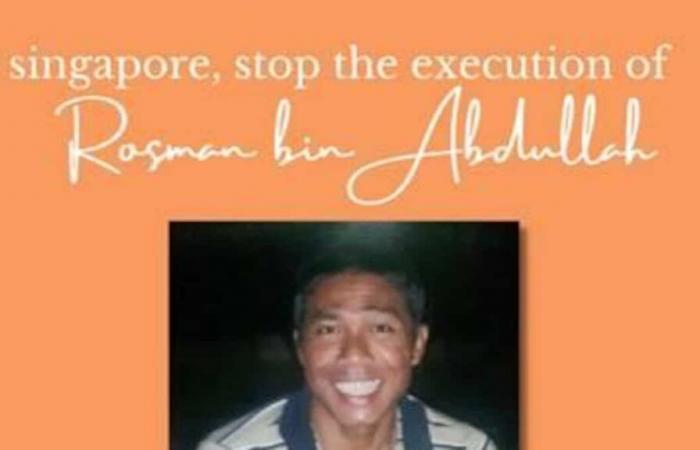

Despite calls for clemency from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Singapore last week hanged a drug trafficker. Rosman bin Abdullah, 55, was executed for trafficking 57 grams of heroin.

Under the city-state’s laws, anyone trafficking more than 15 grams of heroin or 500 grams of cannabis faces the death penalty.

Since executions resumed in March 2022, following a hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Singaporean authorities have carried out 24 executions, including eight so far this year. Last year, 11 drug traffickers were hanged. Of the 54 currently awaiting execution, all but three were convicted of drug trafficking offenses.

A modern city-state and international business hub, Singapore – along with Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Iran and China – is among the few countries that impose the death penalty for drug offenses.

The results of the death penalty

Illicit drug use is a growing problem globally. The estimated number of drug users increased from 240 million in 2011 to 296 million in 2021.

Singapore has one of the lowest drug addiction rates in the world: 30 addicts per 100,000 people, compared to 600 in the United States. The lifetime and past 12-month prevalence of illicit drug use in Singapore is 2.3% and 0.7%, much lower than in most developed countries.

Drug addicts undergo severe compulsory rehabilitation programs there. When they leave rehabilitation centers, the State ensures their reintegration into society.

Donald Trump, when he was president in 2018, expressed interest in Singapore’s policy of executing drug traffickers, saying it could help solve the opioid crisis. Will he act now that he is back in power?

What about Canadians?

Even if there is no question of drug trafficking, according to a recent poll, a majority would support the return of capital punishment in Canada, starting at 52% in Quebec and reaching 62% in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Conservative voters would be in favor at 69%, Liberals at 56% and New Democrats at 49%.

Canadians would favor the return of the death penalty, among other things, as a punishment adapted to the seriousness of the crime, and because it would also save taxpayers’ money, including the costs linked to keeping the guilty in prison for many years.