Their names are Zarin or Ayesha, they are 20 years old and were sold by their family as sex slaves for a few thousand euros. Even when severely repressed by law, the trafficking of young women remains a scourge in India.

In 2022, the Ministry of the Interior officially recorded 2,250 victims of human trafficking. The police officers responsible for repressing them arrested 5,864 suspects and the courts handed down 204 convictions for these crimes.

At the confluence of India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan, West Bengal is one of the hubs for trafficking.

More than 50,000 young women, a quarter of whom are minors, are missing in this state alone, topping national statistics in this area. Most were kidnapped to feed forced labor or prostitution networks.

Zarin (first name changed) was 16 years old and working in a tailoring workshop in Calcutta when her parents told her they were going to get her married.

“I told them no, that I was still too young,” the young woman remembers.

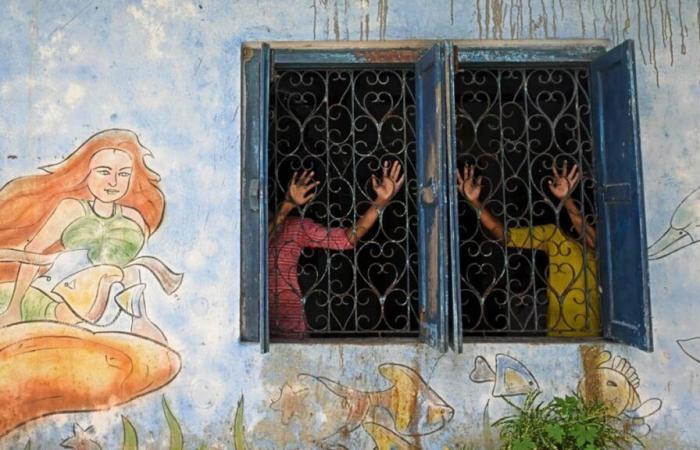

Photo Dibyangshu SARKAR / AFP

Sent by her family to the Kashmir region, she was told, to see her sister, Zarin was then taken in by a man.

It was there that she understood, one day when she had refused to take the meal he was drugging, that she had been sold to a pimp.

“I saw three or four men enter the room,” she describes. “They beat me and sexually assaulted me (…) these memories are still very painful to talk about.”

The young woman, who ended up escaping her “guardians”, believes she was “sold” for around 3,200 euros.

“Lack of support”

The US State Department’s latest annual report on human trafficking noted the “significant progress” made by India in this area, but noted that its eradication was still a very distant goal.

“Traffickers sexually exploit millions of people in India,” notes the report, which describes in particular “arranged marriages in India and in the (Arab-Persian) Gulf countries” to feed the networks.

Among the victims, a “significant number” of Nepalese and Bangladeshi women lured by false promises of employment, via social networks or dating applications.

Founder of the NGO Impact Dialogue Foundation, which supports survivors, Pallabi Gosh assures that only a portion of the victims are recorded.

“Once the young woman is saved,” she explains, families often “do not file a complaint (…) for fear of “stigma.” »

Photo Dibyangshu SARKAR / AFP

“Sometimes, relatives cling to the idea that a minor was married into a richer family and that their responsibility is less,” adds Pinaki Sinha, of the anti-trafficking NGO Sanlaap.

Many of these young women, according to these NGOs, are sold in payment of a debt or a loan.

Until last February, Ayesha (first name changed) worked in a clothing workshop in the Bangladeshi capital Dhaka. One day, a woman he met on a bus offered him a better-paid job in India.

In exchange for a sum of 24,000 rupees (260 euros), the young woman was promised a job in a sari factory.

“Forget all that”

“I stole money from my mother and gave it to my friend. I thought I could repay him by working,” she says.

But once he crossed the border, his dream collapsed. She was told that the job she had been promised no longer existed, but that she could make a living dancing in a bar.

Ayesha got scared and wanted to return to Bangladesh. The man who kidnapped her prevented her from doing so.

“I begged him to leave me, I cried (…) He not only abused me and tore off my clothes, he beat me. He told me that I had to obey him otherwise he would hand me over to the police.”

Then another man who introduced himself as a police officer attacked her in turn. “The policeman and the other man raped me eight or nine times in the space of 18 days.”

The young woman finally managed to escape thanks to a neighbor and filed a complaint.

“I told the police I wanted these two men punished,” but they told her it was her fault for trusting the girl.

Ayesha is now determined to turn the page and dreams of becoming a beautician. “I want to be able to be enough for myself and forget all that.”