing the interdependence between all living things can we build a harmonious and equitable future, both locally and globally.

How did you manage to free yourself from dominant African musical trends?

To Discover

Kangaroo of the day

Answer

This album is an invitation to step outside the usual framework and explore sounds in harmony with life. Water embodies the idea of a balance to be found between humans and nature. Music, in this project, becomes a powerful vector to offer an alternative vision and awaken a collective consciousness, far from dominant patterns.