In his workshop in the Afghan city of Herat, Sakhi has made rubabs, an iconic Central Asian stringed instrument, for decades. And even if the Taliban want to silence the Music, he stands firm.

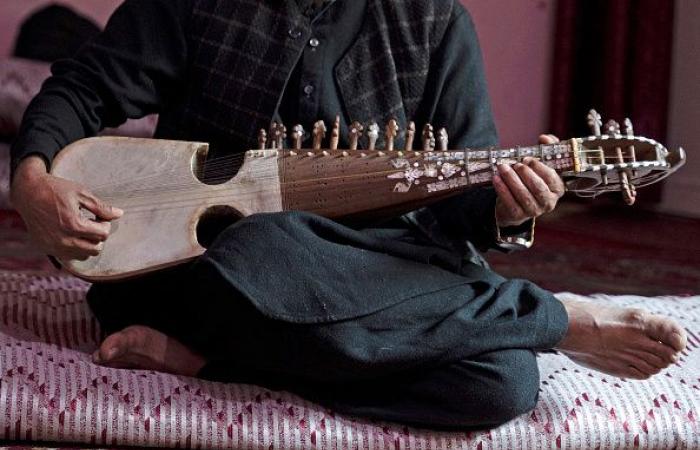

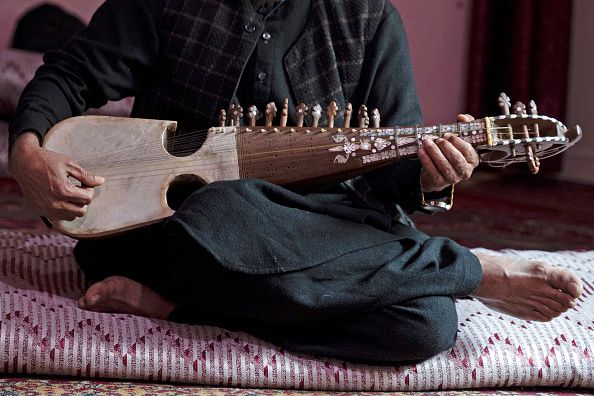

“This job is the only one I know how to do and I have to earn money one way or another,” says the 54-year-old craftsman, sitting on the floor of his tiny workshop where four rubabs, an instrument of the lute family, are being fine-tuned.

But beyond the income he hopes to make from it, there is “the cultural value” that the object represents, says Sakhi, whose first name, like that of the other people interviewed, has been changed for security reasons.

“The value of this work, for me, is the heritage that it embodies,” he explains to AFP, wishing that “this heritage will not be lost.”

Registration as UNESCO intangible cultural heritage

Unesco agrees: in December the UN organization included in its list of intangible cultural heritage the art of making and practicing rubab in Afghanistan, Iran, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

An instrument made from dried mulberry wood collected in deserts, sometimes inlaid with mother-of-pearl, the rubab is one of the oldest musical instruments in Central Asia, played during many celebrations. But in Afghanistan, this sound has almost disappeared since the Taliban returned to power in August 2021.

Instruments were smashed or burned

Their rigorous interpretation of Islamic law almost completely prohibits music: it is no longer played in concerts, nor on the radio or television and very rarely in cars.

Music schools closed and instruments were smashed or burned, as were loudspeakers.

Many musicians have left the countrys

Over the past three years, many musicians have left the country.

His instrument broken by the Taliban

The Taliban have encouraged those who remain to fall back on declaiming religious songs or poetry, as they did during their previous reign (1996-2001).

Gull Agha, 40, keeps a photograph from this period on his phone: his music teacher reveals, full of chagrin, his instrument broken by the Taliban. He himself saw his people being ransacked.

“Transmitting local music to future generations”

And if he’s been made to promise to stop playing, he sometimes slides his fingers over the strings for a few tourists visiting Herat – a city once known for its art and music scene – while complaining about disagreements.

“What motivates me the most is to bring something to Afghanistan, we should not let our country’s know-how be forgotten,” he says. “It is our duty to pass on local music to future generations as our ancestors did.”

“Unfortunately joy has been taken from this nation”

“Rubab is an art and art brings peace to the soul,” he philosophizes. Mohsen, a longtime member of a musicians’ association, chokes back tears as he recalls the time when they represented “the beautiful moments in people’s lives.”

“Unfortunately, joy has been taken from this nation,” he laments, while wanting to keep a glimmer of hope.

“So that music survives”

“Today, people do not play to make money but to (secretly) bring joy to others and for music to survive,” he says, assuring that “no one can silence this sound.”

In Kabul, Majid hasn’t touched a rubab for three years for fear of being heard, after spending years giving concerts.

Touching his instrument for the first time in front of the AFP, a smile appeared on his face before he jumped when he heard the garden gate slam, fearing a Taliban raid.

The long handle of his “dear rubab” was broken when the morality police searched his house after the return of the Taliban, he told AFP. He repaired it as best he could.

“As long as I live I will keep him with me”

“As long as I live I will keep it with me and I hope that my children will too, so the rubab culture will not be lost,” he says.

“Music never disappears. As they say, ‘there can be no death without tears and no marriage without music’. »

How can you help us stay informed?

Epoch Times is a free and independent media outlet, receiving no public support and not belonging to any political party or financial group. Since our creation, we have faced unfair attacks to silence our information, particularly on human rights issues in China. This is why we are counting on your support to defend our independent journalism and to continue, thanks to you, to make the truth known.