Santa Ana’s powerful winds sometimes approach hurricane force. Since January 7, 2025, they have been sweeping the mountains outside Los Angeles and pushing the fires into residential neighborhoods.

By January 8, more than 1,000 structures had burned, mostly homes, and at least five people had died. Authorities have urged more than 100,000 residents to evacuate, but winds are so strong that firefighters are struggling to control the flames.

Jon Keeley, research ecologist in California with the US Geological Survey and associate professor at UCLA (University of California at Los Angeles), looks at the causes of these extreme winds in Southern California and explains why they create such fire risks.

What causes Santa Ana winds?

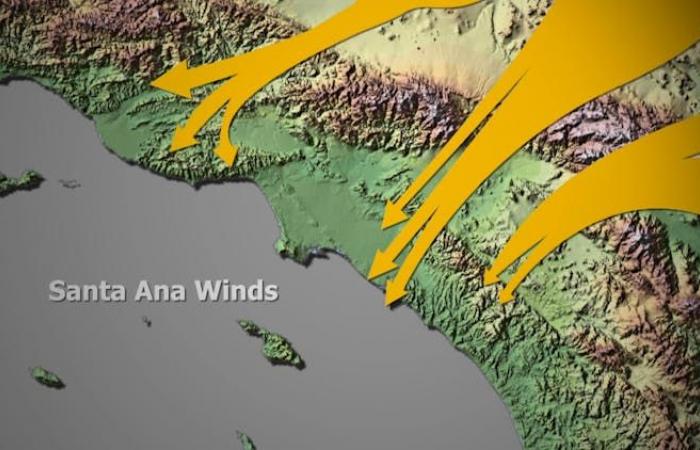

Santa Ana winds are dry, powerful winds that blow down from the mountains toward the coast in Southern California. On average, ten episodes of Santa Ana winds occur each year, usually between fall and January. When conditions are dry, as is currently the case, these winds promote fire risks.

Kmusser, Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

Santa Ana winds occur when high atmospheric pressures are located to the east, in the “Great Basin” (the “Great Basin” is one of the deserts of the American West that extends from the Sierra Nevadas to California, across Nevada in particular), and that a low pressure system sets up off the Californian coast. Air masses move from the anticyclone (high pressure) to the depression (low pressure) – and the wind blows the faster the greater the pressure difference.

Topography also plays a role: As winds descend from the tops of the San Gabriel Mountains, they become even drier and even hotter – a property of air mass physics. So much so that when the winds reach the location where the Eaton Fire broke out in Altadena on January 7, it is not uncommon for their water vapor content to be below 5% relative humidity ( which gives the ratio between the water vapor content of the air and its maximum capacity to contain it under given conditions). In other words, there is almost no humidity in the air at this point.

USGS

In addition, the winds are channeled by the canyons. During Santa Ana wind events, the wind is sometimes very strong in some places and completely absent a few blocks away – an impressive phenomenon that I witnessed when I lived in the Altadena area.

These strong, dry winds typically reach speeds of 30 to 40 miles per hour (on the order of 50 to 65 kilometers per hour), but they can also be faster. Thus, at the beginning of January 2025, they would have reached 60 to 70 miles per hour, or between 100 and 115 kilometers per hour.

Why was the fire risk so high this time?

Typically, during the Santa Ana wind season, Southern California received enough rain that vegetation was moist and did not burn easily, and a study a few years ago showed that fall humidity reduces the risk of fires caused by Santa Ana winds.

-This year, however, Southern California is extremely dry. The vegetation has received very little bad weather in recent months. This drought, combined with extreme winds, provides an ideal breeding ground for major fires.

AP Photo/Richard Vogel

It is very difficult to put out a fire in these conditions. The firefighters of the region can testify to this: during a fire fueled by the Santa Ana winds, they evacuate the populations located in front of the fire front and try to control its flanks, but they have very little chance of stop the fire until the wind subsides.

Other US states have experienced similar fires caused by strong downslope winds. During the “Chimney Tops 2” fire in Tennessee in November 2016, strong downslope winds spread flames into homes in Gatlinburg, killing 14 people and burning more than 2,500 homes. In December 2021, around 1,000 homes in Boulder County, Colorado burned when powerful winds coming down from the mountains spread the Marshall Fire.

Have the Santa Ana winds changed over time?

Santa Ana winds are nothing new, but they are becoming more common this time of year. My colleagues and I recently published a paper comparing 71 years of Santa Ana winds since 1948. We found that overall Santa Ana wind activity remained roughly similar, but their timing was changing: less than events in September and more in December and January. Given the well-documented trends in climate change, it is tempting to attribute this development to global warming, but there is currently no substantial evidence regarding the Santa Ana winds in particular.

That said, it is clear that California is experiencing more destructive fires than in the past. This phenomenon is not only due to climate changes and winds, but also to demographic changes in the region.

Indeed, a growing number of inhabitants today live in wild areas or on their outskirts. The power grid has grown to accommodate these demographic changes, and this increases the potential for wildfires to start because power lines are vulnerable during extreme weather events. By falling or being hit by tree branches for example, they can cause fires. As a result, the areas affected by power line fires are expanding considerably, and today power line accidents are the leading cause of fires in Southern California.

AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes

The Eaton Fire is spreading through an area at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains that was far less populated just fifty years ago. Parts of this San Gabriel basin were then surrounded by citrus orchards, and fires that broke out in the mountains burned in the orchards before reaching homes.

Today, this buffer zone between homes and nature has disappeared. The fire that ravaged Altadena seems to have started from one of these relatively new neighborhoods, or from its surroundings. Houses are built of dry materials that burn easily when the atmosphere is dry. This allows fires to spread quickly and increases the risk of megafires.