The damage caused by Cyclone Chido in Mayotte highlights the vulnerability of many homes in this small, very poor French archipelago in the Indian Ocean, where around a third of the population lives in precarious housing, which has been completely destroyed. .

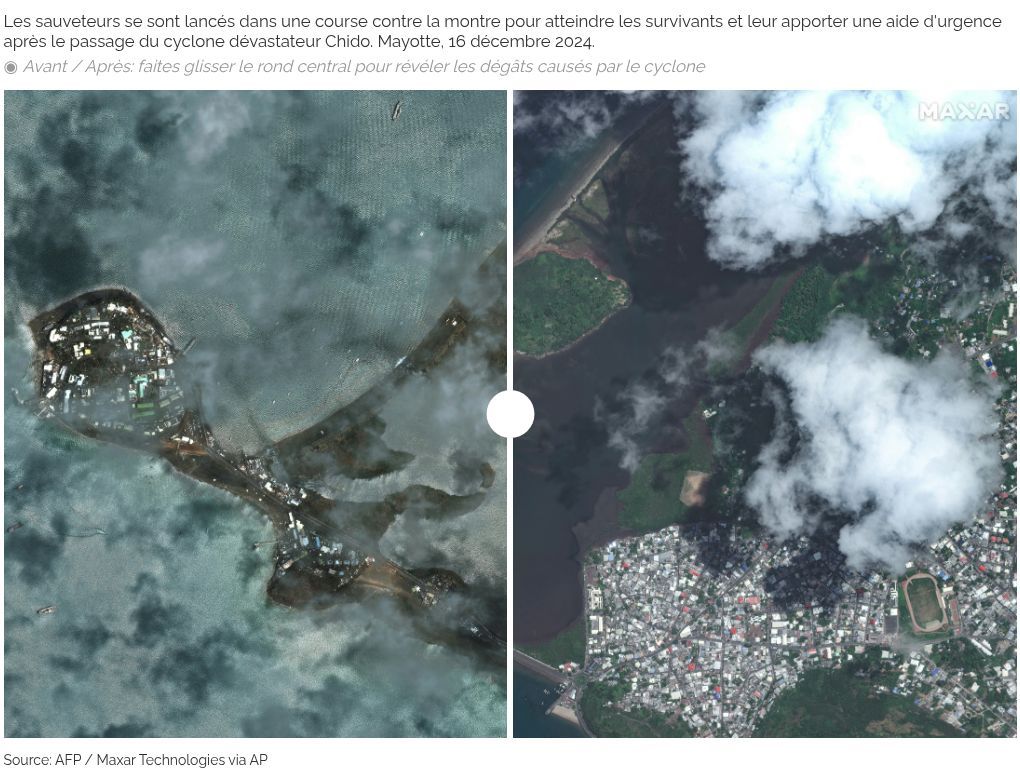

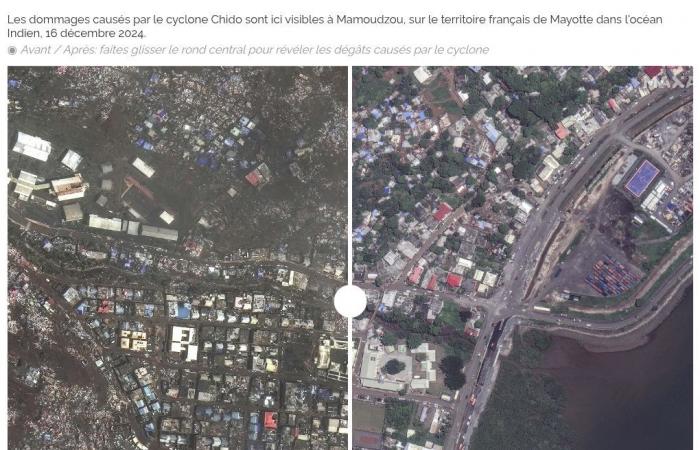

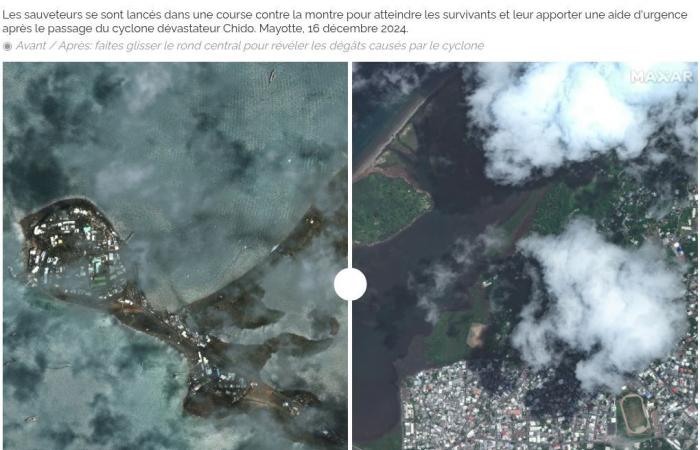

Satellite images published by the American company Maxar Technologies show the scale of the disaster. “All the shantytowns are lying flat, which suggests a considerable number of victims,” a source close to the French authorities commented on Monday, who fear “several hundred” deaths, perhaps “a few thousand.”

According to the most recent data from the French National Institute of Statistics and Studies (which dates from 2017), four out of ten homes are made of sheet metal in Mayotte, and three out of ten do not have running water. “It’s wood, sheet metal on dirt hills. You imagine the wind rushing in plus the rain creating mudslides,” says the director of emergencies and operations of the French Red Cross, Florent Vallée.

These precarious dwellings are not new to Mayotte. “Until the end of the 1970s, the majority of housing was built with plant materials,” recalls Mégane Aussedat, doctoral student in sociology and author of several works on Mahorais informal neighborhoods.

But despite the policy of reducing precarious housing put in place during this period, “access to land is difficult,” she assures. On the one hand, the number of available housing units has remained too low to cope with the demographic growth of the archipelago and the various migratory flows affecting it. And they remain “extremely expensive” for a population whose median income was 260 euros per month in 2018.

Since 2018, a law allows the prefects of Mayotte and Guyana to order the demolition of neighborhoods with precarious housing, provided they offer an accommodation solution, even temporary.

On the health front, the situation was already complex, in particular because of difficulties in accessing water: in the spring of 2024, a cholera epidemic which had spread to several shanty towns had left seven dead. Jean-François Corty, president of the NGO Médecins du Monde, fears a resurgence of this type of epidemic because of “chronic complicated access to water” after the passage of the cyclone.